Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing (5 page)

Read Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing Online

Authors: Melissa Mohr

Tags: #History, #Social History, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Linguistics, #General

This epigram highlights the connection between sex and violence so often found in obscene words and slang. In Latin, and to a smaller extent in English,

the penis is a weapon

—

telum

(spear),

hasta

(javelin)—and

sex is depicted as brutal

, in slang such as

caedo

(to cut),

battuo

(to beat), or the English

banging, drilling, nailing

, and so on. The Latin word

vagina

, in fact, originally referred to the sheath of a sword. This connection between sex and violence was quite literal in the Perusine War.

The opposing sides lobbed sling bullets

at one another engraved with messages such as “Fulvia’s clitoris” and “Octavian sucks cock.”

A final difference between

futuo

and the English

f

-word is that in Latin, women couldn’t fuck.

Futuo

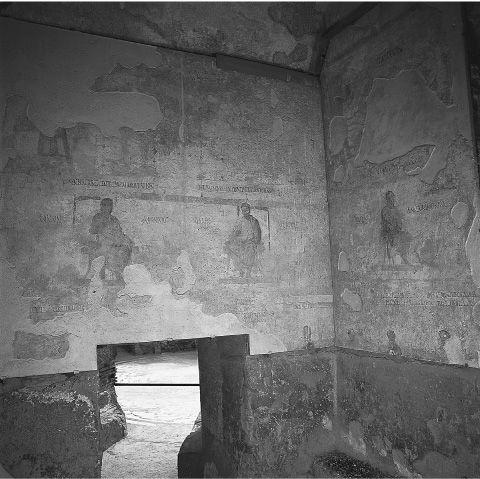

referred only to the man’s participation in the act. Women could be fucked, as one likely prostitute wrote on the walls of the Pompeian brothel:

Fututa sum hic

(I have been fucked here). Though the woman’s part of

fututio

is referred to in the passive voice, that doesn’t mean that Roman women just lay there. Latin has a unique verb for what women do—

criso

, which might be translated as “wriggling.” It is also obscene, though not as much so as

futuo

, and far less common. The Romans preferred to talk and joke about the male role in the action.

landica = an andiron

*

—Thomas Holyoake,

A Large Dictionary in Three Parts

, 1676

Some Roman women

were

capable of

fututio

, though not “normal” ones. They were the lesbians, called

tribades

, who were thought to have a massively overdeveloped clitoris that they used like a penis. (

Lesbian

comes from the Greek word

lesbiazein

, “to do it Lesbos style.” In ancient times, however, the inhabitants of Lesbos were known not for girl-on-girl action but for fellatio.)

Lesbian

as we know it today came into use in English only around the turn of the twentieth century. Before then,

tribade

was still the ordinary word

for a woman who “practices unnatural vice,” as the

Oxford English Dictionary

put it until 1989. Martial attacks one such

tribas

, Bassa, recounting how he had thought that she was a woman of great moral probity because she was never in the company of men, only other women. To his horror, he discovers that she is indeed unchaste, and in a way he hadn’t expected:

So I confess I thought you a Lucretia; but Bassa, for shame, you were a fucker [

fututor

]. You dare to join two cunts and your monstrous organ feigns masculinity.

†

Martial describes what she does by using the active form of

futuo

—she is a

fututor

, just like a man, her clitoris substituting for a penis.

The Latin word for the clitoris is, as we have seen,

landica

, and it was one of the worst in the language—almost too bad even for epigrams. We know it mostly from graffiti such as “Eupl[i]a, loose,

of large clitoris” (

Eupla laxa landicosa

). This is not praise of said Euplia. A

cunnus laxus

was sexually undesirable, and might even hint at character flaws—loose

cunnus

, loose morals. And “of large clitoris” links her with the lesbians.

Landica

was such a bad word in part because of its primacy in the perverted (according to the Romans) relations of the

tribades

. Martial’s epigram shares this ancient disgust—Bassa “dares” to join cunts, as if this is in violation of the natural order, and her clitoris is “monstrous,” not simply “big.” It is horrific that women have sex like men. (It is also, as various scholars of Roman sexuality note,

most likely a misrepresentation

of what Roman lesbians actually did with each other.)

But there are other reasons

landica

is so obscene, ones that, to modern eyes, reflect more positively on the ancient Romans. People swear about what they care about, and the Romans cared about the clitoris.

They thought that both male and female partners

in intercourse had to achieve orgasm for conception to occur, a wrong, but gallant, idea. Medical writings show that they knew where the clitoris was, and what it did—that stimulating it would help bring about those orgasms thought to be necessary for the creation of sons, soldiers, empire.

In English, we don’t really have a swearword for the clitoris. There’s

clit

, but it’s just not that offensive, and it is rarely used. If you call someone a

clit

, you’ll probably get puzzled laughter, or even a pitying look. Perhaps English-speaking women should be insulted that

clitface

and

clit for brains

are more funny than shocking, that the clitoris doesn’t register high enough in the cultural consciousness to deserve its own swearword.

I don’t mean to portray the Romans either as medical experts or as proto-Casanovas who devoted their time to unlocking the sexual secrets of the female body.

They were plenty misinformed about sex

and about women. They believed, for example, that women provided the “matter” during conception, and men the “form.” Women were the “dirt,” according to the Greek authority

on everything, Aristotle; men planted the “seed.” And bodies were regulated by a balance of four humors. Men were hot and dry; women were cold and wet. This theory of humors is critical to understanding Roman views of sexuality. The boundary between male and female was not as fixed as it is today. If a woman “heated up,” she could become a man; if a man “cooled down,” he could become a woman.

Tribades

, then, were women who had gotten hotter, drying their “natural” moisture, and causing their clitoris to grow until it became like a penis. Today, people can change sex completely through surgery, or partly through hormones or cross-dressing. But it is hard, requiring money and determination. In ancient Rome, it was easy—too easy, it was feared. Hang around females too long, spend time playing the lyre instead of performing the military exercises that burned off moisture and kept your temperature up, and you just might find yourself turning into a woman.

Landica

and

futuo

are words that on one level are very similar to their English counterparts. The Latin

f

-word means the same thing and is of the same register as the English one, and it is possible at least to imagine an English in which

clit

is a swearword like

cock

and

dick

, since it too is a direct word for a body part in a taboo zone. But the words also reveal some differences, particularly in the way Romans thought about the role of women during sex, and about the physiology that helped to determine that role.

Now we come to the really strange words, ones we don’t have in English, or ones that are so different from their English equivalents that they are hardly recognizable. These words reveal fundamental differences in the way Romans thought about sexuality, masculinity, power, and the concept of obscenity itself.

irrumo = to suck in

pedico = ?

—Thomas Thomas,

Dictionarium

, 1587

The Latin word for man is

vir

, but in Rome this was not merely an indication of biological sex.

Vir

carried with it a set of cultural expectations

of what “real men” should be.

Viri

were freeborn citizens, exercised strong self-control, and tried to dominate others, particularly through sexual penetration. (Think twice if ever someone should praise you as “

vir

tuous.”) Men who didn’t fulfill these social criteria were called

homines

(a neutral word, without the glory of

vir

) or, especially in the case of slaves,

pueri

(which literally means “boys”).

What

a man did sexually played a large role in whether he was a

vir

, but

whom

he did it with didn’t matter at all. Our categories of “heterosexual” and “homosexual” were meaningless in Rome. It was assumed that “normal” men would want to sleep with women, boys, and sometimes adult men, and that each type of partner provided different pleasures and problems. What a man did with these various partners was the key thing. He must always be the active, penetrating one. He must never allow someone else to penetrate him—that would make him soft (

molles

), effeminate, less than a man.

The Latin vocabulary that developed around this sexual schema is all about the penetration of orifices.

Futuo

could be translated more literally as “to penetrate a vagina.”

Pedicare

means “to penetrate an anus.” Nothing in the verb specifies whether the anus belongs to a male or to a female—both possibilities were open to a

vir

, though the anuses of boys were generally considered more desirable. An epigram of Martial makes this vividly clear:

Catching me with a boy

, wife, you upbraid me harshly and point out that you too have an arse [

culum

]. How often did Juno say the same to her wanton Thunderer! Nonetheless he lies with strapping Ganymede. The Tirynthian used to lay aside his bow and bend Hylas over: do you think Megara had no buttocks? Fugitive Daphne tormented Phoebus: but the Oebalian boy bade those flames vanish. Though Briseis often lay with her back to Aeacus’s son, his smooth friend was closer to him. So kindly don’t give masculine names to your belongings, wife, and think of yourself as having two cunts [

cunnos

].

The wife is upset that her husband is unfaithful, not that he is what we today would call “gay.” He is

not

gay—the category “gay” did not exist in ancient Rome, in which there were no “gay” men as we know them. Berate him though his wife does for going outside the marriage, the husband’s desires are perfectly normal—

most

men wanted to sleep with both women and boys. She tells her husband that if he wants

pedicare

, he can do

her

, but he refuses, citing the examples of gods and heroes (Jupiter, Hercules, Apollo, and Achilles—not such shabby company) who have preferred their boy lovers to their wives in this respect. The poem ends with a cutting rebuke—the wife should not even use the word

culus

(ass) when referring to herself. Her ass is so different from, and inferior to, a boy’s that she should instead say she has two cunts.

The verb

irrumare

involves pretty much the only other orifice available—it means “to penetrate the mouth.”

Irrumo

is a bit different from the other verbs because, as we’ve seen, it usually carries a threat of violence. You might do it for pleasure, but part of that pleasure would be in humiliating the man you are forcing into fellatio. (You might also irrumate a woman or a boy, but in written records, adult men are usually the target.) Where we today would very likely use some form of

fuck

to threaten or insult someone, Romans would have used

irrumare

. (We do have the option of

suck my dick

, but in English this lacks the connotations of violence and domination carried by the Latin word. It is more of an obnoxious invitation, less of a threat.) There’s a graffito in Ostia, a port town near Rome, that uses

irrumo

this way. It appears in a room that scholars think was a

taberna

(a small shop that sold drinks and food) in ancient times, whose owners made the interesting aesthetic choice to decorate with a bathroom theme: on the walls were paintings of people on latrines, accompanied by slogans such as “Push hard, you’ll be finished more quickly.” One of these slogans is

Bene caca

et irrumo medicos

—“Shit well and fuck [irrumate] the doctors.”

The poet Catullus assails some of his critics with

irrumo

too. Catullus was accused of effeminacy because he wrote about dalliances

with women, the delights of long afternoons spent in bed, rather than about war or farming like the more manly Virgil. He asserts his impugned masculinity with a verbal attack,

beginning one poem

:

Pedicabo ego vos et irrumabo

, “I will bugger you and make you suck me.” Threatening to stick his penis into the assholes and mouths of other men is supposed to prove that he is a

real

man. Displaying too much interest in sex with women, in contrast, is what got him accused of effeminacy in the first place.