How to Get Away With Murder in America (7 page)

Read How to Get Away With Murder in America Online

Authors: Evan Wright

Tags: #General, #Criminology, #Social Science, #Law

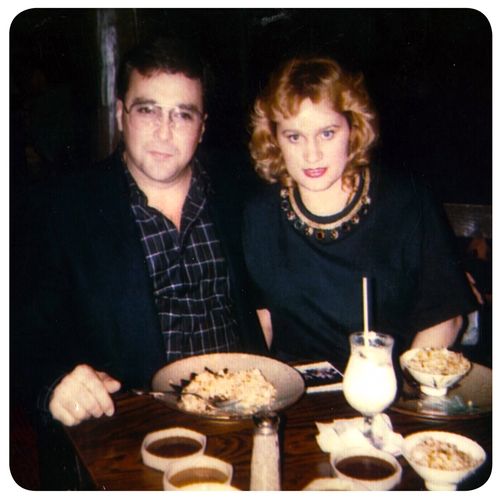

“The Maniac” and his “Legs on the Street”: Albert San Pedro and his third wife, Lourdes, enjoying a nother night on the town, circa 1990.

Courtesy of Lourdes Valdez

“It was like playing cops and robbers”: Detective Mike Fisten, in blue, with a MDPD decoy squad in 1980, before the pursuit of Prado and San Pedro began to consume his life.

Courtesy of Mike Fisten

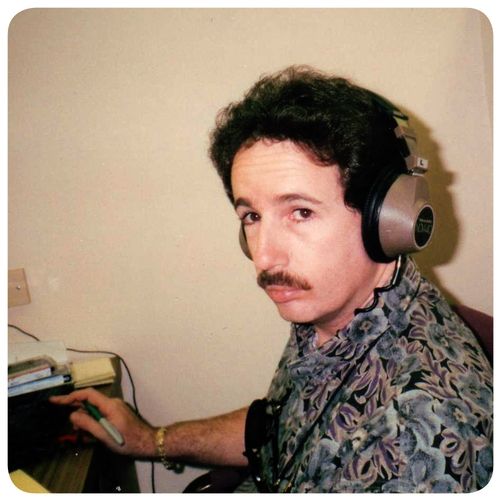

The “last true crime fighter”: Fisten listening to surveillance tapes while on the OCS, circa 1991.

Courtesy of Mike Fisten

Hinman’s primary hope in nailing Erra resided in a coke-addicted Miami attorney named Mark Baer, who had recently been arrested for embezzling money from a client. Hinman had learned that one of Baer’s longtime clients was Bobby Erra. Out on bail and facing financial ruin, Baer was living in a Miami Beach apartment, near his eighty-five-year-old mother. When Hinman sent detectives to offer Baer a deal on his embezzlement charges if he would cooperate against Erra, Baer told them to get lost.

But Fisten saw an interesting detail in surveillance reports on Baer: He had started attending synagogue. “I decided,” says Fisten, “hey, we’re both Jews, both about the same age. He’s never met me, so he doesn’t know I’m a cop. I’ll go to his temple and see what happens.”

Higher-ups balked at authorizing an undercover operation in a place of worship, so Fisten went on his own time. “Mark and I really clicked,” he says. “A couple weeks after we met, we go out to coffee one morning, and Mark told me he had anxiety. I said, ‘Buddy, I understand how stressed you must be, because I’m a cop, and we’ve been investigating you, and we’re going to put your ass in prison for the rest of your life unless you help us get Bobby Erra.’ ”

Thrown by Fisten’s revelation, Baer fell to the floor of the Denny’s where they had met and began flopping uncontrollably. “Fortunately,” Fisten says, “it was just a grand mal seizure.” Fisten accompanied Baer in the ambulance to the hospital, and Baer agreed to enter witness protection and cooperate. Days later, Baer’s mother was hospitalized after Erra and another man allegedly entered her apartment and beat her with her walker. But Baer had already begun spilling his secrets. By his account, he had been an all-purpose attorney, representing Erra in drug deals, carrying bags of cash for him to launder in Bahamian banks, and even unloading coke from smugglers’ planes. Most important, Baer explained that Erra had run his operations with Albert San Pedro and his bodyguard Carlos Redondo until Albert’s arrest in 1986.

Having learned of the connection between Albert and Bobby Erra, Hinman notified federal prosecutors that Operation RHABDO was now targeting Albert and Redondo. The prosecutors approved, unaware of the immunity deal their boss had granted Albert.

To minimize leaks, the OCS investigators rented an apartment in West Miami to use as an undercover office. They moved a truckload of evidence from the 1985 investigation of Albert into the apartment, filling a bedroom. As they opened the boxes, they were stunned to find that no one had ever listened to hundreds of hours of audiotapes. The U.S. military lent the OCS linguists to help transcribe recordings that were in Spanish. As the investigators logged the tapes, they were astonished: Not only did the tapes implicate Albert and Erra in a vast drug-trafficking and money-laundering operation, but they also appeared to implicate Albert in at least two murders. Says Fisten, “The fact that 1,100 hours of this tape had sat unlistened to in a storage room for nearly five years was the biggest debacle of justice I had ever seen.”

During the six-month period during which the tapes were recorded, Albert and Erra’s operation appeared to have taken in about $70 million from drug trafficking and some $3 million from illegal gambling. They apparently laundered at least $9 million in Bahamian banks. The tapes also revealed a separate laundering scheme that involved a corrupt lottery official in Puerto Rico who sold Albert and Erra unclaimed winning tickets in exchange for drug cash. (Notably, Marsha Ludwig would admit to federal prosecutors that around the time she sent her note requesting a pardon for Albert to Governor Graham, she cashed in a winning Puerto Rican lottery ticket for a quarter of a million dollars, though she insisted it was not a payoff but a legitimately purchased ticket.)

To help guide his squad through Albert’s world, Hinman recruited Detective McGruff, from the 1985 investigation case. “I went to work with those guys under protest,” McGruff says. “I wanted nothing to do with San Pedro.” One of the first questions OCS investigators asked McGruff was how his squad had managed to disregard so much evidence in the state case. He answered, “You don’t know what you’re dealing with. You’ll see.”

And soon they did.

A few days before Christmas 1990, the federal prosecutors supervising Operation RHABDO called Hinman into their office and informed him of Albert’s immunity. All Hinman could say was, “You guys have got to be kidding me.” Apparently, Hinman now notes, “Lehtinen kept the deal in his desk.”

Confronted with Albert’s immunity deal several months into their investigation, the OCS sought evidence that Albert was engaging in new criminal activities that his agreement would not cover. Fisten was assigned to surveil Albert with the OCS member to whom he’d grown closest, a detective named Mel Velez. A former Marine and Vietnam vet, Velez shared Fisten’s absolute commitment—bordering on self-righteousness—to police work.

Fisten characterizes their surveillance efforts as worthy of the Keystone Kops. When he and Velez moved onto a boat in a canal near the barbershop they suspected Albert used as a cocaine distribution hub, they awoke one morning to find someone had cut the mooring lines and set them adrift. When they set up an observation post at the water plant by Albert’s house, Hialeah cops tried to arrest them, even after Fisten presented his badge and his business card. Fisten discovered that his home phone had been bugged by a Southern Bell employee, who later pleaded guilty to illegal wiretapping. “Our investigation was like a streetfight,” Fisten says. “And Albert was kicking the shit out of us.”

Federal prosecutors, outraged by the immunity deal their boss had granted Albert, sought to break it. Albert’s immunity did not protect him from state murder charges, and though it lacked crucial language requiring him to cooperate, prosecutors believed it could be voided if Albert perjured himself. They planned to put him under oath before a grand jury and question him about alleged murders he seemed to refer to on tapes the OCS had transcribed. If Albert testified truthfully, he would open himself to murder charges. If he lied, they believed, his perjury would break his immunity and subject him to federal RICO charges. A federal judge would need to rule on whether their strategy was legal, but it was their only hope.

In January 1991, Albert was subpoenaed to testify before a grand jury. Assistant U.S. attorney Diane Fernandez led the questioning, and being grilled by a strong Cuban American woman seemed to rattle Albert. He spoke more than he should have, giving prosecutors just enough, they believed, to prove perjury and nullify his immunity. They charged Albert, along with Erra and Redondo, on several RICO counts, based on evidence provided mostly by Baer and tapes from the earlier state case.

On April 2, 1991, the OCS, accompanied by a SWAT team and two dozen black-clad federal agents, surrounded Albert’s home. Albert’s mother let them in through the kitchen. Albert, dressed in a designer tracksuit, appeared behind her and asked, “What’s this about?”

“You’re under arrest,” Fisten said.

“You can’t arrest me,” Albert said.

“We just did,” several OCS investigators shouted as they cuffed him.

Searching the house, Fisten was struck by the bizarre layout. “He built room after room with no rhyme or reason. Some had no windows. The doors were in the wrong places. It was like being inside a Lego house.” At the house’s Santeria shrine, Fisten made an unsettling discovery. His business card, taken by the Hialeah cops who had tried to arrest him at the water plant, was pinned by a knife to what Fisten called in his report “a voodoo-type figurine.” “I’m no expert on Santeria,” Fisten says. “But clearly he wasn’t wishing me Happy Hanukkah.”

Dexter Lehtinen, who was then in the national spotlight as he prepared to lead the United States’ prosecution of Panamanian dictator General Manuel Noriega, had approved of his prosecutors’ efforts to overturn Albert’s deal. He had little choice: Had he hindered them from pursuing the case, it might have appeared that he was trying to protect Albert. But by allowing them to proceed, his heretofore secret deal with Albert would undergo intense public scrutiny. Whatever deficiencies Lehtinen might have had as a U.S. attorney, though, his political instincts were unerring. After Albert’s arrest, he called a press conference in which he hailed the arrest as a “decisive step against the vicious cycle” of drugs and violence. As he spoke, the Justice Department had already opened a conflict-of-interest probe into his handling of Albert’s deal.

Albert assembled a defense team that would soon include celebrity attorney Robert Shapiro. Erra hired Roy Black, who was also defending William Kennedy Smith against rape charges. For members of the OCS, already a year into the investigation, their battles were just beginning.

One factor that made the case against Erra strong was Mark Baer’s testimony. OCS investigators combed through Albert’s past to find a similar insider to his operations, someone they could turn against him. Baer provided a clue. He said that Albert sometimes sent a bodyguard called “Alex” to negotiate drug deals. Baer described Alex as a Cuban about Albert’s age, physically fit, and possibly a former fireman.

Baer recalled a specific meeting he had attended in 1983 with Alex, Erra, and a drug runner named Hector “Puma” Valdez in order to plan shipments of cocaine to California. OCS detectives tracked down Valdez in prison. He recalled the meeting with Baer, Erra, and another man, but didn’t remember his name, only that “the third man was very quiet and muscular.”

Soon Alex popped up in another branch of the OCS probe. Investigators learned that in 1975, Albert had invested in a

bolita—

an illegal numbers game—founded by a group of Bay of Pigs vets working as valets at the Dream Bar and the nearby Fontainebleau Hotel. Shortly after they started the

bolita,

a run of lucky numbers among ticket holders in Hialeah bankrupted it. Albert sent thugs to get his investment back.

Investigators tracked down three of the failed

bolita

entrepreneurs, and each told matching stories: Albert sent an enforcer named “Alex Padron” and another big guy to collect his money. One of the

bolita

founders, Hector Serrano, said he was at home when the two showed up. The OCS report recounts the occasion:

The two bodyguards produced pistols and announced they were there to take Serrano’s furniture and green 1970 Ford Maverick. Serrano conceded to the Ford but told them they would have to kill him for the furniture. They took the car and left.

Ciro Orizondo, another

bolita

man, told investigators he had shared an apartment at the Fontainebleau with Manuel Revuelta, who was also a partner in the venture. Orizondo had just returned from the pool when Alex and the other bodyguard burst in with guns drawn. The OCS report continues:

Orizondo noticed that Alex had Revuelta on the bed, holding a gun to his head. Alex told Revuelta that if they didn’t pay the money he would blow Revuelta’s brains out.

Orizondo advised Alex that if he shot Revuelta, he would go to the police and put Alex in the electric chair. Alex became irate and, using some type of karate move, kicked Orizondo in the face which caused him to break teeth.

Revuelta offered more details when investigators interviewed him in prison, where he was serving time for drug trafficking. Following the

bolita

failure, Revuelta had gone on to make a fortune smuggling drugs and live like a doper king, with mansions, racing cars, and the requisite puma. But when investigators spoke with him, he still bore a grudge about the shakedown at the Fontainebleau. Alex, he explained, had taken the keys to his prized 1973 Pontiac Grand Prix and stolen it. Revuelta also said that Alex was a fireman; he identified the other bodyguard as El Oso.

Fisten, who had earlier developed a surprisingly friendly rapport with El Oso while putting him away for murder, had never known that El Oso had worked for Albert. When he met with El Oso in prison and asked him about his old boss, El Oso launched into a tirade. Albert was the worst boss he’d ever had. Too cheap to buy a remote starter, he made El Oso start his car every day to check for bombs. He once ordered him to beat a man because he’d dated a girl Albert had a crush on in high school. El Oso had finally quit after Albert ordered him to kill a pathetic old Cuban dope smuggler over a ten-thousand-dollar debt. He told Fisten, “I can’t kill a man for ten G’s.”

When Fisten brought up Alex, El Oso told him that was an alias for his best friend, Ricky Prado. “They were friends,” Fisten says, “so whenever he brought him up, I acted like I wasn’t interested. The more he talked about Albert, the more he gave up Alex.” Fisten adds, “I almost felt bad for El Oso. He hadn’t intended to hand us Ricky, but he did.”

El Oso detailed many an adventure with Ricky when they had donned their Transworld detective badges and taken care of business for Albert. He confirmed the

bolita

story, bragged about how clever Ricky was at making bombs, hinted at his role in murders, and described numerous arsons they had set, including some that targeted Albert’s family members. According to El Oso, they had torched Albert’s aunt’s house because of a business dispute, and burned Albert’s cousin’s car after he declined to work for Albert as an accountant.

While El Oso gabbed about Ricky, Detective McGruff tracked down the title to the 1973 Grand Prix that Manuel Revuelta claimed he’d stolen from him. The title showed that ownership of the car had been transferred to Ricky and Maria Prado by means of an unusual power-of-attorney document on which Revuelta’s signature appeared to have been forged. When McGruff questioned the notary public who’d certified it, she admitted that she had done so fraudulently.

The forged transfer document was a smoking gun. It corroborated witness statements and linked Ricky to numerous predicate acts. One of the peculiarities of RICO law is that normal statutes of limitation—five or seven years for most crimes—don’t apply. Offenses Ricky committed in the 1970s could still be prosecuted fifteen years later. Says Fisten, “The moment [McGruff] came back with that forged title, Ricky’s ass was cooked. The problem was we didn’t know where to find him.”