Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing (11 page)

Read Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing Online

Authors: Melissa Mohr

Tags: #History, #Social History, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Linguistics, #General

Despite the Israelites’ occasional backsliding into idolatry, Yahweh’s trusty weapons, oaths and vows, stand him in good stead, and in the end he wins his war against the other gods. Partly by encouraging swearing and vowing, Yahweh goes from being a fairly minor god among many to being the best god among many and then to being the only God who exists.

Fallen Idols and God’s Wife

What happens to the other gods, Yahweh’s competition? Historically, they fell into obscurity as the peoples, cities, or empires they were supposed to protect were conquered or collapsed into ruin. In the Bible, they are disposed of in two ways. On the text’s surface, narrative level, Yahweh has several face-offs with other gods, which he wins handily. He triumphs, for example, over Baal. His prophet Elijah arranges a contest in which the first god to set a pile of wood on fire wins (1 Kings 18:20–40). The 450 priests of Baal try everything to get their god to start a fire, but nothing happens. When Elijah, the Lord’s lone prophet, asks Yahweh to light his pile, it goes up spectacularly, even though Elijah has drenched his wood with water. The people watching feel that this settles the matter—they declare, “The Lord indeed is God,” and capture the priests of Baal so that Elijah can kill them, all 450.

On a deeper level, Yahweh subsumes Baal.

He takes over many of his rival

storm god’s most famous mythological deeds. Baal battles

Lotan, a seven-headed dragon; Yahweh defeats Leviathan, a great sea beast (and, as it happens,

Leviathan

is the Hebrew name for Lotan). Baal fights with Yamm, a sea god, and Mot, god of death; Yahweh conquers sea and death (Ps. 74:12–17; Isa. 25:8). These battles were major parts of Baal’s mythology, but in the Bible they are mentioned only in passing, and only in generalized form. Yahweh can fight “sea” or even “Sea,” as some translations put it, but he can’t fight Yamm. If he did battle directly with another god, that would be an outright acknowledgment that other deities existed, and Yahweh is now too powerful and dignified to acknowledge the existence of rivals.

Yahweh also takes on many attributes of El

, the most important Canaanite god, including his name. Yahweh is called El—“I am God [El], and there is no other” (Is. 45:22)—and also El Elyon (El most high), El Shaddai (God of the uncultivated fields, God almighty), Elohim (God, gods), and El Elohe Israel (El, the god of Israel), among others. There is an interesting passage where Yahweh seems to acknowledge this syncretism, the melding of religious beliefs or concepts. In Exodus, he declares that he is changing his name—it used to be El, but from now on it’s going to be Yahweh. God tells Moses: “I am the Lord [Yahweh]. I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as God Almighty [El Shaddai], but by my name ‘The Lord’ [Yahweh] I did not make myself known to them” (Ex. 6:2–3). Anybody who used to pray to El should now worship Yahweh—Yahweh is the new and improved El.

Yahweh had perhaps the hardest time displacing

the rival who was closest to him, his consort, Asherah. Many scholars believe that Yahweh adopted not just El’s name and titles but also those of his partner, at least in what is called popular or folk religion, as opposed to the priestly, orthodox religion of Deuteronomy and Leviticus. In the Near East, we have seen, gods often came paired with goddesses—El and Asherah, Baal and Anat/Astarte, Horus and Hathor (Egyptian deities)—and it would be highly unusual for a god

not

to have a consort or to show any interest in sexual relations, whether

with other deities, humans, animals, humans in the shape of animals, or what have you. Archaeologists have found some evidence that Yahweh was not entirely out of the normal Near Eastern way in these matters, in the form of inscriptions linking his name and Asherah’s. Several come from a complex of buildings called Kuntillet Ajrud in the eastern Sinai Desert. Kuntillet Ajrud was a caravanserai—a stopover along a route between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean that served as a defensive fort and inn for travelers, as well as a shrine. “

To [Y]ahweh [of] Teiman

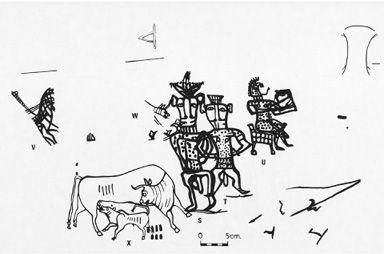

[Yemen] and to his Ashera[h]” is written on a wall in the shrine, while two storage jars are inscribed “I [b]lessed you by [or ‘to’] Yahweh of Samaria and by his Asherah” and “Yahweh of Teiman and his Asherah.” The pictures below were found on the former jar, and many scholars interpret them as an illustration of the inscription, which would yield a rare portrait not only of the famously image-averse Yahweh but also of his consort. But which image depicts Yahweh and Asherah? Yahweh might be the calf and Asherah the cow. Or Yahweh might be the obviously male figure and Asherah the also pretty obviously male figure next to him (this figure has breasts, too). Or Asherah is the lyre player in the background, Yahweh is the male figure, and the one with a penis and breasts is … who knows? The picture below, from the same jar, is easier to interpret—it is Asherah as the tree of life, upon whom the standing goats are feeding.

Pictures from the

pithos

inscribed “I [b]lessed you by [or ‘to’] Yahweh of Samaria and by his Asherah.”

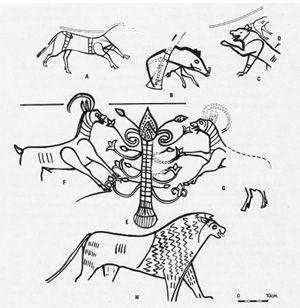

Asherah, from the same

pithos

.

Asherah is originally included in Elijah’s wood-burning challenge—her four hundred prophets are supposed to light a fire too. (She also has a royal supporter, the wicked queen Jezebel.) We

hear all about Yahweh’s subsequent victory over Baal and the slaughter of his prophets, as archaeologist William Dever notes, but nothing more is reported about Asherah. Did she manage to light a fire too?

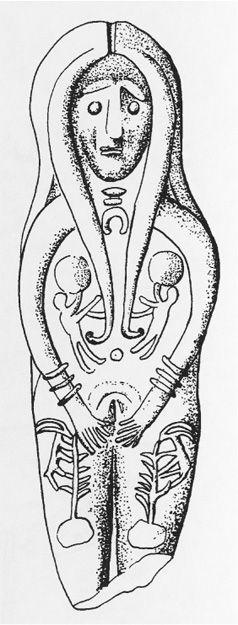

Asherah was worshipped by erecting sacred poles or planting trees, as her symbol was the tree of life—she was a goddess of fertility. On pots, pendants, seals, and offering stands, she was often depicted as a tree or bush flanked by two animals standing on their hind legs, who are nibbling her leaves—she gives nourishment. Sometimes the bush they are nibbling is pretty explicitly her pubic hair.

In the Bible, there is only one moment of happy union for Yahweh and Asherah, involving an oath. It occurs after Abram cuts a covenant with the Philistine king Abimelech, resolving a dispute they had been having. Abraham claims that Abimelech’s servants have seized a well that belongs to him. Wary of antagonizing someone so obviously under the protection of a powerful god, Abimelech immediately cedes the well to Abraham, and “the two men made a covenant… . Therefore that place was called Beer-sheba [Heb.: “well of the oath”]; because there both of them swore an oath” (Gen. 21:27–31). Abimelech goes on his way, while Abraham “planted a tamarisk tree in Beer-sheba, and called there on the name of the Lord, the Everlasting God” (Gen. 21:33). In the Hebrew, Abraham calls on “El Olam,” “El the everlasting” or “El the eternal”—this is one of the places in the Bible where we can see evidence of the convergence of Yahweh and El. Then he invokes Asherah, El/Yahweh’s consort, by planting one of her sacred trees. It seems that he would like both gods to witness his covenant with Abimelech, Yahweh and his Asherah.

(Though he is the founder of the Jewish nation, Abraham is not a good role model when it comes to swearing. He not only plants a tree for Asherah, he makes his servant swear an oath on his genitals. He wants his servant to travel back to his homeland to find a wife for his son, Isaac, and engages him to do it with an oath: “

put your hand under my thigh

,” he tells the servant, “and I will make you swear by the Lord, the God of heaven and earth” [Gen. 24:2–4]. In the Bible

thigh

sometimes means what it appears to, but more often it refers to the penis and/or balls [and occasionally to the female genitals]. This is a very old form of swearing, an oath not by God but by Abraham’s powerful reproductive organs, which founded the tribe of Israel. Of course the servant has to swear by God as well—Abraham is hedging his bets. This oath is used once more in Genesis, when Jacob makes Joseph put his hand under his thigh and swear to bury him with his ancestors [Gen. 47:29], but then it falls into disuse. God wants people to swear by him, not by their own procreative powers.)

*

Goats nibbling Asherah’s, ahem, bush.

While ordinary Israelites who practiced folk religion and even the first patriarch, Abraham, paired Yahweh with Asherah, the priestly authors of Leviticus and Deuteronomy rejected her. “You shall not plant any tree as a sacred pole beside the altar that you make for the Lord your God; nor shall you set up a stone pillar—things that the Lord your God hates,” Deuteronomy 16:21 instructs believers. In Exodus 34:13–14, God warns the Israelites not to make covenants with the inhabitants of Canaan—instead they should “tear down their altars, break their pillars, and cut down their sacred poles (for you shall worship no other god, because the Lord, whose name is Jealous, is a jealous God).” In both cases, what gets translated as “sacred pole” is the word

asherah

—these poles or trees are sacred to Yahweh’s (former) partner but must now be destroyed as relics of idol worship, along with stone pillars used in the worship of Baal and other Canaanite gods.

Eventually Yahweh won out over Asherah as well, and monotheism was born. These traces of other gods, which we’ve made so much of, are just that, traces. The Bible on the whole did a much more thorough job of erasing evidence of Yahweh’s battles than did those monks when they wrote over Archimedes.

There is a famous statue

(actually a pair of them) of a black and gold goat, standing on its hind legs and supported by a stylized tree, that was unearthed in Ur, in modern-day Iraq. It probably represents Asherah, or at any rate is very much in line with her iconography—the goddess as sacred tree, flanked by goats standing on their hind legs and nibbling. The figure is known as the “Ram in a Thicket,” though. The archaeologist who discovered it named it after the scapegoat God provides when Abraham is about to sacrifice his son: “And Abraham looked up and saw a ram, caught in a thicket by its horns” (Gen. 22:13). Poor Asherah has no claim anymore even on her most famous symbol. Yahweh’s victory over the other gods, even his nearest and dearest, was so complete that the memory of them was practically erased. God’s covenants (which are themselves oaths) with the Jews, his commands to swear by him, and his prohibition of oaths on other gods were key factors in his victory.