Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (25 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

The Democratic Committee, chaired by Philip Isaacs, then proceeded to toss out all votes from the Estero precinct. Okay, said the Koreshans, watch this. They announced they would support non-Democratic candidates in November and set about putting together their own new Progressive Liberty party, in which, Elliott Mackle Jr. says, “Koreshans, Socialists, Republicans, dissatisfied Democrats, and other dissidents (but, notably, not Negroes) could band together in opposition to the Democratic organization.” Since they couldn’t hope to get fair coverage from Isaacs’ paper and since they had the equipment handy anyway, they started their own weekly newspaper, the

American Eagle,

in June 1906. The first issues were almost entirely devoted to politics, both stumping for the candidates they were endorsing and pounding on the incompetence and corruption of their opponents. A main target, not surprisingly, was Philip Isaacs. Naturally the

Fort Myers Press

blasted right back. The Progressive Liberty party began staging political rallies in various towns around Lee County, bringing along the Koreshan brass band to churn up enthusiasm and get everybody in the mood for the speechifying.

American Eagle,

in June 1906. The first issues were almost entirely devoted to politics, both stumping for the candidates they were endorsing and pounding on the incompetence and corruption of their opponents. A main target, not surprisingly, was Philip Isaacs. Naturally the

Fort Myers Press

blasted right back. The Progressive Liberty party began staging political rallies in various towns around Lee County, bringing along the Koreshan brass band to churn up enthusiasm and get everybody in the mood for the speechifying.

By October tempers on both sides were getting frazzled, and a disputed telephone call triggered an ugly encounter like something out of the Old West orchestrated by Monty Python.

52

It began when W. W. Pilling arrived in Fort Meyers on his way to join the Koreshan community. Finding no one there to pick him up, he sent a note to Estero and repaired for the night to a hotel belonging to a Colonel Sellers and his wife. The next morning someone called from Estero asking for him but was apparently told by Mrs. Sellers, “He is not here.” What she meant by that wasn’t made clear to the caller—whether he was still upstairs, or out, or what. She definitely did

not

mean that he wasn’t registered there, a point that didn’t get through to the Estero caller. During a second call later in the day, when Mrs. Sellers said she would get Pilling, the caller said, “I thought you told me no one by that name was stopping there.” Pilling later said that Mrs. Sellers didn’t seem upset by this exchange.

52

It began when W. W. Pilling arrived in Fort Meyers on his way to join the Koreshan community. Finding no one there to pick him up, he sent a note to Estero and repaired for the night to a hotel belonging to a Colonel Sellers and his wife. The next morning someone called from Estero asking for him but was apparently told by Mrs. Sellers, “He is not here.” What she meant by that wasn’t made clear to the caller—whether he was still upstairs, or out, or what. She definitely did

not

mean that he wasn’t registered there, a point that didn’t get through to the Estero caller. During a second call later in the day, when Mrs. Sellers said she would get Pilling, the caller said, “I thought you told me no one by that name was stopping there.” Pilling later said that Mrs. Sellers didn’t seem upset by this exchange.

Two weeks later, W. Ross Wallace, a Koreshan, and the only one running for office in the election, was accosted by Colonel Sellers on a Fort Meyers street. Sellers accused Wallace of calling Mrs. Sellers a liar, and, without waiting for a reply, began beating on him. Wallace tried to defend himself and begged the mayor of Fort Myers, who was standing nearby impassively watching this, for help, which wasn’t forthcoming. Wallace prudently fled. One week later, on October 13, Cyrus Teed, dressed as always in a spiffy black suit, was in town to meet a group of new Koreshans arriving by train from Baltimore. As he was walking down the street toward the station, he encountered Wallace, Sellers, and town marshal S. W. Sanchez in front of R. W. Gilliam’s grocery store. They’d gotten together to discuss Sellers’ attack—though why they were doing so on the street is a good question. Wallace was explaining that he was out of town campaigning on the day in question and couldn’t have been the caller. Sellers was saying that wasn’t what

he

had heard when Teed walked up to them and jumped into the discussion, offering that people often misunderstand telephone conversations but then repeating what people in Estero had overheard their caller saying.

he

had heard when Teed walked up to them and jumped into the discussion, offering that people often misunderstand telephone conversations but then repeating what people in Estero had overheard their caller saying.

“Don’t you call me a liar!” exclaimed Sellers, slugging Teed three times in the face,

whap! whap! whap!

Like the mayor before him, the town marshal stood there watching, making no move to stop it. Teed raised his hands to protect his face without fighting back. Sellers pulled a knife, but someone grabbed his arm and persuaded him to put it away.

whap! whap! whap!

Like the mayor before him, the town marshal stood there watching, making no move to stop it. Teed raised his hands to protect his face without fighting back. Sellers pulled a knife, but someone grabbed his arm and persuaded him to put it away.

Any good fight draws a crowd. Meanwhile, the train had arrived, and the Koreshans, including several young men, came upon this scene. Estero resident Richard Jentsch, seeing Teed being pummeled, slugged Sellers and was knocked down by the crowd for his trouble. Then the boys jumped in, fighting until they were bloody and their luggage dumped into the gutter.

Marshal Sanchez at last leaped into action, grabbing Teed by the lapel and shouting, “You struck him and called him a liar!”

“I did not strike him, nor call him a liar,” said Teed.

“Don’t tell me you did not strike him,” said Sanchez, slapping Teed across the face and knocking off his glasses.

Sanchez then grabbed Teed and one of the Baltimore Koreshans, telling them they were under arrest. At this moment irrepressible Jentsch, somehow shaking loose from the crowd, threw himself at Sanchez and landed a good punch. Taking his nightstick to Jentsch, Sanchez hissed, “You hit me again and I will kill you!” clubbing him repeatedly until he fell to the ground. Placing Teed, Jentsch, and Wallace under arrest, Sanchez hauled them off to jail, where each had to post a $10 bond for a court appearance the next Monday—an appearance none of them, sensibly, ever showed up for.

Fort Myers politics, circa 1906.

Teed never recovered fully from this beating. His Progressive Liberty party didn’t win a single office, but some candidates drew over 30 percent of the vote—a respectable showing given that in previous elections Democratic candidates had a virtual lock on winning. The PLP vowed they’d get ’em next time but didn’t. Teed withdrew from public view and spent the winter of 1906–1907 writing a

novel.

Its title was

The Great Red Dragon, or, The Flaming Devil of the Orient,

a book at once millenarian (no surprise there), anticapitalist, and apocalyptically racist (the bad guys are an invading Oriental army). Elliott Mackle Jr. summarizes the plot as follows:

novel.

Its title was

The Great Red Dragon, or, The Flaming Devil of the Orient,

a book at once millenarian (no surprise there), anticapitalist, and apocalyptically racist (the bad guys are an invading Oriental army). Elliott Mackle Jr. summarizes the plot as follows:

The leaders of capitalism and of western governments unite in agreement to enslave the masses, thus ensuring higher profits for themselves. The masses within the United States are organized by a partially-messianic general to meet this threat, and the forces of the capitalist-dominated United States government and its allies are eventually brought to terms. Japan, in the meantime, at the head of a Chinese horde, has begun a conquest of the world. Rome and Russia have been laid waste, and the Oriental forces, threatening to encircle the world, have gathered off all the coasts of the United States. The American navy is defeated, America begins to fall to the invaders, and the army of the masses—the only bulwark between Western civilization and Oriental savagery—withdraws to northern Florida. The Orientals are eventually defeated by an aerial navy of “anti-gravic” platforms which fire ball bearings upon the invaders. By the use of the platforms, which were manufactured at Estero, together with high ideals and truth, the forces of righteousness conquer the world. Assisted by a beautiful young woman, the triumphant leader of the masses ushers in a new dispensation. The Divine Motherhood rules over this dispensation—she is the duality of the miraculously unified leader and his assistant. Peace and tranquillity reign in the perfected New Jerusalem. And the world follows principles identical to Koreshan Universology.

By 1908 Teed had returned to his usual busy schedule, although he was in constant pain; the beating he suffered in 1906 caused lasting nerve damage that made his left arm ache, sometimes excruciatingly so. In May he and Mrs. Ordway went to Washington, DC, and spent the summer helping the new colony there, probably in part because even muggy Washington was more comfortable than summertime in pre-air-conditioning Florida. The Koreshans participated in the political activity leading up to the fall elections, but in a subdued way. When Teed and Mrs. Ordway returned to Estero in early October, he was clearly in decline. For the first time Mrs. Ordway prayed for him before the gathered assembly; there was no longer an attempt to keep his condition secret. Gustav Faber, a Koreshan living in Washington State who was a nurse during the Spanish-American War, came all the way to Estero to care for him. Teed was moved to La Partita, a house the Koreshans had built on the southern tip of Estero Island, and there Faber gave Teed saltwater baths and tried to cure him with an “electrotherapeutic machine” he had invented.

53

During these last days, Teed was heard to exclaim, “O Jerusalem, take me!”

53

During these last days, Teed was heard to exclaim, “O Jerusalem, take me!”

He died at this island cottage on December 22, 1908.

Teed had preached reincarnation and, beyond that, physical immortality for himself. He claimed to be capable of what he called theocrasis, “the incorruptible dissolution of the physical body by electro-magnetic combustion.” This is yet another of his opaque coinages and definitions, but it seems to mean that through this mysterious electromagnetic combustion, his body would renew itself. He would come back!

His more devout believers were certain this was true—and wouldn’t Christmas, three days later, be perfectly apt? They refused to bury him, and his body was returned to Estero, where it was placed in state and the vigil began. Christmas came and went, and Teed’s body was showing no signs of reviving. To the contrary, it was beginning to get pretty ripe in the unseasonably hot weather. Health officials from Fort Myers showed up, took one look, pronounced him dead, and insisted that he be buried immediately. A simple concrete tomb was prepared on Estero Island, and Teed was interred there. Some of the more fanatical believers, however, were unsatisfied with this outcome, and one dark night tried to break into the tomb to get a look, convinced he wasn’t really gone for good. A watchman was put on nightly duty. As Carl Carmer relates it:

Night after night, among the wild mangroves and the coconuts and mango trees, Carl Luettich stared into the blackness that surrounded the circle of light in which he sat. Once, just before dawn, he fell asleep and the fanatics came again and opened a side of the tomb before sunlight frightened them away. Carl Luettich was more alert after that, but watching the tomb was not necessary much longer.

This was because a hurricane and tidal wave hit the island on October 23, 1921, washing both the mausoleum and the cottage out to sea. Only the headstone was recovered, which is now on display in the auditorium of the Koreshan Unity Headquarters Building. It says simply:

CYRUSShepherd Stone of Israel

The aftermath of Teed’s death was a predictable scramble for power with certain black humor flourishes. Nurse Gustav Faber claimed to be Teed’s successor, saying Teed had named him the new leader with his final breaths and transferred authority through “theocrasis.” But the Estero Koreshans weren’t having it, and Faber departed early in 1909. Strangely, Teed’s longtime spiritual companion, Mrs. Ordway, had been off in Washington during Teed’s final days and didn’t make it back to Estero until December 27. She would seem his natural successor, but this was resisted, possibly by sexist elements who wouldn’t abide a woman leader, possibly because a Koreshan furniture works in Bristol, Tennessee, named for her, was going under, and the debt weighed on the community. In any case, she rather rapidly packed up and left with a few of her more dedicated followers to start up her own Koreshan commune in Seffner, Florida. It soon failed, and she married Charles A. Graves, recently mayor of Estero. They eventually settled in St. Petersburg, where she remained until her death in 1923.

The Estero community continued in diminishing circumstances for many years, until the land was finally given to the state by the last four members in 1961. The grounds are now the Koreshan Historic Site, which opened to the public in 1967. Across Highway 41 from the Koreshan Historic Site, in a modest building, the Koreshan Unity Foundation is still engaged in keeping Cyrus Teed’s legacy and ideas alive.

Teed’s tomb on Estero Island. (Koreshan State Historic Site)

The Goddess of Atvαtαbαr

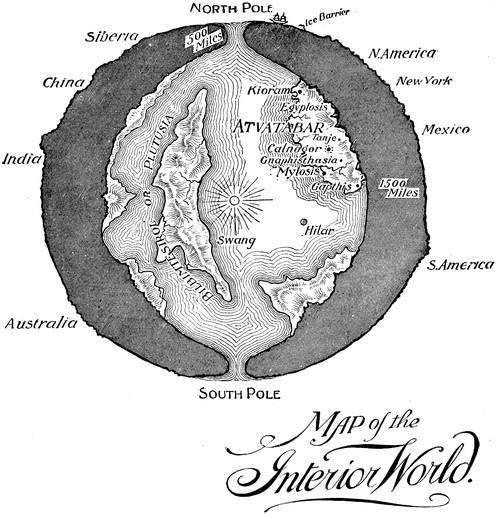

(1892) by William R. Bradshaw was one of many hollow earth novels that appeared toward the end of the nineteenth century. This is a map of that interior world, reached by explorer Lexington White through a convenient Symmes’ Hole at the North Pole.

(1892) by William R. Bradshaw was one of many hollow earth novels that appeared toward the end of the nineteenth century. This is a map of that interior world, reached by explorer Lexington White through a convenient Symmes’ Hole at the North Pole.

Other books

Harshini by Jennifer Fallon

The Reluctant Bride by Beverley Eikli

The Dominion Key by Lee Bacon

Ride the Star Winds by A. Bertram Chandler

The Extra by Kenneth Rosenberg

The Powder River by Win Blevins

Carry Me Like Water by Benjamin Alire Saenz

In a Treacherous Court by Michelle Diener

A Deadly Injustice by Ian Morson