How to Live (19 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

Do not seek to have everything that happens happen as you wish, but wish for everything to happen as it actually does happen, and your life will be serene.

One should be able to accept everything just as it is, willingly, without giving in to the futile longing to change it. Montaigne seemed to find this trick easy: it came to him by nature. “If I had to live over again,” he wrote cheerfully, “I would live as I have lived.”

But most people had to practice it, and this was where the mental exercises came in.

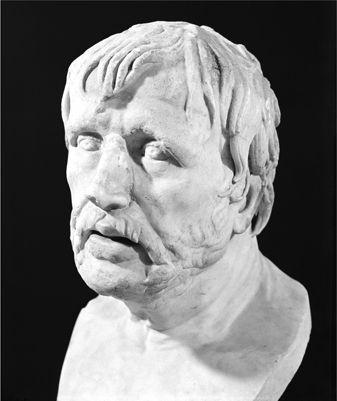

Seneca

(illustration credit i6.1)

Seneca had an extreme trick for practising

amor fati

.

He was asthmatic, and attacks brought him almost to the point of suffocation. He often felt that he was about to die, but he learned to use each attack as a philosophical opportunity. While his throat closed and his lungs strained for breath, he tried to embrace what was happening to him: to say “yes” to it. I

will

this, he would think; and, if necessary, I

will

myself to die from it. When the attack receded, he emerged feeling stronger, for he had done battle with fear and defeated it.

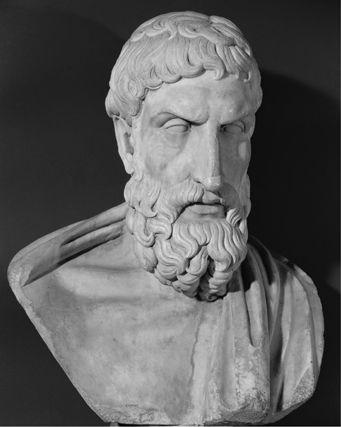

Stoics were especially keen on pitiless mental rehearsals of all the things they dreaded most. Epicureans were more inclined to turn their vision away from terrible things, to concentrate on what was positive. A Stoic behaves like a man who tenses his stomach muscles and invites an opponent to punch them. An Epicurean prefers to invite no punches, and, when bad things happen, simply to step out of the way. If Stoics are boxers, Epicureans are closer to Oriental martial arts practitioners.

Epicurus

(illustration credit i6.2)

Montaigne found the Epicurean approach more congenial in most situations, and he took their ideas even further. He claimed to envy lunatics, because they were always mentally elsewhere—an extreme form of Epicurean deflection. What did it matter if a madman’s idea of the world was skewed, so long as he was happy? Montaigne retold classical stories such as that of Lycas, who went about his daily life and successfully held down a job while believing that everything he saw was taking place on stage, as a theatrical performance.

When a doctor cured him of this delusion, Lycas became so miserable that he sued the doctor for robbing him of his pleasure in life. Similarly, a man named Thrasylaus nurtured the belief that every ship that came in and out of his local port of Piraeus was carrying wonderful cargoes just for him. He was happy all the time, for he rejoiced each time a ship came safely to port, and did not seem to worry that the cargoes never materialized. Alas, his brother Crito had his delusion treated, and that was the end of it.

Not everyone can have the benefit of being insane, but anyone can make life easier for themselves by turning down the beam of their reason slightly. With grief, in particular, Montaigne learned that he could not recover simply by talking himself out of it. He did try some Stoic tricks, and he was not afraid to focus his attention on La Boétie’s death long enough to write his account of it. But most of the time he found it more helpful to divert his attention to something else altogether:

A painful notion takes hold of me; I find it quicker to change it than to subdue it.

I substitute a contrary one for it, or, if I cannot, at all events a different one. Variation always solaces, dissolves, and dissipates. If I cannot combat it, I escape it; and in fleeing I dodge, I am tricky.

He used the same technique to help others. Once, trying to console a woman who was (unlike some widows, he implies) genuinely suffering grief for her dead husband, he first considered the more usual philosophical methods: reminding her that nothing can be gained from lamentation, or persuading her that she might never have met her husband anyway. But he settled on a different trick: “very gently deflecting our talk and diverting it bit by bit to subjects nearby, then a little more remote.” The widow seemed

to pay little attention at first, but in the end the other subjects caught her interest.

Thus, without her realizing what was happening, he wrote, “I imperceptibly stole away from her this painful thought and kept her in good spirits and entirely soothed for as long as I was there.” He admitted that this did not go to the root of her grief, but it got her through an immediate crisis, and presumably allowed time to begin its own natural work.

Some of this came from Montaigne’s Epicurean reading; some from his own hard-won experience. “I was once afflicted with an overpowering grief,” he wrote, clearly thinking of La Boétie.

It could have destroyed him had he relied only on his powers of reason to rescue him. Instead, understanding that he needed “some violent diversion,” he managed to develop a crush on someone. He does not say who, and it seems to have been insignificant, but it gave his emotions somewhere to go.

Similar tricks worked for another unwelcome emotion, anger: Montaigne once successfully cured a “young prince,” probably Henri de Navarre (the future Henri IV), of a dangerous passion for revenge. He did not talk the prince out of it, or advise him to turn the other cheek, or remind him of the tragic consequences that could result. He did not mention the subjects of anger or revenge at all:

I let the passion alone and applied myself to making him relish the beauty of a contrary picture, the honor, favor, and good will he would acquire by clemency and kindness.

I diverted him to ambition. That is how it is done.

Later in his life, Montaigne used the trick of diversion against his own fear of getting old and dying. The years were dragging him towards death; he could not help that, but he need not look at it head-on. Instead, he faced the other way, and calmed himself by looking back with pleasure over his youth and childhood. Thus, he said, he managed to “gently sidestep and avert my gaze from this stormy and cloudy sky that I have in front of me.”

He became such a connoisseur of side-stepping techniques that he even found political sleight-of-hand admirable, so long as it was not used to support tyranny. One story he relished was that of how Zaleucus, prince of

the Locrians of ancient Greece, reduced excessive spending in his realm.

He ordered that any woman could be attended by several maids, but only when she was drunk, and that she could wear as many gold jewels and embroidered dresses as she liked, if she was working as a prostitute. A man could sport gold rings if he was a pimp. It worked: gold jewelry and large entourages disappeared overnight, yet no one rebelled, for no one felt they had been forced into anything.

From his own experience of nearly dying, Montaigne would learn that the best antidote to fear was to rely on nature: “Don’t bother your head about it.”

From losing La Boétie, he had already discovered that this was the best way of dealing with grief. Nature has its own rhythms. Distraction works well precisely because it accords with how humans are made: “Our thoughts are always elsewhere.” It is only natural for us to lose focus, to slip away from both pains and pleasures, “barely brushing the crust” of them. All we need do is let ourselves be as we are.

Montaigne took from his Stoic and Epicurean reading what worked for him, just as his own readers would always take just what they needed from the

Essays

without worrying about the rest. For his contemporaries, this meant seizing on his most Stoic and Epicurean passages. They interpreted his book as a manual for living, and hailed him as a philosopher in the old style, great enough to stand alongside the originals. His friend Étienne Pasquier called him “another Seneca in our language.”

Another friend and colleague from Bordeaux, Florimond de Raemond, extolled Montaigne’s courage in the face of life’s torments, and advised readers to turn to him for wisdom, especially about how to come to terms with death. A sonnet by Claude Expilly, published with a 1595 edition of Montaigne’s book, praised its author as a “magnanimous Stoic” and spoke warmly of his manly way of writing, his fearlessness, and his ability to give strength to the weakest of souls. Montaigne’s “brave essays” will be praised for centuries to come, Expilly wrote, for—like the ancients—Montaigne teaches people to speak well, to live well, and to die well.

This provides the first inkling of the transformations Montaigne would undergo in his readers’ minds over the centuries, as each generation adopted him as a source of enlightenment and wisdom. Each wave of readers found in him more or less what they expected, and, in many cases, what they

themselves put there. Montaigne’s first audience was a late Renaissance one, filled with neo-Stoics and neo-Epicureans fascinated by the question of how to live well, and how to achieve

eudaimonia

in the face of suffering.

They embraced him as one of themselves, and made him a best seller. They thus laid the foundations for all his future fame as a pragmatic philosopher, and as a guide to the art of living.

Montaigne’s trick of absorbing La Boétie into himself, as a kind of ghost or secret sharer in all he did, might seem to run counter to his plan of distracting himself from grief. But in its way, it

was

a form of diversion: it led him away from thoughts of loss towards a new way of thinking about his present life. A split opened up between his own point of view and the one he imagined La Boétie might take, so that, at any moment, he could slip from one to the other. Perhaps this is what gave him the idea that, as he wrote elsewhere, “We are, I know not how, double within ourselves.”

Montaigne himself remarked that he might not have written the

Essays

had this space not been opened in himself. Had he had “someone to talk to,” he said, he might only have published letters, a more conventional literary format. Instead, he had to stage his and La Boétie’s dialogue within himself. The modern critic Anthony Wilden has compared this maneuver to the master/slave dialectic in the philosophy of G. W. F. Hegel: La Boétie became Montaigne’s imaginary master, commanding him to work, while Montaigne became the willing slave who sustained them both through the labor of writing. It was a form of “voluntary servitude.” Out of it emerged the

Essays

, almost as a by-product of Montaigne’s trick for managing sorrow and solitude.

La Boétie’s death certainly did leave Montaigne with some literary slavery of a more down-to-earth kind, in the form of his stack of unpublished manuscripts. These were not particularly unusual or original, with the exception of

On Voluntary Servitude

(assuming that this was indeed La Boétie’s work), but they deserved better than being left to crumble to dust. Whether because La Boétie had asked him to, or on his own initiative,

Montaigne now became his friend’s posthumous editor—a demanding role, which gave a push to his own literary career.

Rather surprisingly, considering his well-ordered character, La Boétie’s manuscripts seem to have been in a higgledy-piggledy state. In one of his dedications to the published work, Montaigne talks of having “assiduously collected everything complete that I found among his notebooks and papers scattered here and there.”

It was a formidable task, but he found many things worth publishing, including La Boétie’s sonnets. There were also translations of classical texts, such as the letter of consolation from Plutarch to his wife on the death of their child, and the first ever French version of Xenophon’s

Oeconomicus

, a treatise on the art of good estate and land management—a subject of relevance to Montaigne, who was just about to resign from Bordeaux.

Having sorted out the manuscripts, Montaigne saw a collected edition of them through the press. He traveled to Paris to liaise with publishers and to promote the result. For each of La Boétie’s pieces he courted a suitable patron, crafting graceful and sycophantic dedications to influential people including Michel de L’Hôpital and various Bordeaux notables—as well as to his own wife, in the case of the Plutarch letter. Conventional though the “dedicatory epistle” genre was, his letters are lively and personal. He also appended an even more personal piece of writing to the book: his account of La Boétie’s death. The whole undertaking confirms the sense that he was now in a literary partnership with La Boétie’s memory, and that the two of them could expect a great future together. It taught Montaigne a lot about the world of publishing and about what fashionable Parisians liked to read, information that would come in useful.