Homing

Authors: Elswyth Thane

ELSWYTH THANE

- Title Page

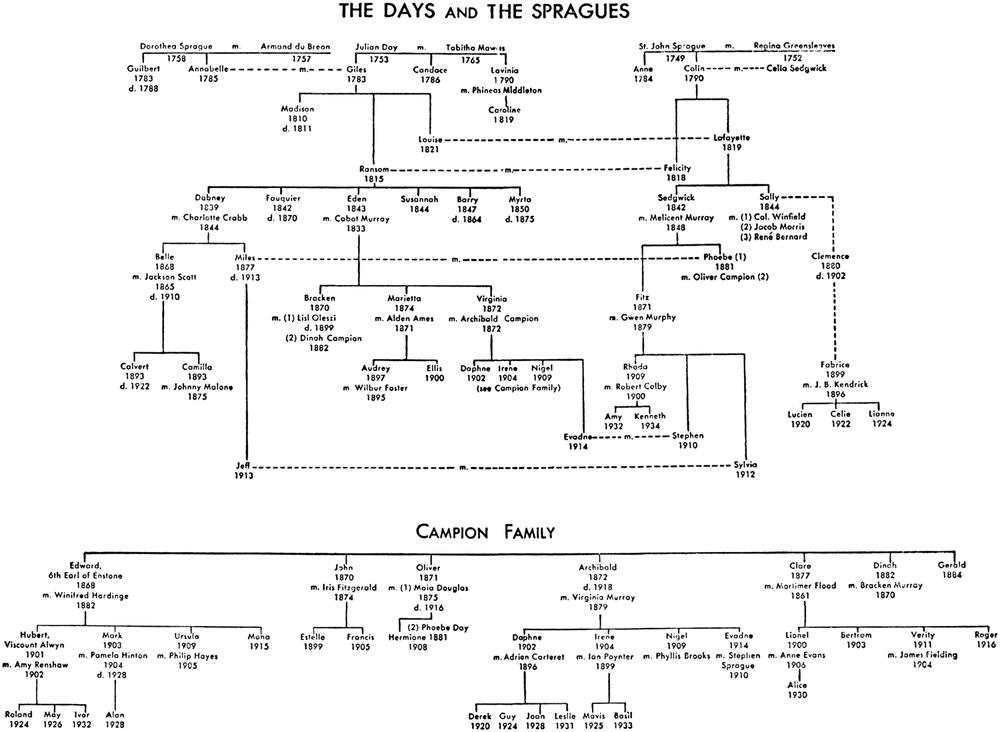

- THE DAYS

AND

THE SPRAGUES - ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- I.

Christmas at Williamsburg. 1938 - II.

Summer in London. 1939 - III.

Christmas at Farthingale. 1939 - IV.

Whitsun at Farthingale. 1940 - V.

Autumn in London. 1940 - VI.

Christmas at Farthingale. 1940 - VII.

Spring in London. 1941 - VIII.

Spring in Williamsburg. 1941 - About this Book

- Other titles in the series

- Copyright

I am again grateful to many people in England who have gone to a great deal of trouble to answer questions regarding details of the war years and to send me notes and publications which were not available here; in particular, Derrick de Marney, Daphne Heard, Mary Clarke, Christine de Stadler, and

Lt.-Colonel

W. E. G. Ord-Statter. Alice Grant Rosman, whose enchanting book,

Nine

Lives,

gives many a clue on the Animal A.R.P., put me in touch with M. O. Larwood of the National Register of Animals Service, who was most helpful, as was the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and Mr. Carpmael of the Blue Cross, concerning an almost

forgotten

aspect of the blitz. The British Information Services rendered their usual prompt assistance. Miss Susan Armstrong of Colonial Williamsburg supplied maps and information. The chronological sequence and news details were drawn from my own extensive files of the British weekly periodicals and

newspapers

, for the war years.

E. T.

1957

“

Y

OU

scared?” Stephen suggested, glancing at her

speechlessness

and then attending again to the road ahead of the car.

Evadne smiled, and leaned a little towards him—an

instinctive

nestling movement which acknowledged her need of reassurance.

“I wouldn’t have been a good pioneer woman,” she

murmured

. “Every shadow would have been an Indian, every twig would have sounded like a rifle shot. I would have woken up screaming with nightmares about being scalped. Just think if those trees came right in on a narrow trail—just think if we were in a covered wagon with arrows zinging past our ears!”

“Honey, you’ve got it all wrong. No covered wagons in Virginia—that was Death Valley. I thought you’d like this road—there’s a sort of Feel to it, I always think.”

“You mean there’s another road?”

“Yes, the main highway’s over there. We always take this one, along the River.”

“Because of the Feel.”

“Mm-hm.”

It was the back way to Williamsburg, running behind the big houses which faced the East bank of the James. As the day drew in, the trees either side of the road stood tall and aloof, cutting off the setting sun, too close together to allow more than a suspicion of the river on the right. Little dusty lanes led off at angles, with obscure, tipsy signs. Almost uninhabited crossroads

occurred

at long intervals. You met nothing coming the other way. Very different from Highway 60.

But she had surprised him again, because it was not the kind of scare he had had in mind. They had been married about three months ago in London, and he was bringing her home for a Southern Christmas with his family. And now his English

bride’s shyness of the first meeting with his parents was

overlaid

by her reaction to a back road at dusk in Virginia—an intuitive awareness of a wilderness which no longer existed.

He touched a button on the dashboard and their lights came on, barely visible yet in the waning daylight.

“That better? You want a drink maybe. That’ll pull

civilization

towards you.”

“I suppose they came this way on horseback,” she brooded. “With nothing but a sword.”

Again Stephen glanced at her over the wheel. Last September she was taking her First Aid and Air Raid Warden training in London for a Hitler war, while his own stomach fluttered fussily at what she must encounter during the course. Last September he had worked beside her in a dimly lit parish school while she fitted gasmasks on tense, well-behaved children and anxious,

well-behaved

old ladies, and her tact and composure had never wavered. He had listened and cued her while she recited to him the varieties of poison gas, their effects, and their detection—and her voice was as steady as though it read a bus schedule. The war hadn’t happened after all. Not yet. But now she jibbed at a shadowy road beside the River James. Women.

“They came this way for picnics,” he said cheerfully, and slowed the car as it emerged into a clearing with a grassy lane running off to the right. “That’s the road to Jamestown. There’s a museum there now, and a stone wall to keep the river from eating up the site of the town entirely. The old brick church is there still, what’s left of it, and the tombs—”

“Picnics at Jamestown,” she said thoughtfully, while the car slid on towards Williamsburg. “Amongst the tombs. I’m so ignorant. Who’s buried there? What’s Jamestown?”

“My dear girl!” said Stephen, registering marked horror. “Never let them hear you say

that!

How would you feel if I said, ‘Dover? Never heard of it!’”

“You’ll have to coach me,” she said comfortably.

“I should think so. Grandfather Julian won’t rest.”

“Oh, I do know something about him, vaguely. He was a Day, like Jeff, and his portrait hangs over the mantelpiece in Jeff’s house here in Williamsburg.”

“It’s in the front bedroom upstairs, as a matter of fact.”

“He came out from England while it was still colonies here didn’t he? Where do we come in—the Spragues, I mean?”

“The Spragues were here when he arrived,” said Stephen with some pride.

“The First Families.”

“Absolutely. Grandfather Julian Day and Grandfather St. John Sprague both fought in the Revolution—which you may have heard about too, vaguely,” said Stephen.

“Now I suppose we’ve come to Yorktown,” said English Evadne. “Go on. The British got beaten. For once.”

“Well, that depends how you look at it,” Stephen conceded cautiously. “The colonists were mostly British too. And half the British Army was German troops.”

“Oh. And the French, who turned up somewhere?”

“Yes, the French were in at the kill, on our side. But they weren’t at Valley Forge. Did you ever hear of Valley Forge?”

“Where’s that?” Evadne asked, and laughed, and nestled closer. “It was something about George Washington,” she

decided

shamelessly. “I’ll read up on it, truly I will. It’s really a new world for me, don’t forget. I never had any idea I’d come here.”

“Well, I warned you,” he reminded her, in view of his two years’ resolute courtship.

He drove on, reflecting happily on the baffling, delightful creature he had married. A year ago she would have stammered and apologized for her ignorance of Jamestown and Valley Forge, in the maddening state of humble anxiety to please everyone in which she had then existed. A year ago she would have been in a pitiable twitter of nerves for fear his people might not like her as his wife. But now Evadne had changed. Almost overnight she had changed from a defensive,

apprehensive

, intense young woman who always tried much too hard, into this incandescent, philosophical bride who never seemed to worry much about anything any more. It was a miracle. And it was

his

miracle. He, Stephen, had taught her to laugh at

herself

—and at him—after demonstrating to her with colossal patience and wisdom that nothing would induce him to think otherwise than idolatrously of her. And now here she was, on the way to Williamsburg with him, home for Christmas.

It came of so much love, he thought, the wheel under his hands, his eyes on the road. Nothing evil or unhappy could endure against love like his for Evadne. Since that first time he saw her in the lobby at the Savoy in London, not knowing who she was, not having the faintest idea that they were bound for the same party and were linked by distant cousinship. A hell of a

thing, he had thought more than once since then, if she hadn’t got out of the lift at the same floor he meant to, and preceded him to the same door—she thought by then he was following her, and slew him with a glance—and then, when he made himself known, “Welcome to London, Stephen,” she said, with her radiant smile, and he had kissed her, because after all they were kissing kin….

“What are you thinking?” she asked, noticing his silence.

“Why?”

“You’ve got the most

idiot

grin on!”

It broadened.

“I was thinking about the Savoy—that first night we met.”

“Bracken’s party. How long ago it seems now!”

“You came marching into the lobby and pressed the bell for the lift, remember? I had already rung for the lift, or I wouldn’t have been standing there, would I? But you bustle up, smelling of flowers, and press the bell. And I thought,

Women.

And then I took another look and it was all over with me,

boom!

I haven’t been able to see straight ever since.”

“I didn’t know what to make of you that night.” They had been over it before, but it never palled. Discovery. Always a fresh marvel of discovery, with him so sure from the beginning, and herself so unaware, so obtuse, and so misguided. “You went so fast,” she mused, as she had done before. “But how you could fall in love with anybody so

hopeless

as I was then—”

“You were hopeless,” he agreed. “And lost—and off on the wrong foot. But you didn’t know. That was the hard part. You didn’t know

from

nothing.

I just go on thanking God it was me that came along in time!”

“I gave you a bad run, didn’t I, Stephen?”

“Talk about wake up screaming!” He held out his right hand from the wheel, palm up, and she laid her left in it, warmly. “It will be years before I can be sure, in the dark, that you’ll be there if I put out my hand—”

“It’s all right, Stephen.” Her tone was motherly. “You’re in for it now. You’ll never be rid of me now.”

“For better, for worse.”

“Till death do us part,” said Evadne, and their fingers tightened with a swift, unspoken memory of last September’s portent, and the gasmasks and the shelter trenches scarring the green turf of London’s parks.

In the Sprague parlour at Williamsburg, the new song trickled lightly from Fitz’s fingers on the keyboard. Its lyric was lost in the muted whistle which carried the air, but it was a song about love at first sight—love for a stranger. Fitz had written it as a Christmas present for his son Stephen’s English bride, and around it, eventually, the next Sprague musical comedy would be written. They were a team now—father and son—music and lyrics by Fitz, dancing and singing (he called it singing) by Stephen.

The girl had finally stopped her nonsense and married him, when they had all begun to think she never would. Until

recently

there had been very little to recommend English Evadne to Stephen’s parents, but now they would see what they would see. Stephen’s mother, who had herself once come to

Williamsburg

a stranger-bride, was sure Stephen knew what he was about. And Fitz, remembering his own sensations when he had faced his redoubtable father that day, was determined to

welcome

Stephen’s choice as generously as the family received the unknown girl he himself had brought home almost forty years ago.

“I hope she won’t be nervous,” Gwen said from where she sat knitting by the fire following his thoughts as she often seemed to do, even in their silence. “I was terrified, the day I came. Of course it’s not quite the same.”

Their eyes met, amused and rueful, across the room. Instead of replying, he changed the music smoothly, so that the new song ran into an old one, one of his oldest, and Gwen began to sing it softly, watching him from where she sat.

“Ef de sun set red on a weary day,

De skies will clear ef de mornin’s grey,

An’ dat’s what I hope foh me—

Ma shadow gittin’ longer crost de grass,

Cool ob de ebenin’ done come at las’,

De sun goin’ down on me….”

“It’s

still

a good song,” he admitted judicially, and, “It takes you back,” said Gwen, resuming her knitting with a sigh.

Back to the time when he was a cub reporter on Cabot Murray’s newspaper in New York, and she was a frightened girl

singing in a third-rate music hall—you couldn’t blame the family for not knowing quite what to expect when he married her. They soon found out about that, though. Gwen had no tall ideas about a career on the stage, even after his musical comedies caught on and became almost annual fixtures on Broadway. Gwen only wanted to stay at home and raise babies, while the shows went on without her.

Baby Stephen grew up stage-struck and starred in the shows, with his sister Sylvia as his dancing partner. During the London engagement of the last show but one he had fallen in love with Evadne the Problem Child. But it wasn’t quite the same, no. The singing waif from the wrong side of the tracks which was the young Gwen, craving love and security—and this well brought up, protected Evadne, labouring under a Joan of Arc complex which had found more than one embarrassing outlet. She had kept Stephen dangling till everyone on both sides of the Atlantic wanted to shoot her, and then quite suddenly she had learned her lesson and began to eat out of his hand. Got it all out of her system, the family said in England, with visible relief. Grew up. Saw the light. Stopped being a crusader in lost causes. Fell in love. And about time too. Nevertheless in Williamsburg there was still the shadow of a doubt, and some suspense, for while Evadne’s mother was Fitz’s first cousin, Virginia had married abroad and her children were strangers to their American kin.

Stephen had got her at last, though. And because something had gone wrong with his left foot which hampered his dancing, he had closed the show in London and was bringing her home for Christmas. The song was ready for them, and for the new show. Even if Hitler started a war in Europe, Fitz was hoping they could still open a new show in New York. The shows always opened in New York and went to England after the American run.

“There was a war coming up then too—when I came here the first time,” said Gwen, abreast of his unspoken thoughts from across the room.

“Little bitty Richard Harding Davis kind of war,” he agreed, still playing. “It wouldn’t count nowadays.”

“You and Bracken almost died of it.”

“Almost. They do it better now. We were a bunch of amateurs.”

Cuba, it was that time. He and his Cousin Bracken Murray had gone out as field correspondents for the newspaper—but

that didn’t mean they didn’t get shot at, and Fitz had so far

forgotten

himself as to acquire a rifle and shoot back, though that was against the rules for correspondents.

Bracken was running the paper himself now, since his father’s death. But for Fitz the youthful fling at journalism was only an interlude in his music. He had come back from Cuba full of malaria and tunes, to his piano and Gwen, and had settled down in the big white house in Williamsburg where his father and grandfathers had lived, just across the little town from the big white house where the Day cousins had always lived. Bracken’s father, who was a Yankee, had married Eden Day. Fitz’s own grandfather had married a Day, his sister Phoebe’s first husband was a Day, and his daughter Sylvia had married a Day. The lines of cousinship were entwined and entangled for generations.

“There aren’t so many of us around here any more,” said Gwen, with her effortless clairvoyance. “When you brought me home to meet the family there must have been—well, it felt like

dozens!

Now there’s just us. It will seem kind of quiet to her, maybe. The children of the family are mostly in England now, on Virginia’s side.”