Honor Thy Father (34 page)

Authors: Gay Talese

Later in the day, after the men had left and while Rosalie was shopping, Bill decided to find out. Opening the patio door, he called to his eleven-year-old son Charles, who was building a new rabbit cage out of orange crates and chicken wire. Charles was constantly improving his skills as a carpenter and maintenance man; he was the one who fixed the flat tires on the bicycles, tightened the loose wheels of Felippa’s toy baby carriage, mowed the lawn and uprooted the weeds. With the Blue Chip trading stamps that he received from his mother and his aunt Catherine, he was saving toward an electric lawnmower, planning to earn extra money by tending to neighbors’ lawns. Although Charles was a year older than his classmates in the fourth grade, having been left back once in Long Island, he seemed neither embarrassed nor contrite when he brought home his latest unimpressive report card for Rosalie to sign. He possessed almost no competitive spirit as a student, caring mainly about things for which he would not be tested or graded. He was interested in animals, birds, and the insects that he was endlessly catching. He was always polite and patient; and though he was the adopted child and was aware of it, he was the one who seemed most at home in the Bonanno household.

When he heard his father calling him, Charles did not frown or fret as his brothers might have done; he came immediately, followed his father into the television room and remained standing as his father closed the door. Tall and thin, with green eyes and a lighter complexion than his brothers, Charles’s gentle good looks were not marred by the fact that his upper left eyelid drooped slightly, a congenital defect that did not impair his vision and that a doctor said could easily be corrected with minor surgery when the boy was older.

Bill sat down in a black Barcalounger against the wall, looked at Charles, whom he called Chuckie, and asked: “Chuckie, do you know what I do for a living?”

“No,” the boy said, seeming slightly confused but not upset.

“Does your teacher ever ask you what I do for a living?”

“No,” said Charles.

“Do you ever wonder yourself?”

“No,” Charles said, casually.

“You don’t give a darn, do you?” Bill asked, lightly.

Charles paused, then said, “Well, in New York you used to work in a hardware store.”

“A

hardware

store!” Bill repeated.

“Well, didn’t you?”

“Don’t you mean a

warehouse?

” Bill asked.

“Oh, yes, that’s what I mean, a warehouse.”

“Suppose one of your teachers or someone you know at Cub Scouts asks, ‘What does your father do all day?’ What would you answer?”

“I’d say that he sits around and watches TV.”

Bill smiled. Then he asked, “Do you remember Uncle Hank?” referring to the late Sam (Hank) Perrone.

Charles nodded, and Bill asked, “What did he do for a living?”

“I forget.”

“You’re not a very cooperative witness,” Bill said, raising an eyebrow in mock disapproval. Then Bill continued, “Suppose your scoutmaster asks you a direct question, Chuckie, wanting to know what I do—what would you tell him?”

“I wouldn’t tell him anything.”

“Why?”

“Because I don’t know what you do.”

“Why don’t you know?”

“You never told me.”

“What about money—if you had none, wouldn’t you be worried?”

“Yes, kind of.”

“But you think I have money, don’t you?”

“Yes.”

“How do you know?”

“Because lots of times, when I go in your room with mommy, I see a lot of money.”

“You do?” Bill asked, surprised. “Where?”

“On your bureau.”

“A lot of money?”

“Sure. Quarters, dimes, I’ve even seen ajar full of coins.”

“You think that’s a lot of money?”

“Sure,” Charles said, adding, “and you said you were going to buy me some big cages for more rabbits….”

“Next witness,” Bill interrupted, telling Charles to send in Joseph.

Joseph was thin and frail, had large brown eyes and long lashes. He was competitive by nature and there would have probably been continuous discord between Joseph and his older brother if Charles were less conciliatory. The fact that Joseph was so often ill with asthma and unable to exert himself physically influenced their relationship, and much of Joseph’s discontent was no doubt attributable to the frustration of having to gasp for each breath.

But despite Joseph’s condition and his frequent absences from school, he seemed to have no difficulty in keeping up with his class. He read constantly when confined to bed, and he spent hours working on crossword puzzles. He was curious and aware and had already expressed confusion about Bill’s unusual business hours and unpredictable routine. Joseph had not yet asked direct questions about it, but Bill suspected that when the time came for him to explain his way of life, Joseph would have already figured it out; and Bill wondered at this moment whether it was desirable to pursue this little game with his most sensitive son, who now stood before him, unsmiling. Bill decided to proceed with caution.

“What grade are you in, Joey?” Bill asked.

“Third.”

“Do your teachers ever ask what I do?”

“Yes,” he said.

Bill hesitated for a moment; but then he went on, “What do you tell them?”

“Mom once told me you were in the trucking business,” Joseph said. “That’s what I tell them.”

“What do you mean by trucking business—do you know what I do?”

“You drive around, I guess.”

“Did you ever see me in a truck driving around?”

“No,” Joseph answered, “but Tory said once you gave him a ride in a truck.”

“Yes, that’s true,” Bill said. “We went to the warehouse one day. But what do I do now?”

“I don’t know,” Joseph said, slowly, seeming suddenly tense. “But I know you’re not in the trucking business.”

Bill looked at Joseph standing uncomfortably in the middle of the room. Bill stopped the questioning. He was sorry he had indulged his curiosity in this manner, but decided to finish what he had started with his children as hastily as he could. Abruptly thanking Joseph, he asked that Tory be sent in.

Tory, six years old, had a round angelic face and bright brown eyes, and of the four Bonanno children he was clearly the most personable and entertaining. He was also clever, and he could worm his way out of punishment he deserved by offering ridiculous, funny excuses. One recent evening after supper, Tory asked his mother if he could go outside and play, to which Rosalie replied, sharply, “It’s seven o’clock!” Later, after Rosalie caught a glimpse of Tory playing on the sidewalk with other boys and rushed out to grab him and scold him for disobeying her, he pleaded innocently, “But you didn’t say I couldn’t go out—you just told me what time it was!”

Tory was also skillful at finding loopholes in the family rules that were an attempt to regulate his rough behavior toward Felippa, who was one year younger and was constantly provoking him, secure in her knowledge that her father had warned Tory against ever laying a hand on her. Invariably, on leaving the house for an overnight trip, Bill would remind Tory: “Now remember, I don’t want you to be hitting your sister while I’m away,” and Tory would usually nod in agreement. But a few weeks ago, shortly after Bill returned from a weekend out of town, he saw Tory swatting Felippa on the head because she had deliberately scribbled across his coloring book. Bill grabbed Tory, but before Bill could say anything, Tory blurted out his explanation: “You said I couldn’t hit her when you were away—well,

now

you’re home.”

As Tory walked into the room wearing a football helmet, with dirt on his face, Bill was reminded of the comic strip character Sluggo. Bill smiled and asked: “Tory, did anybody ever ask you what I do for a living?”

“No,” Tory said.

“Did you ever think of what kind of work I do?”

“No.”

“Do you remember Uncle Hank?”

“Yes.”

“What kind of work did he do?”

“I don’t know.”

“Don’t you remember the warehouse?”

“Oh, yeah.”

Tory started to pick his nose, and Bill told him to stop it, to stand up straight.

“You remember the trucks, don’t you?”

“Yes,” Tory said.

“Remember when we took a ride?”

Tory nodded.

“Well, where do you think Daddy gets his money from?”

“People give it to you.”

“Do people give you money?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

Tory shrugged, nonchalantly.

“Suppose your teacher asked you what your Daddy did—what would you answer?”

“I’d say I didn’t know.”

“Right.” Bill said. “Now send in your sister.”

Felippa, who is called Gigi around the house, walked in carrying a doll. Her reddish brown hair was cut in bangs, she wore small gold earrings, and she was very self-assured. She seemed to know, even at the age of five, that there was nothing her father would not do for her. If she was spoiled, and there was little evidence to refute it, Bill held himself completely responsible, and he would have it no other way. He was totally enchanted with her and he knew that what he would most miss about home—if he had to face a long stretch in jail—would be the uncritical acclaim he always received from his daughter.

“Gigi,” he began, “do you know what Daddy does for work?”

“Yes,” she said, smiling.

“What?”

“I don’t know,” she said, starting to giggle.

“Where do I get my money from?”

“From a man.”

“Which man?”

“I don’t know.” She giggled again.

“Remember Uncle Hank?”

“Yes.”

“What kind of work did he do?”

“I don’t know,” she said, and when Bill laughed, she laughed too, running into his arms, and as he hugged her he announced, “Court is adjourned.”

Joseph Bonanno, 1941

Salvatore Bonanno, father of Joseph Bonanno, 1890

Joseph Bonanno, age 5, 1910

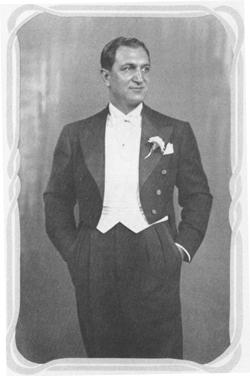

Joseph Bonanno, is in Brooklyn, 1926