Horror in the East: Japan and the Atrocities of World War II (10 page)

Read Horror in the East: Japan and the Atrocities of World War II Online

Authors: Laurence Rees

If Pearl Harbor was a shock to the Americans, it was by no means an unqualified success for the Japanese.

Whilst many of the US battleships were damaged or sunk, the aircraft carriers completely escaped damage since they were at sea on exercise.

The carriers had been the key Japanese target — the battleships posed little military threat because they did not have the speed to accompany a carrier task force.

As a result, the Japanese attack merely eliminated warships best suited to action in the last war rather than in the coming one.

Had the Japanese managed to destroy the land base at Pearl Harbor that might have been a serious blow to the Americans, but Admiral Nagumo, commander of the Japanese task force, broke off the attack early, fearful of the return of the missing carriers.

At Pearl Harbor the Japanese did not destroy the American Pacific fleet as they hoped, nor did they break President Roosevelt’s reputation and lay the ground for a compromise peace.

Equally, contrary to Japanese expectation, the skill with which the Imperial Navy had conducted the raid on Pearl Harbor did not make Americans like Gene La Roque respect their adversary more — it had quite the reverse effect and confirmed the American prejudice that the Japanese were not just ‘sneaky’ but scarcely human: ‘One has to keep in mind, I do believe, that we had been taught that the Japanese were subhuman when we got into the attack.

Of course we had no love for Hitler or the Nazis, but we also had many people in America who were of German descent or of Italian descent.

It was an entirely different view we had of the Italians and the Germans than we had of the Japanese.

We knew the Japanese were sort of subhuman.

We thought they were.’

Just five hours after they began bombing Pearl Harbor, the Japanese attacked the British colony of Hong Kong.

Surrounded as the British forces were by the Imperial Navy at sea and the Imperial Army across the border in China it had long been accepted that, as Churchill put it, ‘There is not the slightest chance of holding Hong Kong or relieving it.’

16

None the less, the British war cabinet expected the colony to hold out against the Japanese for at least several weeks.

But, like the Americans, the British had grossly underestimated Japanese military power.

’First of all we thought they were American planes,’ says Connie Sully, then a nurse at the makeshift hospital at Hong Kong’s Happy Valley racecourse, as she saw aircraft swoop down from the sky.

‘And then, of course, we saw the great sun on them and then we realized.’

Just as at Pearl Harbor, those under attack formed the immediate view that their enemy was dishonourable.

‘The next thing there were bullets coming out of the wings.

We had three Red Crosses on the top of the jockey club, so they could see that — but they never worried about that.

Didn’t mean anything to them.

And I knew from the other places in China they’d also bombed that you couldn’t expect any sympathy from them.’

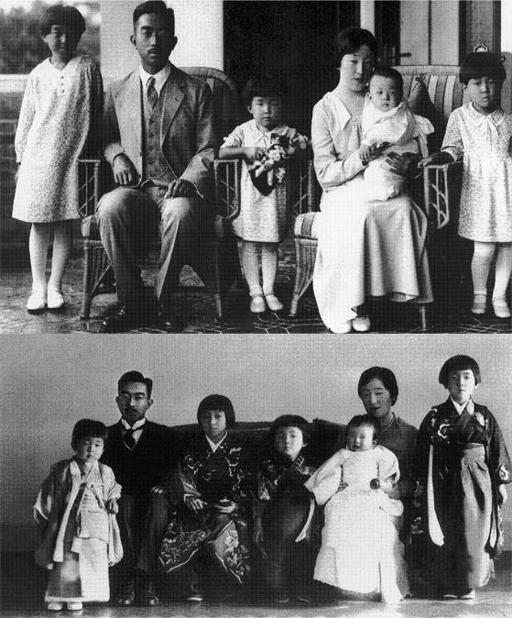

Above

The two sides of Emperor Hirohito and the rest of the Japanese royal family: the modern, Western-dressed family group (top) and the family in traditional dress (bottom), harking back to the era before any real Western contact.

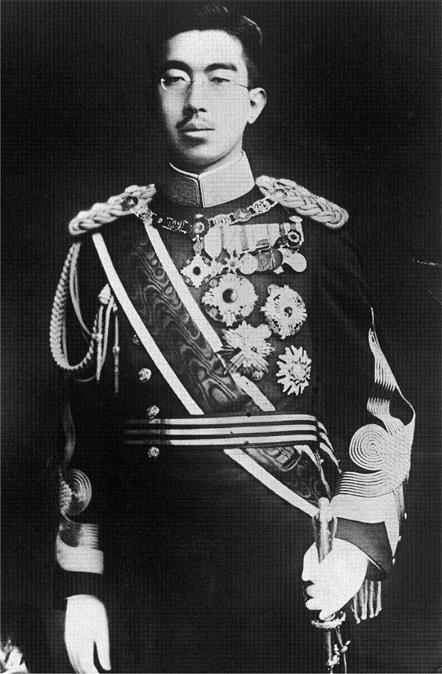

Above

A formal picture of Emperor Hirohito taken in 1933 when he was 32 years old.

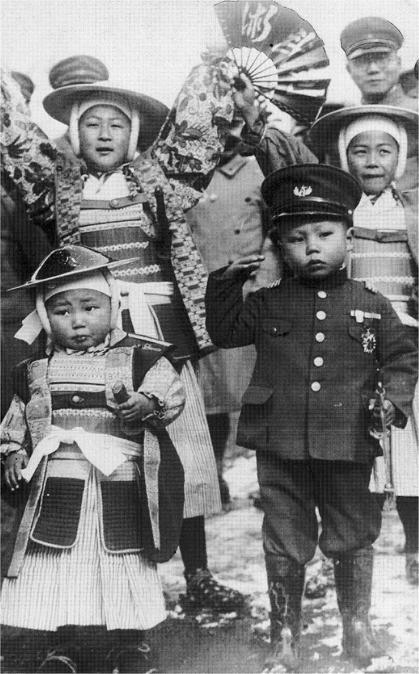

Opposite

Militarism ancient and modern: boys in samurai dress (left) and army uniform (right).

Above

An early taste of the destruction modern aerial weapons of war would cause.

Shanghai railway station after the Japanese had bombed it in 1937.

Opposite top

Not the French Riviera but the beaches of Japan — holidaymakers in 1930 when it was still acceptable to partake of Western-style enjoyment.

Opposite below

A crowd of 80,000 assemble in Tokyo to celebrate the first anniversary of the signing of the Anti-Comintern Pact in 1937.

Four years before Pearl Harbor, the flags of Nazi Germany, Japan and Fascist Italy hang together for all to see.

Above

Two scenes of destruction and suffering from the Japanese war against China.

No

one knows exactly how many civilians the Japanese killed — but at least several million died.

Opposite

Two of the sadistic ways in which the Imperial Army dealt with Chinese prisoners:

burying them alive (top) and killing them in bayonet practice (bottom).

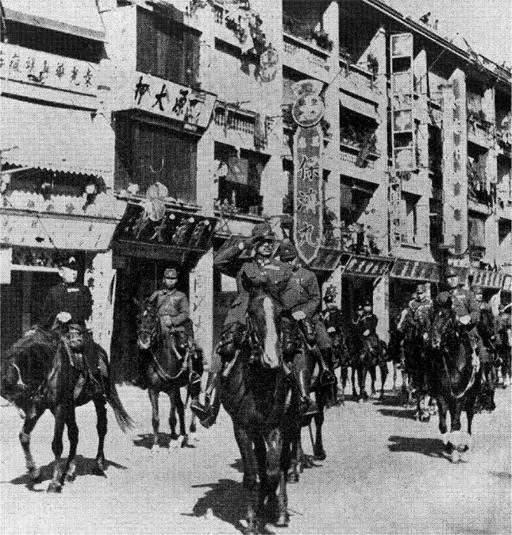

Above

Lieutenant-General Takashi Sakai enters Hong Kong and salutes as the victorious

commander less than a month after the attack on Pearl Harbor, which began the war against the Western allies.

This moment was, along with the fall of Singapore just weeks later, the high point of Japanese military fortunes.

The Japanese eliminated what little hope the colony had of air defence when they destroyed the handful of RAF planes based at Kai Tak airfield before they left the ground.

Japanese troops, many from the 38th division and battle-hardened from the conflict in China, made strong early advances towards Hong Kong island after crossing the Sam Chun River into the New Territories.

By 13 December the British forces, outnumbered and with no hope of reinforcement, had withdrawn from the mainland to defend Hong Kong island itself.

The Japanese bombarded the island before successfully landing troops on the 18th.

Once the Imperial Army had established a firm beach-head they fought their way inland, arriving at the British army medical store at the Silesian mission in the centre of the island on the 19th.

Osler Thomas, then a volunteer medical officer with the 4th battery, had spent the night at the mission and had just left to drive back to his unit when he was shot at by the Japanese.

He retreated to the mission and from the top windows he and his comrades — a handful of fellow members of the Army Medical Corps — realized that they were both surrounded and outnumbered.

‘We were not meant to fight,’ says Osler Thomas.

‘We were medical personnel, not fighting soldiers.’

As a consequence they gave themselves up.

‘And it wasn’t very long afterwards that the Japanese knocked at the doors and ordered us all out into the courtyard.

We went out and the women were separated to one side and the men to the other side.

All the men were dressed in khaki, so that there was no distinction between military personnel and civilians.

The Japanese then ordered all the men to be stripped from the waist up except for the two of us — officers who were allowed to keep our jackets on.’

Of the thirty-three men assembled in the courtyard by the Japanese the majority were civilians; only a handful were army medical orderlies.

But these soldiers of the Imperial Army were not concerned about the combatant status of their captives.

All the men — civilians as well as soldiers — were ordered to climb the steep steps at the back of the mission until they reached a storm water drain, known by the Indian word

nullah

, which flowed along the side of the hill.

Above them on the hillside, looking down at them as they stood alongside the nullah, were jeering Japanese troops who had gathered to watch.