How They Started (34 page)

Authors: David Lester

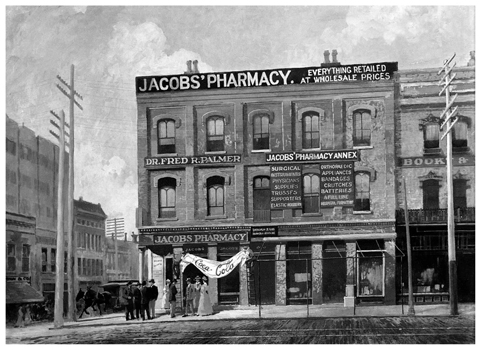

Coca-Cola was first sold as “medicine” for 5 cents a glass in pharmacies.

In the first year, John sold just nine glasses of Coca-Cola a day, making around $50 in total ($1,170 today). It had cost John $70 to create and advertise the drink, so he incurred a loss. But he persevered. Encouraged by the drink’s popularity with customers, John remained convinced he would eventually make something of it.

First named Pemberton’s French Wine of Cola, the alcohol in the drink was quickly replaced by sugar to make it more appealing to drink. The drink was renamed Coca-Cola by John’s bookkeeper, Frank Robinson, who also wrote the name for the logo in the distinctive script that is still in use today. The name is derived from two key ingredients: leaves from the coca plant and the caffeine-rich kola nut. Until 1905, the drink even contained traces of cocaine, added for its medicinal effects.

John’s young company started to grow sales of its drink by getting other pharmacies to sell Coca-Cola too. It sold 25 gallons of syrup to drugstores and made sure that all the stores that sold the drink had hand-painted Coca-Cola signs to help promote it. John persuaded six local businessmen to invest in the company to help him finance this expansion.

Coca-Cola’s famous advertising campaigns have roots in its early history: soon after the drink was created, John placed the first newspaper ad in the

Atlanta Journal

, inviting people to try “the new and popular soda fountain drink.”

Sadly, John died in 1888 and never saw his drink concoction taken to the masses. The person to do this was Atlanta businessman Asa Griggs Candler, who bought the rights to the drink for $2,300 ($54,400 today). It took Asa three years to secure rights to the business, as a very ill John had also sold rights to another businessman and given exclusive rights to his son, which took some time to unravel.

Asa had a vision for the product: to turn the now-popular drink from a beverage into a business. He disbanded the pharmaceutical arm of the company and partnered with his brother, John Candler, and John Pemberton’s bookkeeper, Frank Robinson. Together they raised $100,000 ($2,370,000 today)—then a very substantial sum—to kick-start the business.

In 1891, Asa had full control of the business, and within a year he had increased sales of Coca-Cola syrup tenfold. In 1893, the company was incorporated and The Coca-Cola Company was officially born.

The company soon began a huge marketing campaign, using new advertising techniques. To spread the word, Asa gave away coupons for free Coca-Cola samples in newspapers, and offered pharmacists two gallons of the syrup if they agreed to give away one gallon’s worth when people produced his coupon. He supplied the pharmacists with urns, clocks, calendars, and scales all bearing the brand name. The combination of strong branding and a drink that appealed to so many people worked wonders, and sales grew fast.

Just four years later, in 1895, Asa had grown demand for his product so much that he needed to build syrup plants in Chicago, Dallas and Los Angeles. He declared to his shareholders that “Coca-Cola is now drunk in every state and territory in the United States.” Given the far reach of today’s mass media, it might be easy to miss just what a major achievement in advertising this really was. This, after all, was an era in which it took days to travel across the country. Likewise, there was no radio or television, and so to achieve product placement in every state so quickly was quite phenomenal.

The combination of strong branding and a drink that appealed to so many people worked wonders, and sales grew fast.

Until 1894, Coca-Cola was sold only by the glassful. But then a Mississippi businessman named Joseph Biedenharn had the idea to bottle Coca-Cola at his factory. He sent a dozen bottles to Asa; Asa hated the product and quickly dismissed it. He overlooked this crucial development again in 1899 when two lawyers from Chattanooga, Tennessee, Benjamin F. Thomas and Joseph B. Whitehead, secured exclusive rights from Asa to bottle and sell the beverage in nearly all of the states, for only $1. In fact, Asa was so sure that this idea would amount to nothing that he didn’t even bother collecting the dollar!

This was the start of Coca-Cola’s unusual corporate structure, which continues to this day. The Coca-Cola Company supplies syrup, called concentrate, to customers all over the world. Some of these customers are restaurants and bars, which sell the drink by the glass, much like the original pharmacy customers. The other group of customers are bottling companies, which add carbonated water to the syrup in a factory and bottle it for sale in shops.

Thomas and Whitehead began by opening bottling plants in Chattanooga and Atlanta, but soon realized there was a far better way for them to distribute bottled Coca-Cola across the country. The two Chattanooga lawyers were joined by John Thomas Lupton and the trio split the US into three territories, selling bottling rights to local entrepreneurs. Not only did this reduce the amount of capital the lawyers needed, as local entrepreneurs used their own money, but it also provided local knowledge and the commitment of business owners, which would have been very hard to set up any other way. The first sub-licensed bottler began in 1900, and by 1909 there were 400 Coca-Cola bottling plants across America.

By the turn of the century, Asa had increased Coca-Cola’s sales to 40 times its 1890 level, and his continuing advertising campaign and his free samples had spread the name “Coca-Cola” across the country.

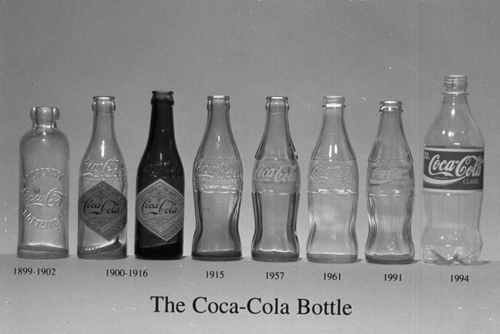

Coca-Cola’s bottle progression over nearly a century.

The drink was first taken overseas by Asa’s son, Charles, on a trip to London. Charles took a jug of syrup with him and gathered modest orders for five gallons. Coca-Cola was first sold in England on August 31, 1900, and gradually it built enough momentum to be sold in London’s prestigious Selfridges department store and the London Coliseum.

After seeing the success of the bottled drinks, The Coca-Cola Company decided to license out bottling rights to overseas territories itself. The first international bottling plants began in Canada, Cuba and Panama in 1906; plants in the Philippines and Guam followed shortly afterward in 1912. As he had done so effectively in America, Asa supported the new supplies of drinks with a thorough marketing campaign, to ensure that Coca-Cola’s bright-red logo was seen in stores and cafés everywhere.

Of the companies granted rights to bottle Coca-Cola around the world, most were brewers. This worked well, as the brewers already had bottling plants and expertise, so it was relatively easy and quick for them to add the new drink to their range. The brewers also already had distribution networks through their existing customer base, which meant that Coca-Cola had access to stores, bars and restaurants far faster than it would have done had it set up a brand-new business from scratch in a new country.

As he had done so effectively in America, Asa supported the new supplies of drinks with a thorough marketing campaign, to ensure that Coca-Cola’s bright red logo was seen in stores and cafés everywhere.

The drink had become very well known, and it was clearly successful, so inevitably a number of competitors appeared—though, of course, none knew the precise recipe for the drink, which was kept secret. The Coca-Cola Company grew concerned that it was too easy for customers to be given a different drink and mistakenly think it was “The Real Thing”—which meant not only that Coca-Cola would lose out on the sale but, if customers didn’t enjoy the rival drink, that it would lose out on future sales, too. Something had to be done. So the company decided to come up with a distinctive bottle to ensure its product stood out. In 1915, following a design contest, the now-famous bottle was introduced. Created by the Root Glass Company of Terre Haute, Indiana, the winning design was chosen for its attractive and original appearance and because, even in the dark, people could easily identify it.

After nearly three decades of turning the drink into a substantial and successful business, Asa eventually sold the business in 1919 to Ernest Woodruff for $25 million (worth roughly $315 million in today’s money); his son Robert Woodruff became president in 1923. The company was reincorporated as a Delaware corporation and listed on the New York Stock Exchange, selling 500,000 shares to the general public at $40 per share. Coca-Cola was now firmly established as an American icon, but Woodruff’s mission was to go global. His vision was to create a brand that was “in arm’s reach of desire.”

During the 1920s and 1930s, Woodruff set his sights on international expansion. When he took over in 1923, Coca-Cola was strongly established in North America, had some bottling arrangements in South America, and had just opened its first European bottling plant in France. From this base, Woodruff’s Coca-Cola went on to open additional plants in Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Belgium and Italy in the 1920s. In 1926, Coca-Cola set up a Foreign Department, which became the Coca-Cola Export Corporation in 1930. In all the countries Coca-Cola expanded into, a creative, vibrant and culturally relevant advertising campaign followed.

A significant international move occurred in 1928, when Woodruff began a partnership with the Olympic Games in Amsterdam. A thousand bottles of Coca-Cola accompanied the US team, and the drink was on sale in the Olympic stadium. Vendors wore caps and coats emblazoned with the Coca-Cola logo, and the drink was also sold at surrounding cafés, restaurants and stores.

Elsewhere, Woodruff affixed the company logo on everything from Canadian racing dog sleds to bullfighting arenas in Spain. By the start of World War II, Coca-Cola was in 44 countries. A marketing genius, Woodruff continued to develop the company’s successful, but limited, line. He introduced the six-pack (making the drinks more transportable and encouraging people to buy in bulk) and the open-top cooler. Coca-Cola was available in vending machines from 1929 and was advertised on the radio from 1930. In 1935, bottlers hired women to act as door-to-door salespeople for the drink, with a target of 125 calls per day.

In all the countries Coca-Cola expanded into, a creative, vibrant and culturally relevant advertising campaign followed.

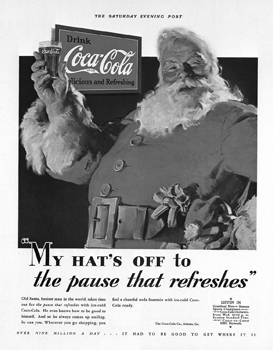

In a marketing scheme that was to have repercussions for little children everywhere, Coca-Cola’s famous red-suited Santa Claus made his debut at Christmas 1931, banishing the long-established and previously unchallenged green Santa into the mists of time.

Santa Claus dressed in red is now a globally recognized figure.

Throughout World War II, Coca-Cola continued to manufacture, offering the drink for 5 cents to any serviceman, whatever country he was in, regardless of the cost to the company. Bottling plants were opened to supply troops with the drink, following a request from General Eisenhower himself on June 29, 1943. Eisenhower asked for the shipment of materials for 10 bottling plants to be sent to North Africa along with three million bottles of Coca-Cola and enough supplies to make the same amount twice a month. Coca-Cola responded within six months, setting up a bottling plant in Algiers.