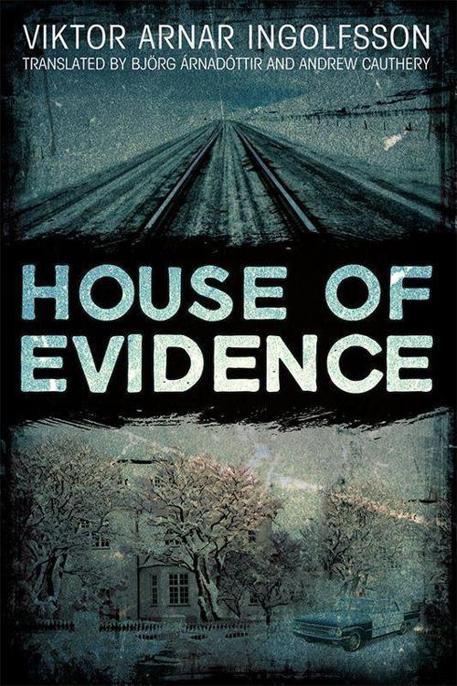

House of Evidence

Authors: Viktor Arnar Ingolfsson

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #General, #Police Procedural

Also by Viktor Arnar Ingolfsson

The Flatey Enigma

Daybreak

(forthcoming)

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Text copyright © 1998 by Viktor Arnar Ingolfsson

English translation copyright © 2012 by Björg Árnadóttir and Andrew Cauthery

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

House of Evidence

was first published in 1998 by Forlagid as

Engin spor

. Translated from Icelandic by Björg Árnadóttir and Andrew Cauthery. Published in English by AmazonCrossing in 2012.

Published by AmazonCrossing

P.O. Box 400818

Las Vegas, NV 89140

ISBN-13: 9781611090994

ISBN-10: 1611090997

eISBN: 978-1-6110-9099-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012913725

This book is dedicated to the memory of my stepfather and friend, engineer Sigfús Örn Sigfússon, who practiced his profession on four continents.

Iceland’s first and only railway was built in Reykjavik in 1913, with two locomotives running between Öskjuhlíd and the shore (a distance of two miles), conveying materials for construction projects at Reykjavik harbor from 1913 through 1917. It was decommissioned in 1928, and the last tracks were removed during the Second World War.

—

The Icelandic Encyclopedia

, Volume 2, page 199

FAMILY TREE AS RECORDED BY JACOB KIELER, HISTORIAN

S

he took the diaries from the box and laid them out on her small desk. There were twelve old, worn books, varying somewhat in design but all of a similar size—four to five inches wide and around seven inches high. Each book contained at least two hundred pages, though the precise number varied. The paper was on the whole thick and of good quality, with well-spaced rulings; the bindings were superior, sturdy. Twelve books—and there were more, she knew that.

Most of the diary entries were short and mundane; descriptions of weather and the like, and she could skip these, but in between there were in-depth contemplations where one day might stretch over several pages. She would have to read these parts thoroughly. Perhaps she might find something that could give a clue to the reasons for the diarist’s fate; it was a faint hope, but worth pursuing.

She picked up the first book. The handwriting was clear and easy to decipher.

She read well into the night that first day, and over the days that followed, she usually had two or three books in her bag, using every available moment to leaf through them.

Diary I

June 30, 1910. Today I graduated from high school. After the ceremony at the school, there was a coffee party on the lawn in front of the new house my father is having built on his lot next to Laufástún. Father gave me this book and suggested I should keep a diary. “There may come a time in your life when such a thing will prove very useful,” he said in the speech he gave in my honor. I shall try and follow his advice, but I stared at this sheet for a long time before putting pen to paper. How am I going to approach this task? Each written word is there to stay and I must, therefore, think and plan the sentences well. Perhaps that is the first lesson he hopes this task will teach me…

H

e no longer felt pain.

Forty-eight-year-old Jacob Kieler Junior sat, legs outstretched, on the floor in the main parlor of Birkihlíd, leaning crookedly against the doorpost that led to the lobby. The wound in his chest bled incessantly. His gray knitted vest was soaked with the blood that poured down his body, forming a pool on the wood floor beneath him. When Jacob moved the hand he was leaning on and it landed in the blood, he looked down in surprise. His breath rattled, and bloodstained froth was forming at the corners of his mouth. His expressionless face had become white and his gray eyes were half-closed.

He had fallen off the chair when the shot hit him. The pain had been unbearable at first, but as he crawled toward the telephone in the lobby to call for help, he became numb and lost the power of his legs.

The parlor, where Jacob now found himself, was a large room, more than a thousand square feet, with a high ceiling. In the middle of the floor to his left were three large, heavy, leather settees; to his right a bay with tall French windows and long, heavy drapes. He examined the German chandelier as if seeing it for the first time. There were twenty-eight bulbs in all. They were arranged

in three wreaths, sixteen at the bottom, then eight, and finally four at the top. The light from each bulb was faint, allowing the chandelier’s skillful craftsmanship and gilding to show through.

He noticed the open office door at the far end of the parlor. The light had not been switched on in there, and intricate silhouettes appeared on the walls where the light from streetlamps and the night’s full moon shone through the windows between bare tree branches. Jacob could see the outline of the large desk in the pale light; it stood there, resolute, waiting patiently for a worthy master.

Through the office windows, he caught a glimpse of the house next door. It was completely dark and utterly silent.

Birkihlíd stands on a narrow street in Reykjavik’s old district, to the east of Hljómskáli Park. Early in the century, well-to-do citizens had built their mansions at a polite distance from each other, but more recent residents had added garages and other extensions so now it was all much more cramped. The road, which had originally been intended for pedestrians and horse carriages, had been made into a one-way street with closely packed parking bays on both sides. Trees had been planted next to the houses soon after they were built; they had thrived, growing over many decades, and now towered above the streetlamps. In the summer their leafy crowns obscured the houses and gardens, but at this time of year they stood bare.

Jacob looked through the open door into the dining room. The light was on in there, and he saw eleven high-backed chairs around the large table in the center. The twelfth chair was in the parlor, lying on its side in the middle of the floor. This bothered him. The chair should be in its place. Jacob tried to get to his feet. He wanted to put the chair back where it should be, but he had no feeling below his chest, and the only movement he could manage was a

feeble twitching of the shoulders. The large clock that hung from the dining room wall gave a single chime, indicating half past one.

There was a fireplace in the center of the wall to his left, its surround built of slabs of quarried dolerite, set into the wall. The hearth was large and deep, and the floor in front of it was tiled with the same stone as the surround. The fire had not been lit, and the ashes were cold.

A grand piano commanded the space to the left of the fireplace, while on the wall to the right was the portrait of his mother, painted when she was just eighteen years old. She sat straight as an arrow and gazed to one side, an inscrutable expression on her face. What would happen to this picture now, he suddenly wondered, but his thoughts came and went, and this one went without resolution.

He looked over his shoulder into the lobby. There was the telephone on the table, and a small calendar hanging on the wall above it. The year was 1973—Wednesday, January 17. Would anybody remember to change the date in the morning? No, it didn’t matter anymore.

His attention was drawn to the chandelier again. Now all the bulbs shone as one light that dimmed and brightened and then dimmed again. In his mind’s eye it changed into a globe that came closer and closer.

Outside it had begun to snow. The snowflakes were large and wet, and fell quickly to the ground in the still, dark night, as if the city was pulling a thick, white blanket over itself as it fell to sleep.

Diary I

June 30, 1910. While the visitors were staying with us, my father planted some birch trees along the boundary of the lot, and named the house Birkihlíd.

There are fifteen of us graduating from high school this time, the first ones under the new rules. Eight were external students…

July 1, 1910. The second day of this diary. I am still not sure how to proceed with making this record. It is probably best to let the mind decide, and write whatever is uppermost in my heart each time. I met with my fellow students and friends; we decided to take a trip north by boat to Akureyri, returning south by land…

July 2, 1910. Am getting used to the diary. It is probably best to write it while waiting for supper to be served. If something important happens after that, it can be added before retiring to bed. I cycled to Hafnarfjördur today…

July 4, 1910. I discussed my forthcoming studies with my father. He has not come to terms with my intention to become an engineer. I, on the other hand, am convinced that this is the right decision and am greatly looking forward to beginning my studies in Copenhagen this fall. I begin by reading propaedeutic at Copenhagen University while attending lessons in mathematics and physics at Polyteknisk Læreanstalt, and then start the engineering course the following fall, God willing…

July 5, 1910.

Vestri

set sail for Akureyri from the harbor at nine o’clock this morning with us companions on board. This is a decent boat, length 160 feet, beam 26 feet, and height 17 feet to the top deck. The first class has 40 passenger cabins, the second class 32. There is a lounge for ladies and a smoking salon for men on the top deck. 24 people can dine at the same time in the dining room. There are bathing cubicles and other amenities. Helgi is seasick…