Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (19 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

Thus ends the very first dinosaur battle in literature. The source of Steven Spielberg’s fortune! Passages like this one have kept the novel in print for nearly 150 years, despite the obsolete geological pedagogy threaded throughout.

The geology/paleontology gets increasingly whimsical as the novel progresses, possibly as Verne veered away from the pop science magazine writing he’d done and began warming to the imaginative opportunities his story offered. He still tries to anchor things on a scientific basis, but he can’t resist having some fun. This is especially the case in chapters 37–39, which follow almost immediately after the sea monster battle and were added to the 1867 edition. All three dramatize further developments in paleontology and evolution, but they are played more for their theatrical possibilities than the didactic moments they might provide. Evidently readers really liked the battle of sea monsters, and Verne decided to provide more of the same, whether or not it corresponded to current scientific thinking. Over time, he developed an ability to seamlessly intertwine fact and fantasy.

After the sea monster battle ends, a storm kicks up that sends them flying over the Central Sea for five days. The Professor is delighted; it means major headway. But when the storm abates, they are plopped on the shore right back where they started from. This is where the new material in chapter 37 begins. They decide to explore a bit to get their bearings and come across a “plain, covered with bones. It looked like a huge cemetery … great mounds of bones were piled up row after row, stretching away to the horizon, where they disappeared into the mist. There, within perhaps three square miles, was accumulated the entire history of animal life.” In this welter of remains from all periods—a dreamlike comingling that goes unexplained—the Professor finds a human head. His first reaction is to lord it over the competition stuck on the surface above: “‘Oh, Mr. Milne-Edwards! Oh, Monsieur de Quatrefages! If only you could be standing where I, Otto Lidenbrock, am standing now!” (Both Milne-Edwards and Quatrefages were distinguished professors at the Paris Natural History Museum at the time.) This ends chapter 37.

In chapter 38, Professor Lidenbrock goes a little batso and commences delivering a lecture to the sea of bones, thinking he is addressing a class back in Hamburg. Axel provides a bit of background regarding a discovery (“an event of the highest importance from the paleontological point of view”) near Abbeville, France, on March 28, 1863, of “a human jaw-bone fourteen feet below the surface. It was the first fossil of this sort that had ever been brought to light.” The aforementioned Milne-Edwards and Quatrefages had “demonstrated the incontestable authenticity of the bone in question,” proving it a true human fossil from the Quaternary period. Axel then summarizes the debate that followed, mentioning additional human fossil finds in conclusive strata: “Thus, at one bound, man leapt a long way up the ladder of time; he was shown to be a predecessor of the mastodon … 100,000 years old, since that was the age attributed by the most famous geologists to the Pliocene terrain.”

Amid all the other bones they see “an absolutely recognizable human body, perfectly preserved down the ages.” This is where the Professor flips into lecture mode. “Gentlemen,” he begins, “I have the honor to introduce you to a man of the Quaternary Period.” For the next several pages, he gives a rundown of fossil finds, real and fake, from antiquity down to the present. He next describes the specimen itself—less than six feet tall and “incontestably Caucasian, the white race, our own. This specimen of humanity belongs to the Japhetic race, which is to be found from the Indies to the Atlantic. Don’t smile, gentlemen.” Japhetic is a racial term derived from Japheth, one of Noah’s sons, usually designating the nations of Europe and northern Asia. The phrase “Indies to the Atlantic” is obscure, but then he’s lecturing to an endless boneyard. Given the prevailing racism of the time, it is hardly surprising that this Quaternary Man is a bona fide Caucasian. Verne dodges questions of evolution by making his specimen a modern man. How did he get down there? Once again the Professor relies on the catastrophist principle of a cooling, shrinking earth riddled with “chasms, fissures, and faults.” So maybe the stratum he was buried in just fell through. Or had such people lived here? The chapter ends: “Might not some human being, some native of the abyss, still be roaming these desolate shores?”

In chapter 39, “Man Alive,” Verne tosses in every paleontological element he can think of for a big finish. The three continue walking until they come to “the edge of a huge forest” that turns out to be a botanical garden of trees and plants from all habitats and climates, “the vegetation of the Tertiary Period in all its splendor.” But “there was no colour in all these trees, shrubs, and plants, deprived as they were of the vivifying heat of the sun.” Axel says, “I saw trees from very different countries on the surface of the globe, the oak growing near to the palm, the Australian eucalyptus leaning against the Norwegian fir, the northern birch tree mingling its branches with those of the Dutch Kauris. It was enough to drive to distraction the most ingenious classifiers of terrestrial botany.” As well as the reader, since these trees couldn’t possibly coexist in the same habitat. Verne is trying too hard in these added chapters, straining for effect in a way the original material seldom does.

Out of the blue, they come on a living man—a huge shepherd tending a flock of mastodons. This “Proteus of those subterranean regions, a new son of Neptune,” is twelve feet tall and has a head “as big as a buffalo’s … half hidden in the tangled growth of his unkempt hair … In his hand he was brandishing an enormous bough, a crook worthy of this antediluvian shepherd.” A giant prehistoric hippie! For once the Professor agrees that they should run for it, and they take off so quickly that Axel later questions whether they really saw the apparition. The appearance of the giant shepherd goes unexplained, a brief tableau Verne felt moved to include as a further nod to the interest in ape men, for its sensational quality and not as an integral part of the plot. We glimpse him and he’s gone.

I’m one in a long line of readers who has trouble with the way Verne gets Axel, the Professor, and taciturn Hans back up to the surface. While using their remaining “gun-cotton” (another item they drag along with them and produce at the right moment) to blow up a boulder lodged in their exit passageway, they accidentally use too much force:

The shape of the rocks suddenly changed before my eyes; they opened like a curtain. I caught sight of a bottomless pit which appeared in the very shore. The sea, seized with a fit of giddiness, turned into a single enormous wave, on the ridge of which the raft stood up perpendicularly.

And the roller-coaster ride is on. They’ve blown a hole in this level of the inner earth and the sea goes rushing down into the abyss, carrying them along on the raft. An hour, two hours go by, and still they plunge. “We were moving faster than the fastest of express trains.” Resourceful Hans manages to light a lantern, so they can see what’s happening. They are in a wide gallery, and “the water was falling at an angle steeper than that of the swiftest rapids in America.” Their speed increases and then “a water-spout, a huge liquid column, struck its surface [the raft’s]”—and then they are being propelled upward. The Professor naturally has an explanation: “The water has reached the bottom of the abyss and is now rising to find its own level, taking us with it.” The hydraulics here are murky at best. An hour goes by and then two as they ride the rising water toward the surface. The Professor calmly notes the passing strata. “Eruptive granite. We are still in the Primitive Period … Soon we shall come to the terrain of the Transition Period, and then” … The temperature rises precipitously. The water column is boiling hot. The compass “had gone mad.” The following chapter title says it: “Shot Out of a Volcano.” “Loud explosions could be heard with increasing frequency … Before long this noise had become a continuous roll of thunder.” The Professor, pleased at this, is the first to realize they’re riding an eruption. Axel is scared witless. Their ascent goes on through a night and into morning, though it’s hard to know how they can tell.

Soon lurid lights began to appear in the vertical gallery, which was growing wider; on both right and left I noticed deep corridors like huge tunnels from which thick clouds of vapour were pouring, while cracking tongues of flame were licking their walls.“Look, look, Uncle!” I cried.“Those are just sulphurous flames. Nothing could be more natural in an eruption.”

Nothing ruffles the unflappable Professor. Axel asks if they won’t be suffocated. Not a chance, says the Professor. What about the rising water? “There’s no water left, Axel,” he answers, “but a sort of lava paste which is carrying us up with it to the mouth of the crater.” This is such an exciting close-up look at the innards of a volcano that I shouldn’t carp, admittedly, but how does the raft keep from burning up if it’s riding on molten lava? Picky, picky. At last the volcano spits them out. Narrator Axel conveniently has “no clear recollection of what happened.” He comes to lying on a mountain slope and at first can’t figure out where they are. He sees olive groves and “an exquisite sea”—“this enchanted land appeared to be an island barely a few miles wide.” After a time walking through lovely countryside they encounter a little boy. Addressing him in various languages, finally they ask in Italian where they are. “Stromboli,” he replies. It’s a fitting choice. Stromboli even now has more or less regular volcanic eruptions, and they’re distinctive, intermittent blasts, not a continual flow, a type known as Strombolian. This hearkens back to good old Athanasius Kircher, whose ideas of volcanic systems are echoed here, and who stuck his own curious nose down into an Italian volcano two hundred years earlier.

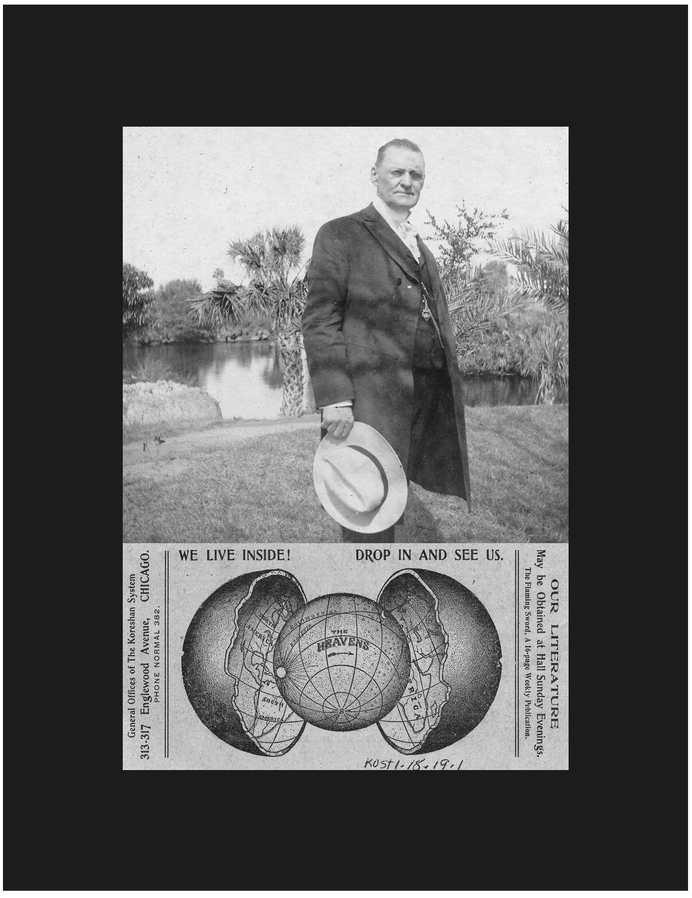

Photo of Cyrus Reed Teed (“Koresh”) on the grounds of his utopian community in Estero, Florida, along with a Koreshan promotional card. (Koreshan State Historic Site)

5

CYRUS TEED AND KORESHANITY

AROUND MIDNIGHT, EARLY AUTUMN 1869

. Yellow wavering kerosene light dances off jars of colorful compounds, retorts, odd electrical devices, and other singular equipment in a little “electro-alchemical” laboratory near Utica, New York. Thirty-year-old Cyrus Teed has been working here all day and into the night, with great result.

. Yellow wavering kerosene light dances off jars of colorful compounds, retorts, odd electrical devices, and other singular equipment in a little “electro-alchemical” laboratory near Utica, New York. Thirty-year-old Cyrus Teed has been working here all day and into the night, with great result.

As he later wrote in

The Illumination of Koresh,

he had discovered “the secret law and beheld the precipitation of golden radiations, and eagerly watched the transformation of forces to the minute molecules of golden dust as they fell in showers through the lucid electro-alchemical fluid … I had succeeded in transforming matter of one kind to its equivalent energy, and in reducing this energy, through polaric influence, to matter of another kind … The ‘philosopher’s stone’ had been discovered, and I was the humble instrument for the exploiter of so mag-nitudinous a result.”

The Illumination of Koresh,

he had discovered “the secret law and beheld the precipitation of golden radiations, and eagerly watched the transformation of forces to the minute molecules of golden dust as they fell in showers through the lucid electro-alchemical fluid … I had succeeded in transforming matter of one kind to its equivalent energy, and in reducing this energy, through polaric influence, to matter of another kind … The ‘philosopher’s stone’ had been discovered, and I was the humble instrument for the exploiter of so mag-nitudinous a result.”

Discovering the philosopher’s stone—figuring out the age-old mystery of turning base metal into gold—would seem to be enough for one day’s work. But Teed wasn’t done for the night. “I had compelled Nature to yield her secret so far as it pertained to the domain of pure physics. Now I deliberately set myself to the undertaking, of victory over death … the key of which I knew to be in the mystic hand of the alchemico-vietist.” Hard to say exactly what he meant by alchemico-vietist, but a likely deconstruction is an alchemist working on the mysteries of life forces. In any case Teed considered himself one. He next explains his view of the universe, which leads to his greater immediate goal:

I believed in the universal unity of law. I regarded the universe as an infinitely (the word is here employed in its commonly accepted use) grand and composite structure, with every part so adjusted to every other part as to constitute an integrality, constantly regenerating itself from and in itself; its structural arrangement in one common center, and its forces and laws being projected from this center, and returning to the common origin and end of all. I had taken the outermost degree of physical and material substance, that in which was the lowest degree of organic force and form, for my experimental research. Having in this material sphere made the discovery of the law of transmutation, law being universally uniform, I knew, by the accurate application of correspondential analogy to anthropostic biology, that I could cause to appear before me in a material, tangible, and objective form, my highest ideal of creative beauty, my true conception of her who must constitute the environing form of the masculinity and Fatherhood of Being, who quickeneth.

Other books

A Grave Magic: The Shadow Sorceress Book One by Sheehan, Bilinda

Heart in the Field by Dagg, Jillian

The Earthrise Trilogy by Colin Owen

02. The Shadow Dancers by Jack L. Chalker

Charity by Deneane Clark

Dawn of the Golden Promise by BJ Hoff

Dangerous Relations by Carolyn Keene

The Art of Fiction: Notes on Craft for Young Writers by Gardner, John

Kade's Dark Embrace (Immortals of New Orleans) by Grosso, Kym