How to Grow Up

Authors: Michelle Tea

A

PLUME

BOOK

HOW TO GROW UP

P

HOTO BY

L

YDIA

D

ANILLER

MICHELLE

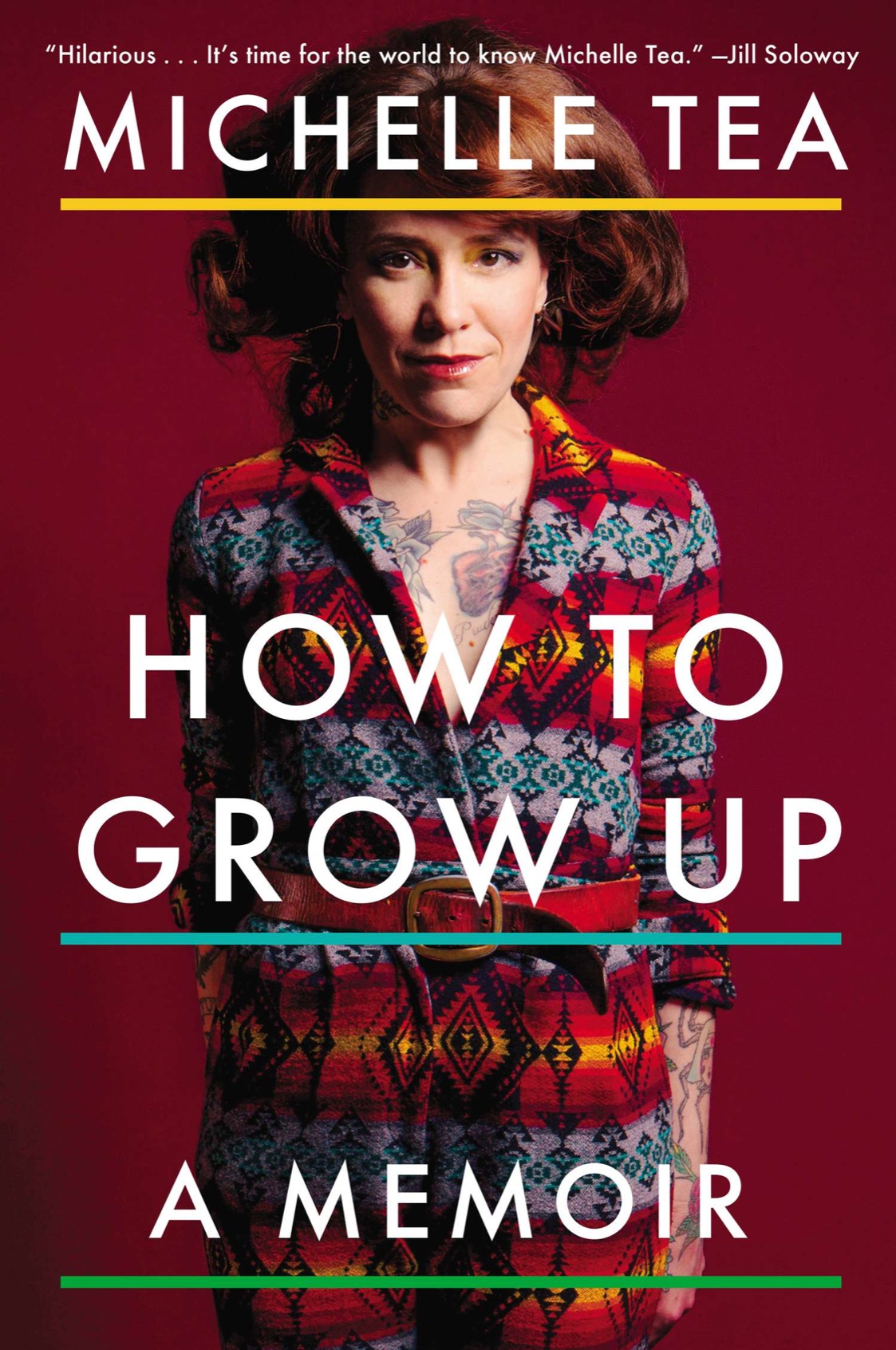

TEA is the author of four memoirs, one novel, a collection of poetry, and a young adult fantasy series. She is the creator and editor of Muthamagazine.com, and she blogs regularly about her attempts to get pregnant at Getting Pregnant with Michelle Tea on xoJane.com. She is founder and artistic director of RADAR Productions, a literary organization that produces monthly reading series, the international Sister Spit performance tour, the Sister Spit Books imprint on City Lights, and other events.

Praise for

How to Grow Up

“Full of insights and weirdness, crazy hope and transcendent humor and despair,

How to Grow Up

is a riveting read for anyone who's clawed their way into adulthood kicking and screaming, or knows someone who's still clawing. I can't recommend it enough.”

âJerry Stahl, author of

Happy Mutant Baby Pills

“If this is your first introduction to the force of nature known as Michelle Tea, get ready for a new hero in your world. Her ferociously wild life has served up some of the juiciest stories in memoir and now she reflects on that life with her singular humor and brazen honesty at full tilt. Few writers come off so scrappy and so elegant at the same time.”

âBeth Lisick, author of

Yokohama Threeway

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Plume, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2015

Copyright © 2015 by Michelle Tea

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

REGISTERED TRADEMARKâMARCA REGISTRADA

REGISTERED TRADEMARKâMARCA REGISTRADA

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Tea, Michelle.

How to grow up : a memoir / Michelle Tea.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-698-15081-2

1. Tea, Michelle. 2. Authors, Americanâ20th centuryâBiography. I. Title.

PS3570.E15Z46 2015

813'.6âdc23

[B] 2014032902

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the author's alone.

Cover design: Jaya Miceli

Cover photograph: Lydia Daniller

Version_1

Â

3. My $1,100 Birthday Apartment

4. I Have a Trust Fund from Godâand So Do You!

5. Beware of Sex and Other Rules for Love

9. Getting Pregnant with Michelle Tea

10. Ask Not for Whom the Wedding Bell Tolls

12. WWYMD: What Would Young Michelle Do?

Â

P

erhaps some of you have glided into adulthood with all the grace of a swan, skimming lightly into an adult living situation, adult relationships, adult jobs and income, and, most important, an adult sense of confidence, of a solid place in the world, of stability.

Who

are

you people? I'm not sure you actually exist.

If you are not yet an adult and fear you may never be one; if you suspect you in fact

may

be an adult, but your grasp on both the concept and the lifestyle is shaky enough to wake you up at night; if you spend too much time longing for items you can't quite afford and break into a cold sweat whenever you do part with some of your hard-earned cash; if your sliding-scale therapist has diagnosed you with post-traumatic stress disorder from the dysfunctional formative years you're clambering out of; if you are slowly learning how to clean your house; if you are slowwwwwwwwly learning how not to date narcissists; if you've spent

too much time with too much booze in your belly; if you never went to college; if you have embarrassing spiritual inclinations that lead you to whisper affirmations under your breath and hiss occasional desperate prayers to unknown unicorn goddesses; if you have a stack of unread self-help books under your bed; if some of your most ridiculous, irresponsible choices have turned out to be some of the best decisions you've ever made; if your path into so-called adulthood has been more meandering and counterintuitive than fast-tracked, then this is a book for all of you, my darlings. And as for those graceful individuals who swanned themselves effortlessly into adulthood, you, too, might find something that interests you, even if it's just a juicy bit of voyeurism.

I have spent the past decades alternately fighting off adulthood with the gusto of a pack of Lost Boys forever partying down in Neverland, and timidly, awkwardly, earnestly stumbling toward the life of a grown-ass woman: healthy, responsible, self-aware, stable. At forty-three years old, I think I've finally arrived, but my path has been via many dark alleys and bumpy back roads. Along the way I've managed to scrawl a slew of booksâmemoirs about growing up a persecuted Goth teen in a crappy town, or a love-crazed party person getting my heart smashed up again and again; about the creepy secrets my family was harboring; about my time working in the sex industry. That I got these books published was a shockerâI hadn't gone to college or studied writing or anything. That people read them, and liked them, felt like a total miracle. Because of these books I've been able to cobble together something of an adult life,

writing and producing literary events, blogging and running a nonprofit of my own creation.

It is from this somewhat trembling, hard-won perch of adulthood that I type to you now. I type to you from a marginally clean homeâno longer do roaches scamper under cover of darkness! No longer do stubbed-out cigarette butts stud my floors! No longer will hungover twentysomething roommates vomit in

my

toilet! I type to you as one who has, amazingly, learned to fix my “broken picker”âyou know, the terrible radar that sends a person fluttering in the direction of the cad most likely to trample your heart. After a lifetime of flat-broke-ness that includes many dips into full-on poverty, there is enough cash in my bank account to occasionally blow on pricey perfumes and other useless but beautiful items. And, after nearly killing my life with drugs and alcohol, I have more than a decade sober, and all the oddball spiritual wisdom that comes with it. After a lifetime spent writing memoirs that detail the struggles that I and countless other girls experience when they're born broke, or weird, into tricky families and unsafe towns, it seemed like time to write a book about how that struggle can actually, with luck and grit, lead you straight into a life you didn't know you wanted and never thought you'd have.

Getting from there to here is a story that will take us to Paris Fashion Week and the punishing halls of blue-collar all-girl Catholic high schools; to the bingo games of Las Vegas casinos and a New England bus station where an Internet-sourced date peddled her pills; from a yacht on the French Riviera to a run-down San Francisco apartment with a persimmon tree in the

backyard; from Buddhist meditation halls to the magnificent Pacific Ocean. Like life, these tales rise up out of nowhere and leave you shaking your head and changed from the experience. Through repeat failures and moments of bruised revelation, I have mastered the art of doing things differently and getting different results. If you can't quite relate, I do hope you enjoy the wild ride. And if you do relate, I hope that what I've lived and what I've learned serve to make your own messy journey to adulthood a little less rocky, a little less lonely. At the end of it all, we're all just kids playing dress-up in our lives, some a little more convincingly than

others.

You Deserve This

I

chose the apartment because of the persimmon tree outside the bedroom window.

I haven't always selected my residences based on special magical detailsâmore like, if I was lucky to score a room in an apartment that was a cheap-o price, I snagged it. Never mind if people were shooting up between the cars parked outside my door, or if an anal yet ambitious roommate attempted to charge me an hourly rate for the housekeeping she did (true stories). Never mind if a nation of cockroaches scattered when a light flicked on and roommates responded to my horror with a snotty directive to “learn to cohabit peacefully with another species” (true story). Never mind if the shower was a tin can with a floor so rusted that one had to stand upon a milk crate in a pair of Tevas in order to bathe (like everything you will read in this book, true, true, true). This was the landscape of my twenties. I was flat broke and planned on spending the rest of my life as an

impoverished writer; cheap rent was a must. I was a little funny-looking, with tattoos sprawling across my body; choppy, home-cut hair that was dyed a color not found in nature; and thrifted clothes that fit strangely and bore many holes and stains. If all this was overlooked and I was permitted entry to a household, it was always in my best interest to grab it, roaches and rotting showers be damned.

In my twenties I spent seven years living in the Blue House, a crumbling Victorian so infamous for its lawlessness and squalor it had its own name, and its name was legend. The rent was ridiculously cheap, cheap enough for even the worst slacker/artist/alcoholic/addict to scrounge it up without having to clean up their lives too much. And speaking of cleanâwe didn't, as a rule, and we would state this as baldly as possible to new roommates. “You don't clean?” a prospective cohabitant would ask, a bit incredulous.

“Just look around,” I would invite them. Cigarette butts covered the floor, mashed there by a shoe, as if it were not a house but a bar after closing, before the cleaning crew came in. The beer cans and bottles rolling into the corners also suggested not a home but a tavern, or alternately, a frat house. Dishes were stacked in the sink, unless they were stacked in the bathtub, where they were piled when the sink stack rose too high. Heaps of trash bags mounded at the top of the stairs, where feng shui practice suggests you have an altar to peacefully greet you as you arrive home. And the kitchen floorâhow interesting, the potential cohabitants probably thought, to see a mud floor in an American home in 1997! How unexpected! But no, it was not an

actual mud floor; we simply hadn't cleaned the kitchen in quite a while. We were busy doing other things,

man

! Like, um, getting drunk! And in my case, at least, writing a book about it.

Although the Blue House was by any standard a total wreck of a place, it served me well. I simply didn't know how to take care of myself in my twenties. I was feral, and I needed a feral cave that allowed me to live in my simple ways. Because my rent was cheap, I didn't have to work very hard, and because I wasn't spending all my time at a J-O-B, I had plenty of time to write, and I did. I woke hungover every morning (okay, well, afternoon) and would wobble down to the bagel shop to spend the next four hours scribbling into notebooks. I wrote my first few books in this way, back when my alcoholism was, as they say, “working.” Sure, there were consequences, but I lived so low I didn't notice them. In fact, my low living

was

a consequence of my drinking, but I didn't see that then. I just saw, and felt, the thrill of the constant party. So there were some nights spent with my head in the toilet, some baffling inebriated fights with lovers and friends, some roaches in the kitchen. There were also my notebooks, filling up and piling up, and the exhilarating feeling that I was

living

.

I'd missed out on the East Village in the eighties, that heyday of decadent art and culture. I felt like I was getting a second chance in the Mission District of 1990s San Francisco.

At the dramatic finale of that wild decade, I hooked up with a man I would spend the next eight years with. Or, to be real, a man-child. He was nineteen years old when I met him, a Teen Poetry Slam champion. He moved straight from his parents' house into my own squalor palace, much to the alarm of my

roommates, who I'd believed were beyond feeling alarmed about anything. I guess even a punk house has its limits, and a jobless teen slumped on the couch watching

Unsolved Mysteries

and smoking pot all day is one of them. I was twenty-nine, coming down from my Saturn return, that infamous, dreaded moment when, if you believe in astrology, you feel the often brutal effects of Saturn, planet of limits and responsibility, returning to the place it sat at your moment of birth. This completion of the planet's orbit around the sun syncs up with the end of your twenties. It also roughly corresponds to the frontal lobe of your brainâthe place that comprehends risk and empathyâfinally developing. The frontal lobe gets damaged by alcohol abuse, so maybe that was why, so close to the moment when one is meant to comprehend her limits and get her shit together, I embarked upon a long-term cohabitation with a teenager.

When he and I moved out of the Blue House at the end of my seventh year in residence, I hadn't expected that it would be the start of eight years of house hopping together. But the both of us were a mess, and it was easier to scan our low-rent apartments and declare, “Thisâthis is the reason we are so miserable,” than to look at the root causes of our unhappiness

.

It was as if each new apartment would elicit from us the harmony we lacked, each new house key a metaphorical key, too, the elusive key to making this thing work. Maybe here we would stop squabbling like children. Maybe here my boyfriend would find a job he wasn't compelled to quit, bringing in some grown-up income. Maybe here would be the place where I would stop agonizing over whether mine was an “unhealthy relationship,” stop

daydreaming about running away with whatever doe-eyed creature happened to glance my way on the bus.

Our first apartment was a studio plagued with roaches; our next one was so crooked that fallen items rolled south. Eventually we scored an apartment that had not a single strike against itâit was clean and spacious, affordable, and bug-free. Of course, we needed a roommate in order to make rent, and so we endured a parade of lunatics to make it work: the compulsive liar who smuggled a pet Chihuahua into the apartment, as if we wouldn't hear it barking; the guy whose girlfriend left strange notes in the common spaces hysterically declaring how super sexy he was, as if she needed us to be aware of their powerful amour; my boyfriend's twin sister, the both of them engaging in the sort of psychotic fighting that only twins from dysfunctional families engage in. Our final home was in San Francisco's Italian North Beach neighborhood. It was as if the clouds had parted and angels had shoved it out of heaven and onto busy Columbus Avenue, bustling with tourists and the young Italian men who worked the restaurants, Chinese grandmothers clutching pink bags of produce, and drunkards on their way to the strip clubs over on Broadway. The North Beach apartment held such promise: no roommates, but bigger than a studio; two bedrooms, yet affordable enough that even I with my freelancer's erratic income and my boyfriend with his underachiever's erratic employment could make rent, no problem. Sure, our building manager, Mr. Fan, strangled ducks for dinner on his back porch right behind our bedroom. But he was always handy with a set of keys when I locked myself out, and I supposed I preferred witnessing the

occasional murder of waterfowl to participating in the daily murder of verminâour new little apartment was bug-free.

The special magical detail of this apartment was the old-fashioned funeral band that played outside the mortuary across the street each weekend. At first, we were both enchanted by it. The apartment would suddenly fill with horns and drumsâ“Amazing Grace” and some wrenchingly dramatic melodies lifted from Italian opera. The sound would invade the space and, just as abruptly, be gone, like a plane traveling overhead. It was so majestic that we forgot it was in honor of someone's passing.

Anyone who believes in omens knows that a funeral band and a procession of mourners outside your window every weekend is not a good one. The songs were like odes to this dying relationship, one I'd started nearly a decade ago. A lot had happened since then. I'd gotten sober, hadn't had a drink in years. I'd gotten published, and a photographer from the daily news came to take my picture. He snapped my photo against a brightly painted mural in my neighborhood, the wind blowing my hair around, a chunky strand of fake pearls around my neck. In the picture I'm looking off in the distance, as if at my own futureâwhich, now that I was sober, I actually had a shot at. I'd felt so old before I'd quit drinking. The damage and drama that accompanies a downward spiral weighs on your body and mind like age. The longer I stayed sober, the younger I felt, as if emerging from a chrysalis.

Even though my boyfriend had also gone through significant changes during our eight years together, eventually dealing with his own addictions, our personal transformations hadn't made

our relationship any easier. I'd read somewhere that people's patterns are established very early on, and if that's the case, my ex and I had gotten off to some brutally bad starts, back when I was still drinking and he was a deadbeat teen. But for eight long years we continued. And at the end of every fight, when we made up, we would dissect what had happened and feel like we'd solved the mysteryâthe mystery of why, when we loved each other so much, we couldn't get along. Armed with knowledge, we'd pledge to never, ever do it again.

But of course it would happen again. All of it.

Our apartment in North Beach should have been the best everâboth of us the best, sober versions of ourselves, living without the annoyance of other people. Playing house. But our days began in anxiety and too often ended with me crying and us making promises of peace we seemed incapable of keeping.

By the end, I knew one thing for sure. Whatever relationship you are in right now,

that

is the relationship you're in. You're not in the future awesome relationship that may never happen. You're not in the possibility of it; you're in the reality of it. When my ex brought his mother to help move his stuff out, I sat downstairs at the French patisserie and ate my feelings. I promised myself that I wouldn't let the dream of a better, more harmonious connection allow me to stay in an exhausting relationship ever again.

I wanted to make my life work in that North Beach apartment, solo. Living alone sounded great in my mind, the epitome of adulthood. But that house felt haunted to me now, empty, lacking the ruckus of my and my boyfriend's habitsâour fights,

sure, and the blaring of his reality television shows, but of our laughter, too, and our conversations. The silence was creepy. I barely used the kitchen, just snacked at the table. I never watched the TV, so there was no reason to sit on the futon. The little room I'd kept as an office, a tiny spot of privacy and quiet, was unnecessary now that the whole place was so private, so quiet. Not even the bedroom was a comfort; I'd paid for the mattress but had allowed my ex to select it, and it was hard as a rock to accommodate his aching back. I didn't want to be a grown-up if it meant being lonely and isolated, living in a tiny haunted house.

I put the word out to the people around me that I was looking for a new place in my old stomping ground, the Mission. I knew the chance of finding another affordable apartment to live in alone was unlikely in San Francisco with my fluctuating writer's income. I was in a tender, lonely state from the demise of my relationship. Even though it had been no good, we'd worked so hard and for so long. When I shared about it at a support group, an older, gray-haired woman took my hand. “It's like a death,” she said knowingly.

Maybe roommates wouldn't be so bad, I thought. Maybe it would be nice to not be the only body in a house, stuck with my downer thoughts and aching heart. Maybe being a grown-up wasn't about the total independence of living alone, capable of paying 100 percent of the bills yourself. Maybe being a grown-up could be more about knowing what you really need and letting yourself have it. Even if what you need is to live in a household full of people half your age, in a bedroom meant to be a dining room, with a window that looks out onto the most beautiful, fiery

persimmon tree you have ever seen in your life. Have you ever seen a persimmon tree? As all the other trees lose their leaves and begin their winter dying, the persimmon flares up brighter than any of them have ever been, bearing fruit, even. That was me. I wasn't on the same timetable as the other trees in the garden, but I was alive, coming into a certain prime, even. It wasn't starting over, no. It was just the newest chapter.

So, at thirty-seven, the most adult I'd ever been, I moved into a home that looked suspiciously like a lighter, slightly cleaner version of the Blue House.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

Know what's a grown-up thing to do? Having movers move your shit for you. It cost me three hundred dollars for a trio of dudes to come and heft my vintage kitchen table, my flea market desk with the Bakelite handles, and my boxes and boxes and boxes of books from my apartment in North Beach to my new home in the Mission.

My new roommate Bernadette, a twentysomething writer, stood at the top of the stairs as the movers lugged my belongings into the house. “It's so cool that you're moving in,” she gushed. “You have furniture!” In the kitchen, my yellow Formica table gleamed, the only piece of furniture in the room.

Bernadette took me on a tour. She brought me to the back door off the kitchen, where shambly stairs led to a tiny yard crammed with a billion plants that had gone to weedy seed in cracked pots and sawed-off milk jugs.

“The hoarder who lives in the garage took over the yard,”

Bernadette explained. “But people hang out here on the stairs. And smoke, obviously.” She pointed to a dessert plate being used as an ashtray. There were so many spent cigarettes on it that at first glance, it didn't look like an ashtray at all. A grotesque installation, it resembled a Bloomin' Onion from the Outback Steakhouse, a circular configuration of butts rising out from the plate. It was absolutely disgusting, if somewhat fascinating.