History of the Second World War (41 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

The Japanese invasion of Burma had started as early as mid-December, when a detachment of the 15th Army moved in to Tenasserim, on the western or Burmese side of the Kra Isthmus, to seize the three key airfields there and thus block the way for British air reinforcements to Malaya. On December 23 and 25 heavy Japanese air attacks were delivered on Rangoon, causing the Indian labour force to stream away, blocking the roads and abandoning work on the defences. On January 20 the direct attack opened with an advance from Thailand on Moulmein, which was occupied on the 31st after a stiff but confused struggle — in which the defenders, with the wide Salween River estuary at their backs, had a narrow escape from disaster, and capture.

At the end of December, Wavell had sent his Chief of the General Staff in India, Lieutenant-General T. J. Hutton, to take over the command in Burma, and he in turn had placed the miscellaneous troops defending Moulmein, and the approaches to Rangoon, under Major-General J. G. Smyth, V.C., the commander of the newly arriving 17th Indian Division.

After the fall of Moulmein, the Japanese pressed on north-west, and gained crossings of the Salween near there and some twenty-five miles up-river in the first fortnight of February. Smyth had been urging an adequate strategic withdrawal to a position where he could concentrate, but was not permitted to withdraw until too late to organise such a defence on the Bilin River, itself narrow and fordable at many points. That position was soon turned. Then came a race to get the troops back to the mile-wide Sittang River, thirty miles behind (and seventy from Rangoon). Owing to the delayed start, the Japanese were able to forestall the British, despite the handicap of having to pursue their outflanking moves by jungle tracks, and the vital Sittang Bridge was blown up in the early hours of February 23, leaving most of Smyth’s troops still on the east bank. Barely 3,500 got back, by devious ways, and of these less than half still had their rifles. By March 4 the Japanese, exploiting their advantage, reached and surrounded Pegu, a road and rail junction where the remnants of Smyth’s troops and a few reinforcements were assembling.

The next day, General Sir Harold Alexander arrived to take over the command in Burma from General Hutton. That emergency decision by Churchill was quite natural in the circumstances, and the more so in view of the way that the early collapse had been unforeseen in higher quarters. But it was unjust to ‘Tom’ Hutton who had not only expressed doubt of the possibility of holding Rangoon but shown wise foresight in sending supplies to the Mandalay area 400 miles north of Rangoon, while hastening the construction of a mountain road from the State of Manipur, in India, as an overland link with Mandalay and the Burma Road to Chungking. During this period, and earlier, views at home were much influenced by Wavell’s opinion that Japanese skill was overrated — a myth that could be punctured by vigorous counteraction.

On arrival, Alexander at first insisted that Rangoon must be held and ordered an offensive to restore the situation. But when that was attempted, it gained little, despite vigorous action by the newly-arrived 7th Armoured Brigade and some infantry reinforcements. So Alexander soon came round to accept Hutton’s view, and on the afternoon of March 6 ordered the evacuation of Rangoon, after demolitions carried out the next afternoon. Thus on the 8th the Japanese, to their own surprise, entered a deserted city. Even so, the forces there had luck in escaping, up the road northward through Prome, by finding a gap in the Japanese encirclement.

There was now a temporary pause, during which the Japanese were reinforced by two more divisions, the 18th and 56th, as well as two tank regiments, and their air force was doubled — to over 400 planes. The British received far fewer troop reinforcements. In the air their three depleted fighter squadrons and the two of the American Volunteer Group (lent by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek), totalling only forty-four Hurricanes and Tomahawks at the start, had effectively beaten off Japanese air raids on Rangoon, while inflicting disproportionately heavy losses on the attackers. But with the abandonment of Rangoon most of the British were withdrawn to India — where an initial reinforcement of some 150 planes, bombers and fighters, was received from the Middle East by the end of March. The loss of Rangoon had disrupted the early warning system, so that the remaining British planes were unable — as in Malaya earlier — to put up any effective resistance to the Japanese.

Early in April the strengthened Japanese 15th Army moved north up the Irrawaddy, towards Mandalay, in fulfilment of its aim of cutting and closing the Burma Road to China. The British, now amounting to some 60,000, were holding an east-west line 150 miles south of Mandalay — with the aid of the Chinese forces on their eastern flank. But the Japanese boldly moved round their western flank, enveloping its defenders, and capturing the Yenangyaung oilfields in mid-April. General Joseph Stilwell, the American officer who was Chiang-Kai-Shek’s right hand, devised a plan to let the Japanese push up the Sittang River and then trap them by a pincer-move, but his plan was forestalled and distracted by a wider Japanese move, round the eastern flank, towards Lashio on the Burma Road. A rapid reflux took place on that flank, and it soon became clear that neither Lashio nor the use of the supply route to China could be preserved.

So Alexander wisely decided not to make a stand at Mandalay — as the Japanese hoped he would — but to withdraw towards the Indian frontier. The long withdrawal, of more than 200 miles, began on April 26, covered by rearguards, and the Ava bridge over the Irrawaddy was blown up on the 30th — the day before the Japanese flanking advance reached Lashio.

The principal problem now was to reach the Indian frontier, and Assam, before the monsoon began in mid-May and flooded the intervening rivers as well as the roads. The Japanese raced up the Chindwin River to intercept the British retreat, but the British rearguards managed to get through, by a deviation, and reached Tamu a week before the monsoon began. They lost much of their equipment in the final scurry, including all their tanks, but most of the troops were saved. Even so, their casualties in the Burma campaign had amounted to three times those of the Japanese — 13,500 against 4,500. That the forces in Burma got away at all, in their thousand-mile retreat, was largely due to the repeated interventions, by counterattack, from the tanks of the 7th Armoured Brigade — and the cool-headed way in which the retreat was handled after the decision to abandon Rangoon.

CEYLON AND THE INDIAN OCEAN

While the Japanese army in Burma was moving on, in a seemingly irresistible way, from Rangoon to Mandalay, the British were also suffering alarm from the entry of the Japanese Navy into the Indian Ocean. For the great island of Ceylon, off the south-east corner of India, was considered vital by the British — as a potential springboard for the Japanese Navy from which it could threaten Britain’s troop and supply route to the Middle East round the Cape of Good Hope, and South Africa, as well as her sea-routes to India and Australia. Rubber from Ceylon, too, had become very important to Britain since the loss of Malaya.

Wavell was told by the British Chiefs of Staff that the preservation of Ceylon was more essential than that of Calcutta. For that reason, no less than six brigades were employed to hold Ceylon at a time when the forces in Burma were palpably inadequate and those in India perilously weak. Moreover a fresh naval force was also built up there in March, under command of Admiral Sir James Somerville — which comprised five battleships (although four of these were old and obsolete), and three carriers, one of which (the

Hermes

) was both old and small.

At the same time the Japanese were preparing an offensive move from Celebes into the Indian Ocean with a more powerful force, comprising five fleet carriers — those used in the Pearl Harbor attack — and four battleships. Thus the prospects of preserving Ceylon looked poor when that news came. But the threat was not so serious, nor so substantial as it appeared. For the Japanese naval offensive was basically defensive in aim. They had not the troops available to carry out an invasion of Ceylon. Their aim was a raid — to disperse the British naval force that was being built up there, and to cover their own troop reinforcements that were on the way to Rangoon by sea.

Expecting attack on April 1, Somerville’s force had been divided into two parts — the faster and more effective part, Force A, being on patrol until it was sent to refuel at Addu Atoll, a new secret base in the Maldive Islands some 600 miles south-west of Ceylon. The Japanese stroke actually came on April 5, when over a hundred planes attacked the harbour at Colombo, inflicting much damage and repelling the air counterattacks. A further attack came in the afternoon, from fifty bombers, which sank two British cruisers. Somerville’s two-part force, too late to intervene, then retreated — the older battleships to East Africa, and the faster part to Bombay. But after a successful stroke at Trincomalee on the 9th, the Japanese fleet withdrew, its commerce raiding detachment having meanwhile sunk twenty-three ships (112,000 tons) in the Bay of Bengal during this brief raid.

It was another humiliating defeat for British seapower, but fortunately went no further. Indeed, if the British had not provoked such a stroke by trying to build up a naval force in Ceylon of a palpably obsolescent kind, the Japanese would probably not have attacked — as it was beyond their designed limits.

Another sequel, imposing renewed strain on Britain’s relations with the French as well as diversion of force, was the despatch of a combined army and naval force to seize the harbour of Diego Suarez in the north of French-owned Madagascar — to forestall any possibility of the Japanese occupying it. This rather expensive move in May was followed by a larger expedition in September to take over the whole of the island. As in the case of sinking the French fleet at Mers-el-Kebir, the military port of Oran in Algeria in 1940, fear proved in the long term a bad counsellor.

PART V - THE TURN - 1942

CHAPTER 18 - THE TIDE TURNS IN RUSSIA

In 1940 the Germans had opened their campaign on April 9 with the spring upon Norway and Denmark. In 1941 they had opened it on April 6, with their offensive in the Balkans. But in 1942 there was no such early opening. That fact showed the exhausting effects on the Germans of their frustrated attempt in 1941 to gain a quick victory over Russia, and the extent to which their offensive effort had been absorbed there. For while weather conditions were unfavourable to an early spring move on the Russian front, there was no such hindrance to a move against the eastern or western ends of Britain’s precarious position in the Mediterranean. Yet no fresh threat was developed in this key area of British oversea communications.

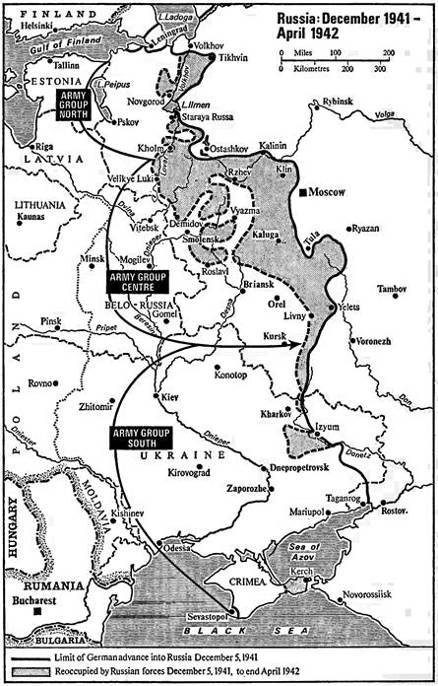

In the Russian theatre, the Red Army’s winter counteroffensive continued for over three months after its December launching, though with diminishing progress. By March it had advanced more than 150 miles in some sectors. But the Germans maintained their hold on the main bastions of their winter front — such towns as Schlusselburg, Novgorod, Rzhev, Vyasma, Briansk, Orel, Kursk, Kharkov, and Taganrog — despite the fact that the Russians were many miles in rear of most of these places, through pushing into the spaces between them.

These bastion-towns were formidable obstacles from a tactical point of view; strategically, they tended to dominate the situation, because they were focal points in the sparse web of communications. While their German garrisons could not prevent infiltration into the wide spaces between them, these communication-blocks cramped and curtailed the exploitation of any penetration so long as they remained intact. Thus they fulfilled, on a larger scale, the braking function which the French forts of the Maginot Line had been designed to perform — and might have succeeded in performing if the chains of forts along the French frontier had not ended at a half-way point which allowed the Germans ample room to outflank it.

As the Red Army failed to undercut these bastions sufficiently to cause their collapse, the deep advances it made in the intervening spaces tended to turn out to its own disadvantage later. For the bulges it made were naturally less defensible than bastion-towns, and thus absorbed an excessive quantity of troops in holding them, while they could more easily be cut off by flanking strokes from the German-held bastions, used as offensive springboards.

By the spring of 1942 the battlefront in Russia had become so deeply indented as to appear almost like a reproduction of Norway’s coastline, with its fiords penetrating far inland. The way that the Germans had been able to hold on to the ‘peninsulas’ was remarkable evidence of the power of modern defence when skilfully and tenaciously conducted, and provided with adequate weapons. It was a lesson that went even beyond the Russian defence of 1941 in refuting the superficial deductions drawn from the swift offensive successes earlier in the war against soft opposition — from cases where the attacker had a decisive superiority in weapon-power or encountered an ill-trained and badly bewildered defence. It repeated on a much larger scale the experiences of the St. Mihiel salient in the First World War, and proved the possibilities that were foreshadowed by the four-years-long maintenance of that theoretically untenable projection. The experience of the 1941 winter campaign also tended to confirm the longer-view evidence of history that the effect of co-incidence is primarily psychological, and that the danger is greatest in the early stages — diminishing if the sudden shock of its realisation, by the partially encircled troops, does not produce an immediate collapse.