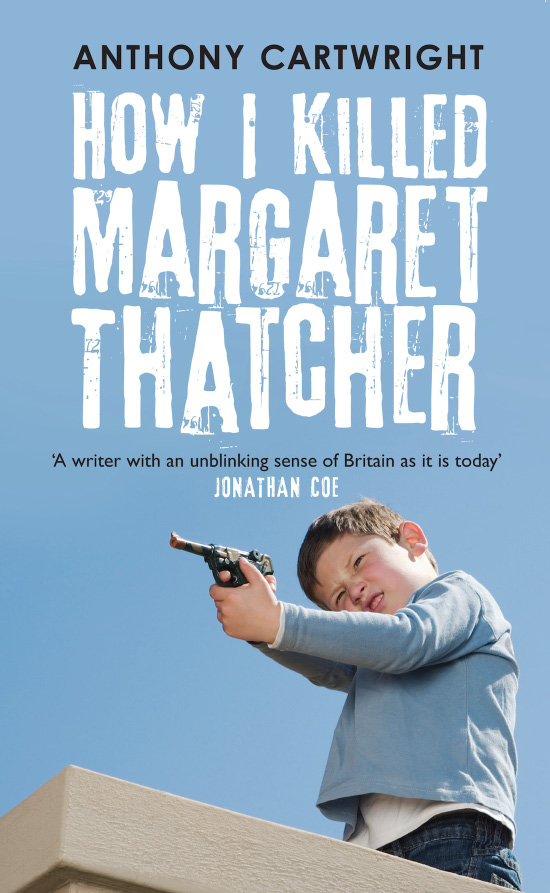

How I Killed Margaret Thatcher

Read How I Killed Margaret Thatcher Online

Authors: Anthony Cartwright

Tags: #Conservative, #labour, #tory, #1980s, #Dudley, #election, #political, #black country, #assassination

About the Author

Anthony Cartwright

was born in Dudley in

1973

. He lives in North London with his wife and son.

First published in 2012

by Tindal Street Press Ltd

217 The Custard Factory, Gibb Street, Birmingham, B9 4AA

www.tindalstreet.co.uk

Copyright © Anthony Cartwright 2012

The moral right of Anthony Cartwright to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without either prior permission in writing from the publisher or a licence, permitting restricted copying. In the United Kingdom such licences are issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP.

All the characters in this book are fictitious and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental

A CIP catalogue reference for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978 1 906994 35 8

eBook ISBN: 978 1 906994 91 4

Typesetting and eBook design by

Tetragon

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by CPI Mackays, Chatham, ME5 8TD

â

Judas Iscariot's here, look. Here comes Judas Iscariot.

My grandad says this as my uncle Eric walks up the path from the allotments. He smiles and it sounds like he's joking, but even from this distance I can see that my grandad's eyes are like the crocodile's at the zoo.

All right, Jack, Uncle Eric says and looks confused.

My grandad walks right up to him and says Judas again and then lamps Uncle Eric in the face and knocks him across the back steps. I have never seen anything like this before in my life. Last Sunday they had their arms around each other in the front room, singing I'll take you home again, Kathleen; now they're wrestling on the steps. I have never seen grown-ups have a fight, let alone my own grandad. He's fifty-six years old. My nan screams, so does my mum; so does Stella, my uncle Eric's daughter, and she tries to pull my grandad back. Uncle Eric is bigger and younger than my grandad; my nan says that when Uncle Eric wears his sunglasses at the caravans he looks like Roy Orbison.

My grandad is off him now, on his feet, out of breath. He points through the back gate and down the path through the allotments.

Never come here again. Never come to this house again. Dun yer hear me?

My grandad spits on the ground. My nan says his name, Jack, Jack, Jack. Stella looks at her broken fingernails. Uncle Eric scrambles up to his feet and goes back the way he came. My grandad points.

Dyer hear me, Judas?

I have never seen anything like this in my life.

She tried to kill me, after all. She tried to kill all of us. I nearly died on her first day as prime minister. I fell out of that back bedroom window at my nan and grandad's house just after the fight. I used to sit on the window ledge and look out across the allotments, at my grandad strolling between the pyramids built for runner beans and sweet peas and the bright coloured windmills that were meant to scare the birds; at Cleopatra, the Robertsons' sand-coloured cat, still as a sphinx on the fence, and at all the factories and works yards beyond. I lost my balance, tumbled off my perch, after the most incredible thing I had ever seen in my life; grunting and swearing, the radio playing at the same time, almost teatime; my mum sat at the kitchen table waiting for my dad to come back from work.

I flipped over in mid-air, saw all the chimneys in the distance, smoke dripping slowly into the sky; and then came upright, and then upside-down again, then halfway between. And that probably saved my life because I went arse-first through the shed roof, with a crash like a bomb going off.

I remember I thought I was dead. This is what it's like to be dead and gone, I thought, all the air knocked out of me, looking up at the outline I'd made in the roof, the shape of a nine-year-old boy, that I thought was maybe my soul ascending. Perhaps I didn't think that then, but I understood that when you died you left your body and went somewhere else and I thought I'd get to see my great-granny and my grandad's pet budgie, Jennie Lee. Jennie Lee was named after Nye Bevan's wife, my grandad would explain to people and watch for their reaction. He'd recently found her stiff and lifeless on the bottom of the birdcage. And although I realized I'd miss everyone, I supposed I'd see them all soon enough so it didn't matter that much.

In fact, I'd been saved by my own backside and a big pile of dust sheets left by the council after they'd decorated the downstairs room for my great-granny to stay in before she died.

When the air rushed back into my lungs, I let out a scream that my mum said later was exactly the same as the one I gave when I was born. My arse felt like it was on fire; my lungs like they were sucking in air from one of the furnaces that used to blink and glow out in the distance when it got dark.

My grandad thumped Uncle Eric because he voted for Margaret Thatcher and pretended not to have. I don't know how my grandad found out; voting's supposed to be secret. I hadn't even heard the name Margaret Thatcher until a few days ago and I'm already sick of it. I'm worried too because I know there's a bigger secret to come out. My dad voted for her as well. He voted Conservative, Tory, which is the same thing. I'm not meant to know but I overheard him tell my mum.

Oh, Francis. What yer done that for, yer saft devil? she asked him.

When she said that it wasn't like when she says it for things like when he's left wet towels lying on the floor or that time he gave a five pound note to Natalie Robertson when it was her birthday and my mum thought it was too much to give her; no, her voice was sad and heavy when she said it and I knew it was something bad.

My dad didn't say anything, shrugged his shoulders. He wasn't meant to have voted for her. My mum told him he was wrong, that he'd made a mistake and not to say anything else about it, for God's sake. We're all Labour. Our MP's Labour: my dad's vote didn't really count; or my uncle Eric's. They made a mistake, I suppose.

I supposed it then and I suppose it even more now. I worried about what would happen if my grandad ever found out about my dad, a worry that ebbed and flowed for years afterwards. It was only when it was too late that I realized we had other things to worry about.

My uncle Eric died a few years ago; he was on holiday in Benidorm and had a heart attack. They had to fly the body back. He and aunty Sheila were making plans to move out there. Eric had done all right for himself, set up a scaffolding firm, got a contract from the council. I went to the funeral. My grandad stayed at home, refused to come to his own brother's funeral. I sat in the car with Stella. She comes in the pub every few Sundays when we do a roast dinner. We never mention the feud.

There are faces above me, familiar and terrified, my mum and nan; Stella, whose mascara runs across her face as she cries; and my best mate, Little Ronnie Robertson, who has scrambled over the fence from next door at the sound of the crash, his glasses wonky like always. His sisters are in a line behind, all the way to their mum stood on the back step. They stand with their hands on their hips and in dresses and cardigans with their hair long and wavy, going up in two-year gaps; their mum on the step is an older version of them. If they walk through the town together you see people turn their heads to watch them. Ronnie looks like his dad. He's the runt of the litter.

Doh move him! my grandad shouts.

Oh Sean!

Oh darling!

Doh move him!

Oh Sean, darling, what have yer done?

I said doh move him, he might've bost his neck.

My grandad's face appears at the window, red and angry-looking. He pulls the sheeting back from the frame, popping rusty nails across the shed like gunshots.

His neck's bost!

A bosted neck!

News of my broken neck is passed back along the line of Robertson girls, and echoes back through my own family, and on down the street, and over Kates Hill and down through Cinderheath, through all of Dudley and on to Tipton and on across England.

I haven't broken my neck, I try to say, but I think maybe I've broken my arse.

If his neck's bost yow cor move him.

My mum starts to pull me up off the dust sheets.

His eyes am open, look yer.

My mum lets me drop back onto the dust sheets and crouches down next to me. Her hair brushes my face.

Sean, can yer hear me, darling? Iss all right, iss all right. Can yer squeeze me hand?

I squeeze her hand and then raise my arms. Ronnie puts his thumbs up and grins before his sisters whisk him away and my grandad mutters, Right as rain, and holds the fist he used to punch Uncle Eric out in front of him like a wounded paw.

My dad arrives from work during the commotion and carries me, on the dust sheets that saved my life, to the kitchen table to lie face down because I can't stand any pressure on my arse. He holds me to his chest, like I weigh nothing at all, that work smell on his open shirt, of soap suds and metal.

There is a debate about whether to go to hospital or not and how we should do it, everyone talking at once. My grandad's right hand is enormous, he can't drive; he holds a bag of frozen peas against it while we talk in the kitchen. He doesn't want to go to hospital, anyway.

I doh need to go to the hospital, sort Sean out, for God's sake.

Yer need that lookin at, my nan says to him. Doh say another word, Jack. Yow've said enough today.

We all go in my dad's car. My grandad sits in the passenger seat with his injured hand in front of him and I lie on my mum and nan across the back seat with my arse in the air. Stella's left to look for her dad.

The radio comes on as the engine starts; Margaret Thatcher's voice fills the car.

Turn her off, will yer, Francis? Her's caused enough trouble for one day.

Stop talking, Jack, my nan says.

Iss her bloody fault, I hear my grandad mutter under his breath.

We sit separately from my nan and grandad at the hospital. Uncle Eric and Stella arrive but they sit away from us too. Uncle Eric is also holding a bag of peas, wrapped in a tea towel, up to his eye. Grandad and Uncle Eric don't look at each other. I see my nan and Stella walk over to the middle of the room and start to talk and my nan puts her hand on Stella's shoulder before my name is called and I get taken through to see the doctor.

I get an X-ray and a lollipop. I have a bruised coccyx and buttocks and hundreds of splinters in my backside.

My mum bursts into tears for no reason when the doctor asks was no one watching me.

I want to say no one could have been watching me because they were all watching my grandad and Uncle Eric have a fight and, anyway, I'm nine years old so don't need watching, but I don't get to say anything. I start to speak but my dad says shush and looks at me and I know better than to say anything. The doctor starts to talk about some cream they have to rub into my backside to get the splinters out and stop infection.

My dad drives me and my mum to my nan and grandad's house. Then he goes back to hospital and gives Uncle Eric and Stella a lift home. Eric's okay; he has a black eye and a few loose teeth. They had to X-ray his eye socket. Then my dad brings my nan and grandad back to the house.

My grandad has broken some bones in his hand and it's bandaged up so it looks about ten times its normal size, like when someone is hurt in a cartoon. I can tell that my nan isn't speaking to my grandad. She stands next to him and stares into space with her lips tight together.

This is what yer needed, I bet, my mum says to my dad as they stand on the back step. Working all hours and now this.

My dad shrugs and smiles at her. Iss all right, he says.

She rubs his back. I bet yome shattered, she says.

I'm tired. I am tired, he says and nods.

This is better, much better, because last night I heard them talking late in the kitchen with the radio playing the election results.

You should be ashamed of yerself, she whispered. I am.

We've got to think about ourselves, my dad said. About us.

To think it, voting Tory.

You'll see. The country's got to change.

Doh say this to nobody else, Francis, will yer?

I ay that saft.

I doh know why yer did it. Yer doh even like politics.

Things am gonna change.

They can change for the worse, yer know, as well as the better.

Just wait and see, my dad says, yow'll see.

I cor see that yome the same person I married. I doh know what's got into yer.

When she said this, my mum walked out of the kitchen to come and turn the hall light off and I had to scramble up the stairs and into bed.

There is the crash of metal somewhere from the works across the allotments.

Dyer think Stella got her broken nail seen to in casualty? my dad says.

Everything is all right.