How the West Won: The Neglected Story of the Triumph of Modernity (58 page)

Read How the West Won: The Neglected Story of the Triumph of Modernity Online

Authors: Rodney Stark

Tags: #History, #World, #Civilization & Culture

An equally important aspect of the British nobility was that younger sons “automatically descended into the gentry,” as Beckett pointed out. They could use the “courtesy title ‘lord,’ but only for themselves, not for their children.”

32

For example, Winston Churchill’s father was Lord Randolph Churchill because he was the third son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, but his son Winston could not call himself a lord. Thus did the overwhelming number of noble English offspring “disappear” into the population of commoners. Nor could younger sons expect to live off the family lands (as was typical on the Continent). Rather, as Beckett noted, many younger sons received a “cash payment to set themselves up as best they could.”

33

In each generation, then, a large number of younger sons of the nobility were forced to find gainful occupations and professions. They not only staffed the church and the officer corps but also were active in law, academia, banking, mining, manufacturing, and other forms of commerce. The flood of well- educated and well- connected young men into these occupations brought with them substantial prestige and power.

The Expansion of British Education

The rise of the bourgeoisie was accompanied by what Lawrence Stone called an “educational revolution in England.”

34

As noted in chapter 15, massive educational changes began in the mid-sixteenth century. First was the establishment of thousands of “petty schools” for the purpose of teaching “basic literacy to the bulk of the population.”

35

Nothing like this had ever been attempted before, anywhere. These efforts were financed not by the government but by a huge number of private bequests for the establishment of local schools to provide free instruction. By about 1640 England had a petty school for every 4,400 people, or “one approximately every twelve miles.”

36

Also

free were schools that taught not only reading but also grammar, writing, arithmetic, and bookkeeping. And, of course, there were the sophisticated “grammar schools,” meant to prepare students for entry into the universities and the Inns of Court (law school). Perhaps surprisingly, the grammar schools were not limited to the children of the aristocracy. For example, from 1636 to 1639 Norwich grammar school sent on to the University of Cambridge the sons of “one esquire, four gentlemen, two clergymen, a doctor, a merchant, an attorney, a weaver, a carpenter, a fishmonger, two staymakers and two drapers.”

37

As that list attests, in this era many from humble origins went to the great universities of Oxford and Cambridge. In fact, at no time between 1560 and 1629 were the majority of university students classified as “gentlemen.”

38

This era saw a dramatic expansion in the enrollment of sons of the bourgeoisie. For example, the sons of merchants and tradesmen accounted for 6 percent of the students at Caius College, Cambridge, in 1580–90; by 1620–29 the figure had increased to 23 percent. Similarly, enrollment by the sons of clergy and the professions grew from 5 percent to 19 percent. Hence, by 1620–29, nearly half (42 percent) of the students were from the bourgeoisie.

39

By 1630, well before the takeoff of the Industrial Revolution, Britain had by far the best-educated population in the world. Furthermore, large numbers of those involved in industry and commerce had attended the elite universities, forming a critical mass of educated leaders to launch the Industrial Revolution. A remarkable study by the historian François Crouzet, based on 226 founders of large industrial firms in Britain from 1750 to 1850, revealed that 9 percent were the sons of aristocrats and 60 percent were the sons of the bourgeoisie. A similar study by the sociologist Reinhard Bendix, based on 132 leading industrialists from 1750 to 1850, reported that two-thirds were from families already well established in business.

40

The American “Miracle”

When the Industrial Revolution began in Britain in about 1750, North America had hardly any manufacturing, aside from a large shipbuilding industry based on plentiful local supplies of timber and other materials (in 1773 American shipyards built 638 oceangoing vessels).

41

Ships aside,

manufacturing in America was limited to small workshops making items such as shoes, horse harnesses, nails, pails, and simple hand tools for the local market. Only the many little gunsmith shops, dedicated to fabricating the newly invented rifle, could compete with British goods in terms of quality. Nearly everything else in the way of manufactured goods was imported from England.

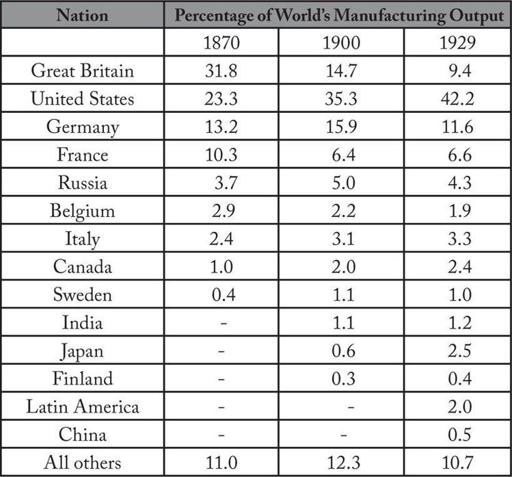

A century later the United States was catching up with Britain as a manufacturing power, and in fact the Americans soon surpassed the British and everyone else, as can be seen in table 17–1. In 1870 Great Britain produced about a third (31.8 percent) of all the world’s manufactured goods and the United States produced about a quarter (23.3 percent). By 1900 the United States was producing more than a third (35.3 percent) of all the world’s manufacturing output, compared with 14.7 percent produced by Great Britain and 15.9 percent by Germany. By 1929 the United States dwarfed the world as a manufacturing power, producing 42.2 percent of all goods, compared with Germany’s 11.6 percent and Britain’s 9.4.

This “miracle” of production was possible only because America had also forged ahead in the Industrial Revolution. Indeed, during the nineteenth century it seemed as if all the inventors lived in the United States.

42

Why had this occurred? For all the same reasons that the Industrial Revolution had originated in Britain—political freedom, secure property rights, high wages, cheap energy, and a highly educated population—plus a plenitude of resources and raw materials and a huge, rapidly growing domestic market. In fact, by early in the nineteenth century, the United States surpassed Britain in all these crucial factors.

Property and Patents

The early American colonies came under English common law. Therefore individuals had an unlimited right to property that they had legally obtained, and not even the state could abridge that right without adequate compensation. Eventually that became the basis of American property law as well. Thus, the state could not seize iron foundries as had taken place in China, although it could purchase them should that seem desirable—as the socialist government of Britain did when it nationalized most basic industries right after World War II (until government control of these industries proved so unprofitable that they were transformed back into private companies).

Table 17–1: Percentage Shares of the World’s Manufacturing Output

Source: League of Nations, 1945

But this approach to property law was inadequate for protecting inventions and other forms of intellectual property. Consider the steam engine. Obviously, James Watt owned the steam engine he had constructed—it was his personal property and to steal it would have been a crime. But what if someone made an exact copy? Was it that person’s? If so, then how could Watt or any other inventor benefit from inventing? The solution was to grant a

patent

on inventions. Watt, for example, secured the exclusive right to ownership of all steam engines based on his principles for a number of years, including the right to sell, rent, license, or otherwise exploit that invention. The British Crown had initially granted patents, but the government formalized the process during the reign of Queen Anne (1702–1714), requiring applicants to submit a full description of their invention.

The American Founders regarded patent rights as so important that they wrote them into the Constitution: Article I, Section 8, states: “The Congress shall have power … to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” In keeping with this mandate, in 1790 Congress passed the U.S. Patent Act, which gave inventors an exclusive right to their inventions for a period of fourteen years. This was later amended to twenty-one years. Initially few applied for patents—only fifty-five were issued between 1790 and 1793. But by 1836 ten thousand patents had been registered. Then came an inventive explosion, and by 1911 one million patents had been granted. Among them were patents covering the invention of electric lightbulbs, movies, sound recordings, telephones, and the zipper.

Although it has often been overlooked, American laws concerning bankruptcy also facilitated industrial development. In Britain and most of Europe, laws concerning debts were brutal: in Britain those unable to pay their debts were sentenced to debtors’ prison, from where “they could scarcely repay their obligations let alone start new careers,” the historian Maury Klein noted. But America had no debtors’ prisons, and the law limited legal liabilities sufficiently “to give debtors enough breathing space to survive their downfall and get back into the game.”

43

Many famous American industrialists and inventors survived early failures. More than that, entrepreneurs dared to take risks.

High Wages

If wages were high in Britain, they were towering in America. American wages were so high because employers had to compete with the exceptional opportunities of self-employment in order to attract adequate numbers of qualified workers. Alexander Hamilton explained shortly after the American Revolution, “The facility with which the less independent condition of an artisan can be exchanged for the more independent condition of a farmer … conspire[s] to produce, and, for a length of time, must continue to occasion, a scarcity of hands for manufacturing occupation, and dearness of labour generally.”

44

Good farmland was so abundant and so cheap that even those who arrived in America without any funds could, in several years, save enough to buy and stock a good farm. Consider that in the 1820s the federal government sold good land for $1.25 an acre while wages for skilled labor amounted to between $1.25 and $2

a day.

45

Consider, too, that in America there were no mandatory church tithes, and taxes were low.

Given higher labor costs, how could American manufacturers possibly compete on price? Through better technology. American industrialists eagerly embraced promising new technology if they anticipated a sufficient increase in worker productivity. For if workers equipped with a new technology could produce a sufficient amount more than could less mechanized workers in Europe, this reduced the relative cost of American labor

per item

. Technology made it irrelevant that American workers were paid, say, three times as much per hour as European workers (as they often were), when they produced five or six times as much per hour. That increased productivity offset both their own higher wages and the capital investments their employers made in new technology. Throughout the nineteenth century Americans led the way in developing and adopting new techniques and technologies. And they did so without provoking the reactionary labor opposition to innovation that nineteenth-century British capitalists so often faced—no Luddites smashed machines in the United States. Why not? Because, given the constant shortage of labor, American manufacturers competed with one another for workers and used a significant portion of their productivity gains to increase wages and to offer more attractive conditions.

Worker productivity was the basis for the incredible growth of American manufacturing shown in table 17–1, and why it came largely at the expense of the British. Americans were not more humane employers. They were more sophisticated capitalists who recognized that satisfied, productive workers are the greatest asset of all. This attitude toward labor brought many skilled and motivated British and European workers to America, and the expanded labor force sustained ever more industrial growth. Too many published discussions of the rise of American industry (especially in textbooks) denounce the “robber barons” and “plutocrats” for supposedly exploiting labor, and especially for abusing immigrants. Such tracts are anachronistic, comparing labor practices back then with those of today, almost as if factory latrines in 1850 should have had flush toilets. The proper comparison is between the situation of American labor and labor in the other industrializing nations in the same era.

In addition to being highly paid and equipped with the latest technology, American workers were notable in another way. They were far better educated than workers anywhere else in the world (excluding Canada).

Educating a Nation

During his 1818 visit to America, the English intellectual William Cobbett wrote home: “There are very few really

ignorant

men in America.… They have all been

readers

from their youth up” (his italics).

46

From the earliest days of settlement the American colonists invested heavily in “human capital,” as modern economists would put it. And in this, religion played a primary role.