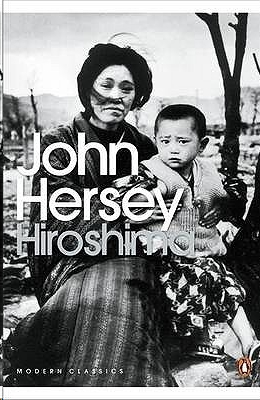

Hiroshima

Authors: John Hersey

First published in the

NEW YORKER

, August, 1946

Published in Penguin Books

November 1946

Made and printed in Great Britain

for Penguin Books Ltd. by C. Nicholls and Co. Ltd.

London, Manchester, Reading

ON Monday, August 6th, 1945, a new era in human history opened. After years of intensive research and experiment, conducted in their later stages mainly in America, by scientists of many nationalities, Japanese among them, the forces which hold together the constituent particles of the atom had at last been harnessed to man’s use: and on that day man used them. By a decision of the American military authorities, made, it is said, in defiance of the protests of many of the scientists who had worked on the project, an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. As a direct result, some 60,000 Japanese men, women and children were killed, and 100,000 injured; and almost the whole of a great seaport, a city of 250,000 people, was destroyed by blast or by fire. As an indirect result, a few days later, Japan acknowledged defeat, and the Second World War came to an end.

For many months little exact and reliable news about the details of the destruction wrought by the first atomic bomb reached Western readers. Millions of words were written, in Europe and America, explaining the marvellous new powers that science had placed in men’s hands; describing the researches and experiments that had led up to this greatest of all disclosures of Nature’s secrets: discussing the problems for man’s future which the new weapon raised. Argument waxed furious as to the ethics of the bomb: should the Japanese have received advance warning of America’s intention to use it? Should a demonstration bomb have been exploded in the presence of enemy observers in some remote spot where it would do a minimum of damage, as a warning to the Japanese people, before its first serious use? But of the feelings and reactions of the people of Hiroshima to the bomb, nothing, or at least nothing that was not pure imagination, could be written; for nothing was known.

In May, 1946,

The New Yorker

sent John Hersey, journalist and author of

A Bell for Adano

, to the Far East to find out what had really happened at Hiroshima: to interview survivors of the catastrophe, to endeavour to describe what they had seen and felt and thought, what the destruction of their city, their lives and homes and hopes and friends, had meant to them in short, the cost of the bomb in terms of human suffering and reaction to suffering. He stayed in Japan for a month, gathering his own material with little, if any, help from the occupying authorities; he obtained the stories from actual witnesses. The characters in his account are living individuals, not composite types. The story is their own story, told as far as possible in their own words. On August 31st, 1946, Hersey’s story was made public. For the first time in

The New Yorker

’s career an issue appeared which, within the familiar covers, bearing—for such covers are prepared long in advance—a picnic scene, carried no satire, no cartoons, no fiction, no verse or smart quips or shopping notes: nothing but its advertisement matter and Hersey’s 30,000-word story.

That story is built round the experiences of six people who were in Hiroshima when the bomb dropped, each of whom, by some strange chance, escaped, not unscathed, but at least with life. One, a Roman Catholic missionary priest, was a German; the other five were Japanese: a Red Cross hospital doctor, another doctor with a private practice, an office girl, a Protestant clergyman, and a tailor’s widow. For some time after the bomb had fallen, none of them knew exactly what had happened: they hardly realised that their old familiar life had ended, that they had been chosen by chance, or destiny, or—as two of them at any rate would have put it—by God, to be helpless small-part actors in an unparalleled tragedy. Bit by bit came the awakening to the magnitude of the calamity that had removed, in a flash, nearly all their accustomed world.

Hersey’s vivid yet matter-of-fact story tells what the bomb did to each of these six people, through the hours and the days that followed its impact on their lives. It is written soberly, with no attempt whatever to “pile on the agony”—the presentation at times is almost cold in its economy of words. To six ordinary men and women, at the time and afterwards, it seemed—like this.

The New Yorker’s

original intention was to make the story a serial. But in an inspired moment, the paper’s editors saw that it must be published as a single whole and decided to devote a whole issue to Hersey’s masterpiece of reconstruction. For ten days Hersey feverishly rewrote and polished his story, handing it out by instalments to the printers, and no hint of what was in the air escaped from

The New Yorker

office. On August 31st, in the paper’s usual format, the historic issue appeared. It created a first-order sensation in American journalistic history: a few hours after publication the issue was sold out. Applications poured in for permission to serialise the story in other American journals, among them the New York

Herald Tribune

, Washington

Post

, Chicago

Sun

, and Boston

Globe

. A condensed version—the cuts personally approved by Hersey—was broadcast in four instalments by the American Broadcasting Company. Some fifty newspapers in the U.S. eventually obtained permission to use the story in serial form, the copyright fees, after tax deduction, at Hersey’s direction going to the American Red Cross. Albert Einstein ordered a thousand copies of the

New Yorker

containing the story. Even stage rights were sought from the author, though he refused to give permission for dramatisation. British newspapers and press syndicates immediately cabled for reproduction rights: but the

New Yorker’s

executives insisted that no cutting could be permitted, and with British paper rationing, full newspaper publication was seen to be impracticable. The book production rights for the United States were secured by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and the American Book of the Month Club chose it for publication as an “Extra”; and the B.B.C. obtained permission to broadcast the article in full in four episodes as part of their new Third Programme.

Penguin Books

, feeling that Hersey’s story should receive the widest possible circulation in Great Britain, immediately cabled to Alfred A. Knopf for, and were accorded, permission to issue it complete in book form. It here appears save for following English spelling conventions in an edition of 250,000 copies, exactly as it appeared in the pages of the

New Yorker

. Many accounts have been published telling—so far as security considerations allow—

how

the atom bomb works. But here, for the first time, is not a description of scientific triumphs, of intricate machines, new elements, and mathematical formulas, but an account of

what

the bomb does—seen through the eyes of some of those to whom it did it: of those who endured one of the world’s most catastrophic experiences, and lived.

The following note appeared in the

NEW YORKER

of 31 August, 1946, as an introduction to John Hersey’s article

The NEW YORKER this week devotes its entire editorial space to an article on the almost complete obliteration of a city by one atomic bomb, and what happened to the people of that city. It does so in the conviction that few of us have yet comprehended the all but incredible destructive power of this weapon, and that everyone might well take time to consider the terrible implications of its use.

A NOISELESS FLASH

AT exactly fifteen minutes past eight in the morning, on August 6, 1945, Japanese time, at the moment when the atomic bomb flashed above Hiroshima, Miss Toshiko Sasaki, a clerk in the personnel department of the East Asia Tin Works, had just sat down at her place in the plant office and was turning her head to speak to the girl at the next desk. At that same moment, Dr. Masakazu Fujii was settling down cross-legged to read the Osaka

Asahi

on the porch of his private hospital, overhanging one of the seven deltaic rivers which divide Hiroshima; Mrs. Hatsuyo Nakamura, a tailor’s widow, stood by the window of her kitchen, watching a neighbour tearing down his house because it lay in the path of an air-raid-defence fire lane; Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge, a German priest of the Society of Jesus, reclined in his underwear on a cot on the top floor of his order’s three-story mission house, reading a Jesuit magazine,

Stimmen der Zeit

; Dr. Terufumi Sasaki, a young member of the surgical staff of the city’s large, modern Red Cross Hospital, walked along one of the hospital corridors with a blood specimen for a Wassermann test in his hand; and the Reverend Mr. Kiyoshi Tanimoto, pastor of the Hiroshima Methodist Church, paused at the door of a rich man’s house in Koi, the city’s western suburb, and prepared to unload a handcart full of things he had evacuated from town in fear of the massive B-29 raid which everyone expected Hiroshima to suffer. A hundred thousand people were killed by the atomic bomb, and these six were among the survivors. They still wonder why they lived when so many others died. Each of them counts many small items of chance or volition—a step taken in time, a decision to go indoors, catching one street-car instead of the next—that spared him. And now each knows that in the act of survival he lived a dozen lives and saw more death than he ever thought he would see. At the time, none of them knew anything.

The Reverend Mr. Tanimoto got up at five o’clock that morning. He was alone in the parsonage, because for some time his wife had been commuting with their year-old baby to spend nights with a friend in Ushida, a suburb to the north. Of all the important cities of Japan, only two, Kyoto and Hiroshima, had not been visited in strength by

B-san

, or Mr. B, as the Japanese, with a mixture of respect and unhappy familiarity, called the B-29; and Mr. Tanimoto, like all his neighbours and friends, was almost sick with anxiety. He had heard uncomfortably detailed accounts of mass raids on Kure, Iwakuni, Tokuyama, and other nearby towns; he was sure Hiroshima’s turn would come soon. He had slept badly the night before, because there had been several air-raid warnings. Hiroshima had been getting such warnings almost every night for weeks, for at that time the B-29s were using Lake Biwa, northeast of Hiroshima, as a rendezvous point, and no matter what city the Americans planned to hit, the Super-fortresses streamed in over the coast near Hiroshima. The frequency of the warnings and the continued abstinence of Mr. B with respect to Hiroshima had made its citizens jittery; a rumor was going around that the Americans were saving something special for the city.

Mr. Tanimoto is a small man, quick to talk, laugh, and cry. He wears his black hair parted in the middle and rather long; the prominence of the frontal bones just above his eyebrows and the smallness of his moustache, mouth, and chin give him a strange, old-young look, boyish and yet wise, weak and yet fiery. He moves nervously and fast, but with a restraint which suggests that he is a cautious, thoughtful man. He showed, indeed, just those qualities in the uneasy days before the bomb fell. Besides having his wife spend the nights in Ushida, Mr. Tanimoto had been carrying all the portable things from his church, in the close-packed residential district called Nagaragawa, to a house that belonged to a rayon manufacturer in Koi, two miles from the centre of town. The rayon man, a Mr. Matsui, had opened his then unoccupied estate to a large number of his friends and acquaintances, so that they might evacuate whatever they wished to a safe distance from the probable target area. Mr. Tanimoto had had no difficulty in moving chairs, hymnals, Bibles, altar gear, and church records by pushcart himself, but the organ console and an upright piano required some aid. A friend of his named Matsuo had, the day before, helped him get the piano out to Koi; in return, he had promised this day to assist Mr. Matsuo in hauling out a daughter’s belongings. That is why he had risen so early.

Mr. Tanimoto cooked his own breakfast. He felt awfully tired. The effort of moving the piano the day before, a sleepless night, weeks of worry and unbalanced diet, the cares of his parish—all combined to make him feel hardly adequate to the new day’s work. There was another thing, too: Mr. Tanimoto had studied theology at Emory College, in Atlanta, Georgia; he had graduated in 1940; he spoke excellent English; he dressed in American clothes; he had corresponded with many American friends right up to the time the war began; and among a people obsessed with a fear of being spied upon—perhaps almost obsessed himself—he found himself growing increasingly uneasy. The police had questioned him several times, and just a few days before, he had heard that an influential acquaintance, a Mr. Tanaka, a retired officer of the Toyo Kisen Kaisha steamship line, an anti-Christian, a man famous in Hiroshima for his showy philanthropies and notorious for his personal tyrannies, had been telling people that Tanimoto should not be trusted. In compensation, to show himself publicly a good Japanese, Mr. Tanimoto had taken on the chairmanship of his local

tonarigumi

, or Neighbourhood Association, and to his other duties and concerns this position had added the business of organising air-raid defence for about twenty families.