History of the Second World War (108 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

Iwo Jima, being regarded as the easier operation, was to be tackled first. Moreover it was wanted as an emergency landing place for the B.29 Superfortresses which had been bombing Tokyo from the Marianas since late November, and as a base for the fighter planes escorting them — as no fighters could fly the entire distance.

A volcanic island, only four miles long, Iwo was uninhabited except for its garrison. This had not been large until September, and could not have offered much resistance, but since then the garrison had been increased to some 25,000 men, and General Kuribayashi had developed the defences into a network of excavated caves, well-concealed and connected by deep tunnels. His aim was simply to hold out as long as possible, as there could be no later reinforcement because of the Americans’ huge naval-air superiority, and he relied on the sheer defensive strength of his position, eschewing costly and characteristic Japanese counterattacks.

The attack on Iwo Jima was entrusted by Nimitz to Admiral Raymond Spruance, who took over command of the 3rd Fleet from Halsey in the last week of January, 1945 — it was now for the time being renamed the 5th Fleet — and for the land part of the operation he was given three Marine divisions. The preparatory air and sea bombardment was the most prolonged hitherto in the Pacific war, with daily air strikes from December 8 on, day and night bombing from January 3 on, and a final three days of intense naval bombardment. But all this had disappointingly little effect on the deeply fortified Japanese defences. When the Marines landed on the morning of February 19, they were met with intense mortar and artillery fire, and for a long time were pinned down on the beaches, suffering 2,500 casualties on that first day out of 30,000 men who were landed.

In the days that followed the Marines slowly fought their way forward, almost yard by yard, with abundant and constant fire-support from air and sea, which was increased when Mitscher’s fast carriers were brought back to reinforce, after their great raid on Tokyo. Not until March 26 was the conquest of the island achieved, after over five weeks’ bitter fighting, and by then the Marine battle losses had risen to about 26,000 — 30 per cent of the entire landing force. The Japanese had fought so stubbornly that 21,000 had been killed, and barely 200 taken prisoner. The mopping up of pockets continued for more than two months longer, bringing the total of Japanese killed up to over 25,000, while only a thousand were taken prisoner. Before the end of March three airfields were ready for the American planes, and by the end of the war some 2,400 landings by B.29 bombers had been made there.

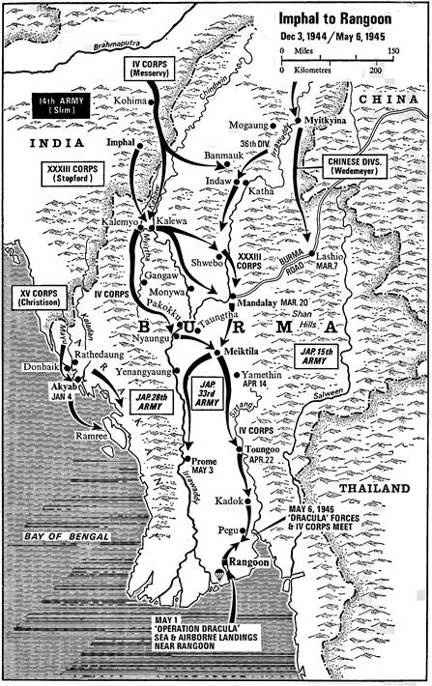

THE BURMA CAMPAIGN — FROM IMPHAL TO THE RECAPTURE OF RANGOON, IN MAY 1945

Although the repulse, at Imphal, of the Japanese offensive in the spring of 1944 was a severe setback, it was not crushing enough to break their hold on Burma. That depended on whether it could be followed up effectively, and for this purpose the British supply system had to be more fully developed.

The task that Mountbatten was set by the Combined Chiefs of Staff directive of June 3 was to broaden the air-link to China and exploit the development of a land-route, with the forces already allotted to him. Although not specifically mentioned, the reconquest of Burma was expected. The two main plans considered were ‘Capital’, an overland thrust to recapture north-central Burma, and ‘Dracula’, an amphibious one to take southern Burma. The latter had the prospect of greater effect, but it depended on outside supplies. In the circumstances General Slim and the Americans preferred the overland plan. So, although preparation for both plans was ordered, the emphasis was on ‘Capital’.*

* See also map on p. 514.

Despite the great improvement of communications from India, and India’s development as a major base, it became evident that much more had to be done if an invasion of Burma was to be really, and speedily, effective. Basically, the main problems were logistical, rather than tactical. Notwithstanding the improvement of land communications and inland water transport, the dependence of Slim’s Fourteenth Army on air supply remained, and that in turn depended on adequate aid from American cargo aircraft.

Thus the second half of 1944 became primarily devoted to such development, and to reorganisation in the commands. Among the more significant features, the air supply system was put under an integrated H.Q. called Combat Cargo Task Force, the Intelligence services were co-ordinated, and the ‘Special Force’ units disbanded. Reorganisation was facilitated when, in October, Stilwell was recalled from China at the insistence of Chiang Kai-Shek, with whom he had been increasingly at loggerheads. General A. C. Wedemeyer replaced him as Chief of Staff to Chiang Kai-Shek and the Chinese forces. In November General Sir Oliver Leese, who had been commanding the Eighth Army in Italy, was sent out to be C.-in-C. Allied Land Forces, South-East Asia, under Mountbatten.

In mid-October, when the monsoon rains ceased and the ground dried, Slim began the advance on the central front, ‘Operation Capital’, concentrating Stopford’s 33rd Corps forward, at the southern end of the Kabaw valley, to capture Kalemyo and Kalewa (130 miles south of Imphal), establishing a bridgehead across the Chindwin near Kalewa by mid-December, and then, reinforced by the 4th Corps (now under General Messervy), exploiting south-eastward to Monywa and Mandalay (160 miles beyond Kalewa).

On the other side, the Japanese High Command, facing the greater and near-approaching menace of the American seaborne advance to the Philippines, could spare no reinforcements for General Kimura’s Burma Area Army — although telling Kimura that he must hold his ground in order to prevent the Allies opening the Burma Road, or moving on Malaya. The Japanese prospects of fulfilling these defensive tasks were poor, with their strength badly diminished by their own protracted Imphal offensive. On the Central Front four understrength divisions of the Japanese 15th Army, amounting to a total of merely 21,000 troops, faced a possible eight or nine strong divisions, and the only reinforcement could come from the division in south Burma — the use of which would mean uncovering Rangoon. Although some of Slim’s forces were being held back for the projected ‘Operation Dracula’, he could count on having a superior number of divisions, all of larger strength, much stronger armoured support, and clear command of the air. Reckoning with these hard facts, the Japanese recognised that they might have to withdraw from northern Burma, but still hoped to hold a line covering Mandalay and the Yenangyaung oilfields (140 miles to the south, down the Irrawaddy River).

While the British offensive on the Central Front was developing, operations in the two subsidiary areas of Arakan and northern Burma reached a successful conclusion.

The objective of Christison’s 15th Corps, as soon as the monsoon ceased, was to clear Arakan, seize Akyab Island for its air bases, and then release troops for the main campaign. For his task Christison had three strong divisions against the two weak divisions of Sakurai’s so-called 28th Army. The British advance began on December 11, and quickly took Donbaik at the tip of the peninsula, on the 23rd, and Rathedaung on the cast bank of the Mayu River a week later, while the third of Christison’s divisions was clearing the Kaladan valley, farther inland. The lack of opposition was due to the fact that the Japanese were in the process of withdrawing from Arakan. This prompted an acceleration of the plans to take Akyab — which was found abandoned when the British occupied it on January 4.

The need for further air bases led Christison to plan the capture of Ramree Island, seventy miles farther south, and this was easily secured on the 21st — as the Japanese were now mainly concerned to hold the passes across the mountains to the lower Irrawaddy, and prevent the British breaking into central Burma. Indeed the credit of the campaign largely went to the small Japanese rearguards who held on to the approaches, and the passes, until the end of April, thus enabling Sakurai’s depleted army to extricate itself from Arakan. Their tenacious defence was helped, however, by the fact that Christison’s corps was now more concerned in planning for ‘Dracula’, for which a large part of its forces had already been withdrawn.

In China itself the campaign had gone badly for Chiang Kai-Shek’s forces during 1944, and that had led to a reversal of the Trident Conference’s decision on the priorities for air supplies over the ‘Hump’, the emphasis now being given to building up the Chinese armies rather than the American strategic air forces in China. Even in the westerly province of Yunnan, an offensive by twelve Chinese divisions was checked by a single Japanese division, although this was outnumbered 7 to 1.

On the northern front in Burma, Stilwell’s forces, mostly Chinese, had made little progress during the spring against the three weak divisions of Honda’s 33rd Army, in their effort to advance through Myitkyina against the northern flank of the Burma Road. There was an improvement in the autumn, however, after the exhausted Chindits had been replaced by the 36th Indian/British Division, and also, ironically, after the majority of the Chinese divisions had been withdrawn to meet the Japanese offensive in China. A further improvement followed Stilwell’s replacement by Wedemeyer, and under him the take-over of the N.C.A.C. (Northern Combat Area Command) by General Sultan, another fresh American commander.

In December Sultan’s forces, and not least its two remaining Chinese divisions, made quicker progress, and Honda’s weak Japanese divisions were forced to retreat — south-westward, towards Mandalay. By mid-January this west-central stretch of the Burma Road was clear of the Japanese. By April the whole of it, from Mandalay to China, was again open.

By mid-November 1944, Stopford’s 33rd Corps had established a bridgehead over the Chindwin, and Messervy’s 4th Corps then thrust on eastwards into the Shwebo-Mandalay plain — while making contact at Banmauk, north-west of Indaw, with Festing’s 36th Division which had by then pushed as far south as Indaw and Katha, on the Irrawaddy. From the lack of opposition it became evident that the Japanese were withdrawing from the Shwebo plain, thus disappointing Slim’s hope of encircling and crushing them in relatively open country with his superior armour, artillery, and air force, and were falling back to positions on the Irrawaddy near Mandalay. So Slim recast his plan. While Stopford’s 33rd Corps (with the equivalent of four divisions) pressed down on Mandalay from the north to gain crossings there over the Irrawaddy, the 4th Corps (with the equivalent of three divisions) was to advance due south from Kalemyo up the Myittha valley, as stealthily as possible, and then from Gangaw move south-east to gain a crossing over the Lower Irrawaddy near Pakokku, with the aim of creating a strategic barrier near Meiktila across the rear of the Japanese forces holding Mandalay — thus blocking their retreat south to, and supply from, Rangoon. The whole of this encircling plan on the central front depended on the solution of the logistical problems, and especially on adequate air supply.

By the beginning of 1945, while the 4th Corps — was preparing for its deep flanking move, Stopford’s 33rd Corps continued its southward advance on Mandalay. Shwebo was reached and occupied by January 10, Monywa (on the Chindwin) by the 22nd, and another of his divisions had already gained crossings over the Irrawaddy fifty to seventy miles north of Mandalay — making a triple line of advance and threat. Apart from an outlying detachment opposite Mandalay, the Japanese were now all on the east bank of the Irrawaddy.

Slim’s new plan worked almost perfectly. Messervy’s capture of Kahnla near Pakokku on February 10 was the signal for the operation to start. On the 14th his leading division gained a bridgehead near Nyaunga, south of Pakokku, where the Indian Nationalist troops holding that sector were easily overcome. His striking force under General Cowan, the specially motorised 17th Division plus a tank brigade, then passed through and took Taungtha on the 24th, reaching the outskirts of Meiktila on the 28th. It was momentarily cut off when a Japanese detachment reoccupied Taungtha, but was effectively kept supplied by air, and was thus able to capture Meiktila on March 3, after two days’ fighting. Cowan then did his best to keep the initiative, and keep the Japanese confused, by a series of aggressive raids in various directions, by small infantry columns with tanks.

The Japanese were in a perilous situation — hard-pressed around Mandalay and with their rear communications being strangled, as well as being heavily outnumbered on the ground and largely without air cover. Nevertheless they fought back fiercely. Repeated attacks on Fort Dufferin, their stronghold in Mandalay, were repulsed, and they staged a desperate counteroffensive in the Meiktila area to clear their communications, two divisions working up from the south while another was hurried down from Mandalay, all now placed under Honda’s 33rd Army (which had withdrawn from the Northern Front and the Burma Road). During the middle of March this battle was in a critical stage, but by the end of the month the Japanese counteroffensive had been defeated, and was abandoned. Meanwhile Stopford had at last captured Fort Dufferin, and Mandalay, on the 20th. Realising the hopelessness of the situation the Japanese 15th Army had given up its attempt to hold Mandalay and retreated southward. Central Burma was now in British hands, and the way to Rangoon was open. The two British corps had suffered some 10,000 casualties in these weeks of struggle, but the Japanese losses were much higher — amounting probably to a third of their already depleted strength. Worse still for the prospects of further resistance was the loss of equipment they suffered, as they had to retreat eastward into the Shan Hills by a long and circuitous route.