Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (33 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

They’ve come to rest in a field of grass and clover as tall as a house, with red and yellow flowers the size of easy chairs. The Professor decides it’s due to some unusual quality of the atmosphere and quickly produces a cosmological theory: “I believe we are on a sort of small earth that is inside the larger one we live on. This sphere floats in space, just as our earth does, and we have passed through a void that lies between our globe and this interior one. I think this new earth is about a quarter the size of ours and in some respects the same. In others it is vastly different.”

Mark, one of the boys, says he thinks he saw a strange figure fleeing the ship after they landed, but nobody pays attention to him. Soon they begin exploring, and it’s trouble right away. Jack stumbles down a steep hill into the cup of an enormous pitcher plant—those gently carnivorous plants best known on the surface as the Venus flytrap. Jack’s fallen in and is covered with its sweet digestive goo. But they chop him out before any harm is done. Ants the size of “large rats” come swarming to the mess, as the intrepid explorers move on to an orchard where six-foot peaches grow on vines and several grasshoppers the size of motorcycles are pushing a ripe one along. Andy characteristically wants to blast a couple to kingdom come but is dissuaded on the grounds that they probably aren’t very good to eat.

After many days of travel and a close encounter with a deadly half-plant, half-animal “snake tree,” they come upon something truly weird—a delirium tremens monstrosity that “had the body of a bear, but the feet and legs were those of an alligator, while the tail trailed out behind like a snake, and the head had a long snout, not unlike the trunk of an elephant. The creature was about ten feet long and five feet in height.” Andy is eager to shoot it, but it’s suddenly caught in a geyser and drops to the ground dead—not far from a twelve-foot giant. Only Mark sees him before he disappears into the underbrush. Can it be their stowaway?

They continue for several days more, until they come upon a village, whose buildings consist of mounds rudely made from clay—dwellings of a half-civilized Mud Age people. Suddenly, “seeming to rise from the very ground, all about the ship, there appeared a throng of men … Not one was less than ten feet tall, and some were nearly fifteen! ‘The giants have us!’ cried Bill, as he saw the horde of creatures surrounding the ship.”

A brief battle ensues, and the giants prove to practically be made of mud themselves. A peculiarity of increased gravity has made the giants’ bodies soft and pliant, unmuscular. “They look like men made of putty! They’re soft as snow men!” Our explorers prevail for a while, but sheer numbers do them in and they’re finally captured. The Putty People are about to execute them, when a figure even taller than the rest appears wearing golden armor and bearing a golden sword. He orders everyone to stop! It’s the Putty People’s long-lost king, who was the mysterious stowaway on the

Mermaid.

He got stuck on the surface after riding a waterspout up, and he is eternally grateful to the Professor and his crew for bringing him back home. His land is their land.

Mermaid.

He got stuck on the surface after riding a waterspout up, and he is eternally grateful to the Professor and his crew for bringing him back home. His land is their land.

He directs them to an abandoned temple heaped with diamonds and gold, telling them to take as much as they like. They find it and load up, but then realize their entry hole has been closed by an earthquake. The only way back to the surface is to ride the waterspout. Luckily the Professor has brought along a waterproof escape cylinder that’s just the ticket for riding the waterspout, but they’ll only have room for a few token diamonds in their pockets during the return ride. So it’s up, up, and away in an exit borrowed from Verne. They float in the Atlantic until they’re picked up by a passing ship and soon are back on the island in Maine. In an ending duly in keeping with the American Dream, those pocketfuls of diamonds they brought back make them all rich: “There was money enough so that they all could live in comfort, the rest of their lives.” The Professor feels it’s time to hang up his inventor’s cap and retire. The rest, in a true sign of the times, decide to invest the money they get for the jewels “in different business ventures, and each one did well.” They all live happily ever after through business savvy!

The number of hollow earth novels dropped off precipitously after 1910. One likely factor was increased scientific knowledge. Information has a way of dousing the fires of dreams. By then repeated expeditions seeking both poles had failed to confirm Symmes’ Holes, so closely tied to the notion of a hollow earth. Until 1910 or so, the hollow earth conceit remained a terrific vehicle for adventure and utopian speculation. It provided a handy alternate world very much like our own and at least a marginally believable one. As polar exploration advanced and increasingly established that there were no inviting holes at the poles surrounded by a temperate open polar sea, the required suspension of disbelief became more difficult.

Nevertheless, a few true believers continued to hold on, despite all evidence to the contrary, and two nonfiction books appeared filled with “scientific” proof of the hollow earth.

In 1906, when William T. Reed’s

The Phantom of the Poles

appeared, though Peary had made it to the North Pole, and Reed blithely argued that the poles hadn’t been discovered because

they don’t exist!

Instead, there are openings into the hollow earth where the poles are supposed to be, so vast, and their inclination so gradual, that various polar explorers have traveled a short way into them without realizing it: “I claim that the earth is not only hollow,” Reed wrote, “but that all, or nearly all, of the explorers have spent much of their time past the turning-point, and have had a look into the interior of the earth.” He accounts for the aurora borealis as “the reflection of a fire within the earth,” and is convinced meteors don’t come from outer space, but are rather being spat out by volcanoes in the interior—along with a host of other earnestly misinformed thoughts on the working of the compass, and the origins of glaciers, arctic dust, and driftwood, among others. And what’s down there? “That, of course, is speculative … It is not like the question, ‘Is the earth hollow?’ We know that it is, but do not know what will be found in its interior.” His guess? “From what I am able to gather … game of all kinds—tropical and arctic—will be found there; for both warm and cold climates must be in the interior—warm inland and cold near the poles. Sea monsters, and possibly the much-talked of sea serpent, may also be found, and vast territories of arable land for farming purposes. Minerals may be found in great quantities, and gems of all kinds. We may succeed, too, in finding large quantities of radium, which would be used to relieve the darkness if it should be unusually dark. I also believe the interior of the earth will be found inhabited. The race or races may be varied, but some at least will be of the Eskimo race, who have found their way in from the exterior.” Like Symmes, he urges immediate exploration and colonization. “[The interior] can be made accessible to mankind with one-fourth the outlay of treasure, time, and life that it cost to build the subway in New York City. The number of people that can find comfortable homes (if it not already be occupied) will be billions.” His whole case, presented in 283 obsessive pages, is little more than a rehash of Symmes’ ideas from a hundred years earlier.

The Phantom of the Poles

appeared, though Peary had made it to the North Pole, and Reed blithely argued that the poles hadn’t been discovered because

they don’t exist!

Instead, there are openings into the hollow earth where the poles are supposed to be, so vast, and their inclination so gradual, that various polar explorers have traveled a short way into them without realizing it: “I claim that the earth is not only hollow,” Reed wrote, “but that all, or nearly all, of the explorers have spent much of their time past the turning-point, and have had a look into the interior of the earth.” He accounts for the aurora borealis as “the reflection of a fire within the earth,” and is convinced meteors don’t come from outer space, but are rather being spat out by volcanoes in the interior—along with a host of other earnestly misinformed thoughts on the working of the compass, and the origins of glaciers, arctic dust, and driftwood, among others. And what’s down there? “That, of course, is speculative … It is not like the question, ‘Is the earth hollow?’ We know that it is, but do not know what will be found in its interior.” His guess? “From what I am able to gather … game of all kinds—tropical and arctic—will be found there; for both warm and cold climates must be in the interior—warm inland and cold near the poles. Sea monsters, and possibly the much-talked of sea serpent, may also be found, and vast territories of arable land for farming purposes. Minerals may be found in great quantities, and gems of all kinds. We may succeed, too, in finding large quantities of radium, which would be used to relieve the darkness if it should be unusually dark. I also believe the interior of the earth will be found inhabited. The race or races may be varied, but some at least will be of the Eskimo race, who have found their way in from the exterior.” Like Symmes, he urges immediate exploration and colonization. “[The interior] can be made accessible to mankind with one-fourth the outlay of treasure, time, and life that it cost to build the subway in New York City. The number of people that can find comfortable homes (if it not already be occupied) will be billions.” His whole case, presented in 283 obsessive pages, is little more than a rehash of Symmes’ ideas from a hundred years earlier.

Marshall Gardner’s

A Journey to the Earth’s Interior; or, Have the Poles Really Been Discovered?

(1913) covers the same hollow ground. Gardner, who made his living as a maintenance man in an Aurora, Illinois, corset factory, posits a central sun six hundred miles across, a leftover bit of nebula from the time the earth was first formed. Reflected light from this inner sun accounts for the aurora borealis. Gardner was most fired up about the possibilities of developing this interior world (particularly mining), which he was certain contained a bonanza of diamonds, platinum, and gold. And this should be done not out of greed but as a patriotic act. Writing on the eve of World War I, he asked, “Do we want one of the autocratic countries of Europe to perpetuate in this new world all the old evils of colonial oppression and exploitation?” Not on your life. America, “with her high civilization, her free institutions, her humanity,” has a “duty” to get there first. And “our country has the men, the aeroplane, the enterprise, and the capital” to pull it off.

A Journey to the Earth’s Interior; or, Have the Poles Really Been Discovered?

(1913) covers the same hollow ground. Gardner, who made his living as a maintenance man in an Aurora, Illinois, corset factory, posits a central sun six hundred miles across, a leftover bit of nebula from the time the earth was first formed. Reflected light from this inner sun accounts for the aurora borealis. Gardner was most fired up about the possibilities of developing this interior world (particularly mining), which he was certain contained a bonanza of diamonds, platinum, and gold. And this should be done not out of greed but as a patriotic act. Writing on the eve of World War I, he asked, “Do we want one of the autocratic countries of Europe to perpetuate in this new world all the old evils of colonial oppression and exploitation?” Not on your life. America, “with her high civilization, her free institutions, her humanity,” has a “duty” to get there first. And “our country has the men, the aeroplane, the enterprise, and the capital” to pull it off.

With Gardner and Reed we enter the modern phase of hollow earthology —earnest believers marshaling increasingly desperate (and increasingly detailed) evidence to support a theory increasingly at odds with the growing weight of scientific data. But as we’ll see, even today a few true believers continue to hang in there, despite all evidence to the contrary.

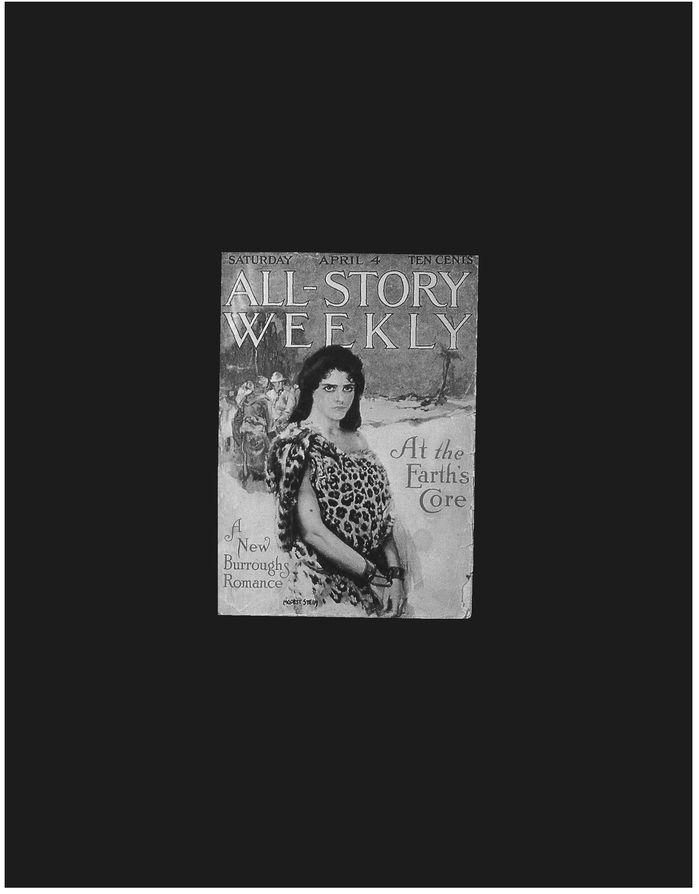

“At the Earth’s Core,” published in

All-Story

magazine, which featured a pensive-looking Dian the Beautiful on the cover. (© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

All-Story

magazine, which featured a pensive-looking Dian the Beautiful on the cover. (© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

7

EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS AT THE EARTH’S CORE

THE NUMBER OF HOLLOW EARTH NOVELS

dropped off drastically after 1910, largely because polar exploration revealed no Symmes’ holes. Consequently it was harder for readers (and writers) to create the suspension of disbelief needed to make such stories work. Something similar happened in the 1960s in regard to Venus. Its thick atmosphere and proximity to the sun had allowed generations of science fiction writers to create stories set in a steamy tropical wonderland of mysterious jungles and strange creatures. But then the facts intruded: under all those clouds Venus is too hot for life and too dry. And so the fetching bosomy Venusian maidens that routinely adorned pulp magazine covers from the 1930s through the 1950s disappeared. And although they didn’t disappear completely, stories set in the hollow earth began to seem too far-fetched once science established the geophysical impossibility of a hollow earth.

dropped off drastically after 1910, largely because polar exploration revealed no Symmes’ holes. Consequently it was harder for readers (and writers) to create the suspension of disbelief needed to make such stories work. Something similar happened in the 1960s in regard to Venus. Its thick atmosphere and proximity to the sun had allowed generations of science fiction writers to create stories set in a steamy tropical wonderland of mysterious jungles and strange creatures. But then the facts intruded: under all those clouds Venus is too hot for life and too dry. And so the fetching bosomy Venusian maidens that routinely adorned pulp magazine covers from the 1930s through the 1950s disappeared. And although they didn’t disappear completely, stories set in the hollow earth began to seem too far-fetched once science established the geophysical impossibility of a hollow earth.

But one writer remained undaunted by facts to the contrary.

Edgar Rice Burroughs liked the idea of a hollow earth well enough to set six novels and several short stories in what he called Pellucidar, starting with

At the Earth’s Core,

first published serially in 1914 in

All-Story Weekly.

At the Earth’s Core,

first published serially in 1914 in

All-Story Weekly.

Burroughs’s life before turning to writing at the age of thirty-five was like Baum’s compounded for the worse—a study in lack of direction and repeated failure. He was born into a prosperous Chicago family in 1875. His father was a wealthy whiskey distiller, which proved ironic given Burroughs’s later struggle with alcoholism. As a teenager he’d been sent to the prestigious Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, and was elected class president in 1892—but got yanked out of school by his father that same year for low grades and was forcibly relocated to the Michigan Military Academy north of Detroit, where he remained for five years. In 1896, he joined the army, but soon found himself bored stiff at the Arizona fort where he was stationed and began writing to his father, begging him to get him out. Special discharge papers signed by the secretary of war arrived early in 1897.

Years of upheaval followed. His brother Harry owned a cattle ranch in Idaho, and Burroughs’s first job after leaving the army was as a cowboy, helping his brother drive a herd of starving Mexican cattle from Nogales to Kansas City. By summer he had enrolled as a student at Chicago’s Art Institute, but it didn’t last. Early in 1898, with things heating up in Cuba, Burroughs wrote Teddy Roosevelt offering to join his Rough Riders—but was rejected. By June of that year he’d opened a stationery shop in Pocatello, Idaho, but he was back to cowboying with his brother the following spring, and then landed in Chicago again in June as treasurer of his father’s American Battery Company—the distillery burned down in 1885, and his father, resilient, had shifted to supplying the nascent automobile industry.

Burroughs married Emma, his longtime sweetheart, in 1900, and stayed with dad’s battery company for three more years—but then a roller-coaster ride of jobs followed. By then he was beginning to do some writing and cartooning, but hadn’t figured out how to make a living at it. He joined his brother Harry in an Idaho gold dredging operation in 1903, but that went bust in less than a year. On to Salt Lake City, where he became a railroad policeman for a time, and then it was back to Chicago. There, for the next seven years, poor Burroughs tried everything he could think of to support Emma and his growing family: high-rise timekeeper, door-to-door book salesman, lightbulb salesman, accountant, manager of the stenographic department at Sears, partner in his own short-lived advertising agency, office manager for a firm selling a supposed cure for alcoholism called Alcola, and a sales agent for a pencil sharpener company. This last job involved monitoring ads in pulp magazines—but Burroughs found himself more interested in reading the stories in these magazines than the ads he was supposed to be tracking. And the lightbulb lit.

I can do this!

In 1911, as the company was heading under, using the backs of letterhead stationery from his former failed businesses, Burroughs began handwriting what became

Under the Moons of Mars,

featuring John Carter, the first of his invincible heroes. He sent it out, and in August came a letter of acceptance from the editor of

All-Story.

Though Burroughs was still writing in his spare time—or stealing time from his latest job, working for brother Coleman’s stationery manufacturing company on West Kinzie Street, Chicago—by December 1911, he’d started writing

Tarzan of the Apes,

which he also sold to

All-Story

(for $700).

I can do this!

In 1911, as the company was heading under, using the backs of letterhead stationery from his former failed businesses, Burroughs began handwriting what became

Under the Moons of Mars,

featuring John Carter, the first of his invincible heroes. He sent it out, and in August came a letter of acceptance from the editor of

All-Story.

Though Burroughs was still writing in his spare time—or stealing time from his latest job, working for brother Coleman’s stationery manufacturing company on West Kinzie Street, Chicago—by December 1911, he’d started writing

Tarzan of the Apes,

which he also sold to

All-Story

(for $700).

Other books

Hacedor de estrellas by Olaf Stapledon

Emily's Reasons Why Not by Carrie Gerlach

Gamble on Engagement by Rachel Astor

Blood Storm: The Second Book of Lharmell by Rhiannon Hart

The Vengeance Man by Macrae, John

Time Patrol by Poul Anderson

True (. . . Sort Of) by Katherine Hannigan

Billy and Me by Giovanna Fletcher

El viejo y el mar by Ernest Hemingway