Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (7 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

When von Kleist's Panzer Group had succeeded in breaking through east of Lvov and the vehicles with the white 'K' were about to mount their Blitzkrieg offensive, Kirponos instantly blocked the development of large-scale operations and the encirclement of Soviet forces. With armoured units rapidly brought up he launched strong counter-attacks and struck heavily at the spearheads of the advancing German divisions.

He sent his heavy KV-1 and KV-2 tanks into action, as well as the super-heavy Voroshilov model with its five revolving turrets. Against these the German Mark III with its 3.7- or 5-cm. gun was pretty helpless and forced to retreat. Anti-aircraft guns and artillery had to be brought up to fight the enemy armour. But the most dangerous of all

was the Soviet T-34—an armoured giant of great speed and manoeuvrability. It was 19 feet long, 10 feet wide, and 8 feet high. It had wide tracks, a massive turret with outward-sloping sides, it weighed 26 tons, and it carried a 7-62-cm. gun. It was near the Styr that the rifle brigade of 16th Panzer Division encountered the first of them.

The Panzerjäger unit of 16th Panzer Division hurriedly brought up its 3.7 anti-tank gun. Position! Range 100 yards. The Russian tank continued to advance. Fire! A hit. And another hit. And more hits. The men counted them: 21,

22,

23 times the 3-7-cm. shells smacked against the steel colossus. But the shells merely bounced off. The gunners were screaming with fury. The troop commander was pale with tension. The range was down to 20 yards. "Aim at the turret ring," the second lieutenant commanded.Now they had got him. The tank wheeled about and moved off. The turret ring was damaged and the turret immobilized —but otherwise it was unscathed. The anti-tank gunners drew a deep breath. "Would you believe it?" they were saying. From then onward the T-34 was their great bogy. And their 3'7-cm. anti-tank gun, which had rendered such good account of itself in the past, was henceforward nicknamed contemptuously "the army's door- knocker."

Major-General Hube, OC 16th Panzer Division, described the developments during the first few days of the campaign in the south as "slow but sure progress." But "slow and sure" was not provided for by Operation Barbarossa.

Kirponos's forces in Galicia and the Western Ukraine were likewise to have been defeated speedily by means of crushing battles of encirclement.

On the Rumanian-Russian frontier, where the Eleventh Army under Colonel-General Ritter von Schobert stood, nothing much happened on 22nd June. There was no artillery bombardment and no assault was launched. Apart from slight patrol activity across the river Prut, which formed the frontier here, and a few Russian air-raids, things were fairly peaceful. Hitler's timetable purposely envisaged a delay on this sector; the Soviet forces here were to be driven, at the beginning of July, into a pocket that was being formed in the north.

On that fatal day, therefore, at 0315 hours, the Prut was flowing sluggishly to the south, under its usual blanket of light haze. Major-General Roettig, OC 198th Infantry Division, was lying by the river near the village of Sculeni, with his intelligence officer and an orderly officer, watching the opposite bank. The Russian frontier posts were keeping quiet, until suddenly an explosion rent the air. A patrol of 198th Infantry Division had paddled themselves across the Prut and blown up a Soviet guard tower. That was the only noisy incident on the southern flank of the Eastern Front.

Not until the evening of 22nd June did 198th Infantry Division carry out a reconnaissance in force across the Prut in order to occupy the village of Sculeni, through which the river and the frontier ran. The 305th Infantry Regiment occupied the village and formed a bridgehead. The bridgehead was held against strong enemy pressure during the following days.

Day after day passed. The delays on the northern wing of the Army Group in the area of the Sixth and Seventeenth Armies meant that Schobert's divisions had to wait also. At last, on 1st July, the green light was given. The 198th Infantry Division attacked from its bridgehead. Twenty-four hours later the remaining divisions of XXX Corps followed suit: the 170th Infantry Division, under Major-General Wittke, as well as the Rumanian 13th and 14th Divisions. The other two corps of the Army, LIV and XI Corps, crossed the Prut to the right and left of XXX Corps.

Even though one could hardly have expected the enemy to have been taken entirely by surprise eight days after the start of operations, 170th Division nevertheless succeeded in capturing intact the wooden bridge over the Prut near the village of Tutora. In a bold and cunning action Second Lieutenant Jordan led his platoon swiftly through the antitank defences along the Soviet frontier. The 800-yard-long causeway through the marsh was cleared of the enemy. Soviet posts were overcome in hand-to-hand fighting. In the morning 40 Russians lay dead by their machine-guns at the bridge and in the marsh. But Jordan's platoon paid a heavy price: 24 men killed or wounded.

The offensive of Eleventh Army was gaining momentum. Its direction was towards the north-east, towards the Dniester. But things did not go according to schedule; Schobert was not able to drive a retreating enemy into a trap, but had to content himself with slowly pushing back a strongly resisting enemy.

After ten days of very fierce fighting Rundstedt's armoured divisions had penetrated 60 miles into enemy territory. They were involved with superior forces, compelled to beat back counter-attacks from all sides, and defend themselves from the right and the left, from the front and the rear. A strong enemy was offering stubborn but elastic resistance.

Colonel-General Kirponos succeeded in evading the planned German encirclement north of the Dniester and in taking his troops back, still in an unbroken front, to the strongly fortified Stalin Line to both sides of Mogilev. Rundstedt had therefore not succeeded in achieving the planned large-scale breakthrough. The timetable of Army Group South had been upset. Could the delay be made up?

On the Central Front, on the other hand, all went well. After a swift break-through the armoured and motorized divisions of Hoth's and Guderian's Panzer Groups on the wings of the Army Group advanced rapidly according to plan, right through the startled and badly led armies of the Russian Western Front, and got into position for their large- scale pincer movement. It was here on the Central Front that the decisive action of the entire campaign had been scheduled from the outset: it was to be prepared by some 1600 tanks and to be finally consummated—in collaboration with Fourth Panzer Group under Colonel-General Hoepner, then still operating in the area of Army Group North—by the capture of Moscow. The plan seemed to work. The Panzer divisions were once more giving a demonstration of Blitzkrieg—as in the old days, as in Poland and in the West. At least, that was how things looked from where the armoured spearheads stood. The infantry here, as on the northern sector, had a somewhat different experience. The fortress of Brest-Litovsk was a typical example.

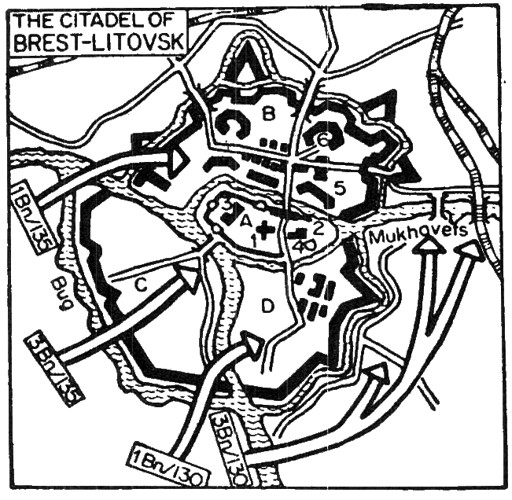

On 22nd June, 45th Infantry Division did not suspect that it would suffer such heavy losses in this ancient frontier fortress. Captain Praxa had prepared his assault against the heart of the citadel of Brest with great caution. The 3rd Battalion, 135th Infantry Regiment, was to take the Western Island and the central area with the barracks block. They had studied it all thoroughly at the sand-table. They had built a model from aerial photographs and old plans from the days of the Polish campaign, when, until it had to be surrendered to the Russians, Brest was in German hands.

Guderian's staff officers realized from the outset that the citadel could be taken only by infantry, since it was proof against tanks.

The circular fortress, occupying an area of nearly two square miles, was surrounded by moats and river branches, and sub-divided internally by canals and artificial watercourses into four small islands. Casemates, snipers' positions, armoured cupolas with anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns, were established, well camouflaged, behind shrubs and under trees. On 22nd June there were in all five Soviet regiments in Brest; these included two artillery regiments, one reconnaissance battalion, an independent anti-aircraft detachment, and supply and medical battalions.

General Karabichev, who was captured beyond the Berezina very early in the campaign, stated under interrogation that in May 1941 he had been instructed, as an expert in fortification engineering, to inspect the western defences. On 8th June he had set out on his trip.

On 3rd June the Soviet Fourth Army had staged a practice alarm. The report on this exercise, which was captured by German units, had this to say about the 204th (Heavy) Howitzer Regiment: "The batteries were not ready to fire until six hours after the alarm." About the 33rd Rifle Regiment it said this: "The duty officers were unacquainted with the alarm regulations. Field kitchens are not functioning. The regiment marches without cover. . . ." About the 246th Anti- Aircraft Detachment it said: "When the alarm was given the duty officer was unable to make a decision." When one has read this report one is no longer surprised at the lack of organized resistance in the town of Brest. But in the citadel proper the Germans got a surprise after all.

When the artillery bombardment began at 0315 hours the 3rd Battalion, 135th Infantry Regiment, was 30 yards from the river Bug, directly opposite the Western Island. The earth trembled. The sky was plunged in fire and smoke.

Everything had been arranged in minute detail with the artillery units which were softening up the citadel: every four minutes the hail of death was to be advanced by 100 yards. It was an accurately planned inferno.

No stone could be left standing after this lot. That, at least, was what the men thought as they lay pressed to the ground by the river. That was what they hoped. For if death did not reap its harvest inside the citadel, then it would surely get them.

After the first four minutes, which seemed like an eternity of thunder, at exactly 0319, the first wave leaped to their

feet. They dragged their rubber dinghies down into the water. They jumped in. And like shadows, veiled by smoke and fumes, they paddled across. The second wave followed at 0323. The men reached the other bank just as if they were on an exercise. Swiftly they climbed the sloping ground. Then they crouched down in the tall grass. Hell above them and hell in front of them. At 0327 Second Lieutenant Wieltsch, commanding No. 1 Platoon, straightened up. The pistol in his right hand was secured by a lanyard so that, if necessary, he had both hands free for the hand-grenades he was carrying in his belt and in two linen bags slung over his shoulders. No word of command was needed. Bent double, they crossed a garden. They moved past fruit-trees and through old stables. They crossed the road which ran along the ramparts. And now they would enter the fortress through the shattered gate-house. But here they had their first surprise. The bombardment, even the heavy shells of the 60-cm. mortars, had done very little damage to the massive masonry of the citadel. All it had done was to waken the garrison and give the alarm. Half dressed, the Russians were scurrying to their posts.

Towards midday the battalions of 135th and 130th Infantry Regiments had forced their way deep into the fortress in one or two places. But at the eastern fort of the Northern Island, as well as by the officers' mess and the barracks block on the Central Island, they had not gained an inch. Soviet snipers and machine-guns in armoured cupolas barred their way. Because of the close interlocking of attacker and defender the German artillery could not intervene. In the afternoon the corps' reserve, 133rd Infantry Regiment, was thrown into the fighting. In vain. A battery of assault guns was brought forward. With their 7-5-cm. guns they blasted the bunkers directly. In vain.

Map 2.

-The citadel of Brest-Litovsk. Attack by the battalions of 130th and 135th Infantry Regiments. A Central Island; B Northern Island; C Western Island; D Southern Island; 1 ancient fortress church; 2 officers' mess; 3 barracks; 4 barracks; 5 strongpoint Fomin; 6 Eastern fort.By evening 21 officers and 290 NCOs and men had been killed. They included Captain Praxa, the battalion commander, and Captain Krauss, commander of 1st Battalion, 99th Artillery Regiment, as well as their combat staffs. Clearly, it could not be done that way. The combat units were pulled back from the fortress, and artillery and bombers had another go. Carefully they avoided the ancient fortress church: there seventy men of the 3rd Battalion sat surrounded, unable to move forward or back. Luckily for them they had a transmitter and had been able to report their position to Division.

Other books

Healing the Bayou by Mary Bernsen

Destiny Redeemed by Gabrielle Bisset

Tomorrow’s Heritage by Juanita Coulson

The Dirigibles of Death by A. Hyatt Verrill

Baby Girl: Dare to Love by Celya Bowers

Gnash by Brian Parker

Mad Moon of Dreams by Brian Lumley

Bones of my Father by J.A. Pitts

Fade Back (A Stepbrother Romance Novella) by Brother, Stephanie

Death Wave by Stephen Coonts