How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas (4 page)

Read How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas Online

Authors: Jeff Guinn

Aunt Lodi was gentler than Uncle Silas, but she was concerned about me, too.

“I want you to be happy, Layla,” she said as we carried a basket of clothes down to the river to wash them. “You are intelligent, and warm-hearted, and I understand all your dreams to travel and help the poor. But you must be practical, too. It is hard, even impossible, for a woman to make her way alone in the world. Perhaps you could find a husband who wanted to do the same things.”

“There's no one like that in Niobrara,” I said gloomily. “When any man here looks at me, he sees the farm instead of Layla. And if I can't travel away from here, how can I meet a man who would love me for who I am, rather than what I'm going to inherit?”

“We'll pray about this, you and I,” Aunt Lodi replied. “You are too special for your dreams not to somehow come true.”

A few days later, Aunt Lodi suggested to Uncle Silas that the three of us make the forty-mile trip to Myra.

“We all need new clothes, and I've heard so much about the wonderful tomb there that I'm eager to see it,” she said. Of course, my uncle and I both knew about the tomb to which she referred. For many years, Myra and its surrounding towns had been blessed by the presence of Bishop Nicholas, by all accounts a wonderful man who loved everyone and who encouraged generosity of spirit. It had been during his lifetime that the mysterious gift-giver began leaving his presents, and there had been some rumors that Nicholas was the one doing it. But in 343 he died quietly in the night. The community responded by building a splendid new church in his honor, and his body was placed in an elaborate tomb. Almost immediately, sick people began coming to the tomb to pray for cures, and some of them claimed they had miraculously been healed. And when the gift-giver continued coming quietly by night and leaving food or clothing to those in need, everyone knew it couldn't have been Bishop Nicholas after allâwhich is when the stories really took on new, fantastic tones. Now people whispered that the mysterious person had magical powersâhe could turn himself into the wind, perhaps, and whistle into houses through cracks under doors.

So, a trip to Myra was exciting in several ways. The possibility of new clothes meant little to me. I never really cared what I wore. But I did want to see the wonderful tomb, and any time I could be somewhere different than my old familiar hometown, I was ready to go. Though I had been taken by my uncle and aunt to small communities near Niobrara, I had never traveled so far before, or to such a big city. If going to Myra wasn't quite the adventure of which I'd been dreaming, it was still closer to that dream than anything I'd previously experienced.

It took several days to prepare for the journey. Uncle Silas had to rent a cart, and a mule to pull it. Aunt Lodi and I baked extra loaves of bread and bought some dried fruit in the town market. Going forty miles would take at least two days. We needed food to eat on the way. There were no paved roads between Niobrara and Myra, just well-worn paths where dust swirled a little less because the dirt was so hard-packed by generations of feet, hooves, and wheels.

I loved the trip to Myra, though it also frustrated me. It was wonderful to watch other travelers, many of them wearing exotic-looking robes. We passed caravans of heavily-laden camels and could smell the aroma of the rare spices they were transporting. But the trip took so long! When the wheel of our cart caught in a rut, it took an hour for my uncle, sweating, to wrench it out. I wanted to help, but as a woman I was required to stand quietly to the side, the hood of my robe pulled modestly around my face. How boring!

But there was nothing boring about Myra, which had so many buildings you could actually see them hundreds of yards ahead before you even entered the city! People milled about, and animals added moos and bleats to the general cacophony, and the market in the center of the city must have had a hundred different stalls. Uncle Silas left Aunt Lodi and me at the market, telling us to look around for good bargains on new cloaks while he found a stable for the mule and an inn for us to sleep in that nightâwe would be staying for several days. Aunt Lodi was eager to begin shopping, but I wanted to do something else.

“Please, let's go right away to see the tomb of Bishop Nicholas,” I pleaded. “The cloaks will still be for sale in the morning.”

“The tomb will be there in the morning, too,” Aunt Lodi replied. “Why are you so anxious to see it?”

I didn't know. I just felt I had to go there. It took several minutes, but I convinced my aunt that it would be all right for me to find the tomb by myself while she shopped. Aunt Lodi made me promise that I would take only a brief look at the tomb, then rejoin her at the market.

“You and Silas and I can go take a long look at it tomorrow,” she said. “Be certain you meet me right back here by sunset. I don't want you walking the streets of a strange city all alone after dark.”

I promised I would, and hurried off. It wasn't hard to find the tomb. The first woman I asked knew exactly where it was, though she warned me I might not be able to get a very good look at it.

“The cripples, you know, gather around it before dawn and spend all day praying to be healed,” she said. “Bishop Nicholas, of course, is given credit for granting such miracles, and perhaps he does. My hands get very swollen and sore sometimes; I'm thinking of going to the tomb and praying to him myself.”

And she was right. The tomb was actually inside the church, and a magnificent thing it was, higher all by itself than any structure I had ever seen before, with the date of Bishop Nicholas's death carved into the stoneâDecember 6, 343, it wasâas well as his likeness. He had been, apparently, a striking-looking man, with long hair and a beard. He appeared a bit stouter than most, but then bishops also ate better (and, apparently, more) than the rest of us. I wanted to look closer at the carving of the bishop, but dozens of cripples surrounded the tomb and I didn't want to push them aside. Some were blind, others couldn't walk, and their crutches lay beside them as they prayed, silently or out loud, to be healed. As I stood behind them, I also noticed in the shadows to the side of the tomb a number of other people, all ragged and hungry looking, quietly waiting, though I had no idea for what.

“Who are they?” I asked a reasonably well-dressed man who was standing beside me.

“It's an odd thing,” he said. “Ever since this tomb was built, poor people passing through Myra seem to get comfort from just being near it.”

As I stood as close to the tomb as I could, a strange feeling came over me. It wasn't sadness, though I felt very badly for the crippled and poor people, and wanted with all my heart to do something to help them. And it wasn't exactly excitement, either, though I was thrilled to be in a large city for the first time in my life. If I had to describe it, I would say I felt inspired. My eyes moved from the poor people to the carving of Bishop Nicholas's kind face, back and forth between them while time passed and I didn't notice the afternoon shadows growing long and deep. Finally, as night fell, everyone began to leave. I felt as though I was being jostled awake from a wonderful dream. Then I realized it was nighttime, and I remembered Aunt Lodi waiting back at the market.

She was very angry with me when I finally returned, a bit out of breath because I'd run all the way from the tomb.

“If Silas knew you'd been out gallivanting until after dark, he'd pack up the cart and have us back on the road to Niobrara at dawn. What was there about the bishop's tomb that made you forget your promise to come right back?”

I don't recall my answer, though I do remember she didn't tell Uncle Silas about how I had disobeyed. The three of us stayed in Myra for four days. We bought clothes and ate wonderful food and wandered around the city marveling at its size and all the people who lived there. Twice, we went to see the bishop's tomb. Both times, I was overcome by the same sense of inspiration. I did not tell my uncle and aunt about it, but afterward when we were back home in Niobrara I found myself having the same dream almost every night. I would be in a different place in each dream, but in the company of the same man. He was older than me and somewhat overweight. His hair and beard were white. No one who looked like him lived in Niobrara, yet his face was very familiar.

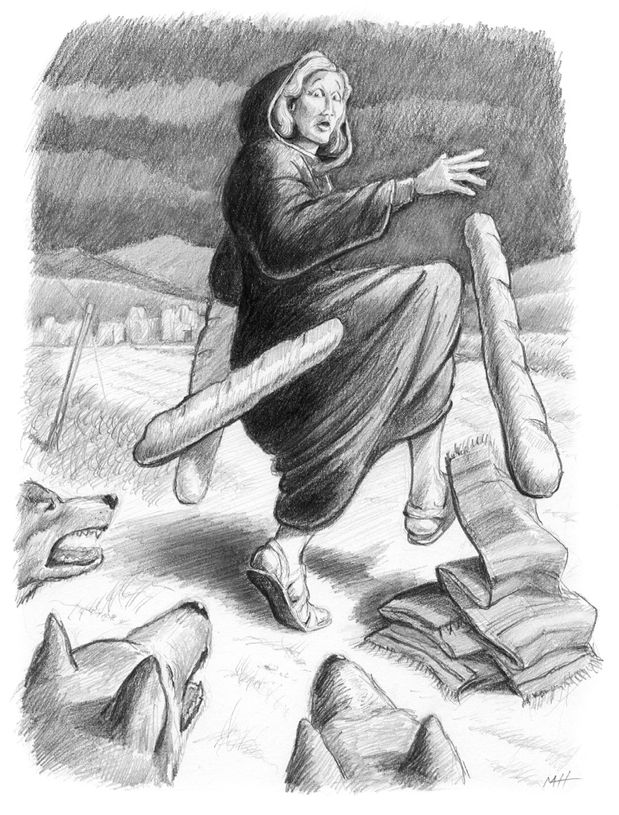

The first dog kept barking, and several more joined in the thunderous chorus. There was nothing for me to do but turn and run. As I did, I dropped the loaves of bread, which were long and thin, and then I lost my grip on the blankets as I dashed madly through the darkness back toward the city.

CHAPTER

Two

Two

Â

Â

Â

Â

I

was twenty-four when first my aunt, and then my uncle, passed away. Though I mourned them, it was hardly a surprise when they died. Aunt Lodi was fifty-seven, and Uncle Silas was fifty-nine. By the standards of the day, each had reached great old age. And, in a way, it was merciful that Uncle Silas quickly followed Aunt Lodi to heaven, because in the days after she was gone he was simply lost without her. The wheat in his fields remained un-harvested. He sat in our hut staring into the fire, saying very little. I did the best I could to comfort him, but it soon became obvious he was not long for life, either.

was twenty-four when first my aunt, and then my uncle, passed away. Though I mourned them, it was hardly a surprise when they died. Aunt Lodi was fifty-seven, and Uncle Silas was fifty-nine. By the standards of the day, each had reached great old age. And, in a way, it was merciful that Uncle Silas quickly followed Aunt Lodi to heaven, because in the days after she was gone he was simply lost without her. The wheat in his fields remained un-harvested. He sat in our hut staring into the fire, saying very little. I did the best I could to comfort him, but it soon became obvious he was not long for life, either.

“Marry, Layla,” he said during our last conversation. His voice was quite weak. “Find a good husband.”

“I promise,” I replied, and felt somehow I was telling the truth, even though I was no more willing than ever to marry a man from Niobrara and become a farmer's wife.

Uncle Silas's death created a very difficult situation for me. As his only heir, his farm became mine. But no woman in Niobrara, or anywhere else that anyone in Niobrara knew of, lived alone and managed a farm by herself. This was supposed to be done on her behalf by a husband or son or uncle or cousin, or at least a close male friend. I had none of these.

“Choose a man and get on with your life,” people told me over and over. When I tried to hire workers to harvest the grain, they all refused to work for a woman. A year after my uncle had passed I was still unmarried, and even the other women in the village began to act uncomfortable around me. Once, several of them pulled me aside and told me I was acting “unnatural.”

Layla

I knew better. I had spent the year making plans. Never forgetting Aunt Lodi's words, I was not only keeping my dreams, I was going to try to make them come true.

Besides the farm, which was worth something itself, Uncle Silas had bequeathed me some money. It wasn't a fortune by any means, but the small pile of coins he'd accumulated over the years amounted to enough for what I neededâa sum sufficient to keep me in simple food and clothing for a long time, with quite a bit left over. And I knew what I wanted to do with the money that was left.

The mysterious gift-giver of local legend might be magical, or might not. I could not be that personâI certainly had no special powersâbut I could do some of the same things. I would take my money and use it to buy blankets and cloaks and food for people in need. During the year between my uncle's death and the time I left Niobrara, I thought long and hard about how best to do this. Gradually, I realized several things.

First, as a giver I, too, must remain anonymous. Even the very poorest people still had pride and might be insulted by a strange woman simply handing them gifts. The legendary gift-giver, whoever that was or might have been, was right to leave presents at night and in secret.

Second, I must distribute my gifts as widely as possible. There were poor, deserving people everywhere. To stay in one place for too long would also cause another problem. After a while, people in the area would begin to stay awake at night in the hope that they could find out who the gift-giver might be. Besides, I wanted badly to travel.

Other books

Barbara Metzger by Cupboard Kisses

Chapel Noir by Carole Nelson Douglas

The Witch's Tongue by James D. Doss

Deliver Me by Faith Gibson

0316246689 (S) by Ann Leckie

Mr. Big: A Billionaire Romance by Gold, Alexis

Love Beyond Expectations by Rebecca Royce

A Box of Matches by Nicholson Baker

B009XDDVN8 EBOK by Lashner, William

Alien Penetration by Morgan, Yvonne