How to Live (26 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

Fortunately, Françoise herself was by no means ugly or repulsive. Montaigne seems to have found her attractive enough—or so his friend Florimond de Raemond asserted in a marginal note on a copy of the

Essays

. The problem lay more in the

principle

of being obliged to have regular sex with someone, for Montaigne never liked feeling boxed in. He fulfilled his conjugal duties reluctantly, “with only one buttock” as he would have said, doing what was necessary to beget children. This, too, comes from Florimond de Raemond’s marginal note, which, in full, reads:

I have often heard the author say that although he, full of love, ardor, and youth, had married his very beautiful and very lovable wife, yet the fact is that he had never played with her except with respect for the honor that the marriage bed requires, without ever having seen anything but her hands and face uncovered, and not even her breast, although among other women he was extremely playful and debauched.

This sounds appalling to a modern reader, but it was conventional enough. For a husband to behave as an impassioned lover to his wife was thought morally wrong, because it might turn her into a nymphomaniac. Minimal, joyless intercourse was the proper sort for marriage. In an essay almost entirely about sex, Montaigne cites the wisdom of Aristotle: “A man … should touch his wife prudently and soberly, lest if he caresses her too lasciviously the pleasure should transport her outside the bounds of reason.”

The physicians warned, too, that excessive pleasure could make sperm curdle inside the woman’s body, rendering her unable to conceive. It was better for the husband to bestow ecstasy elsewhere, where it did not matter what damage it caused. “The kings of Persia,” relates Montaigne, “used to invite their wives to join them at their feasts; but when the wine began to heat them in good earnest and they had to give completely free rein to sensuality, they sent them back to their private rooms.” They then brought on a more suitable set of women.

The Church was with Aristotle, the doctors, and the kings of Persia in this. Confessors’ manuals of the time show that a husband who engaged in sinful practices with his wife deserved a heavier penance than if he had done the same things with someone else.

By corrupting his wife’s senses, he risked ruining her eternal soul—a betrayal of his responsibility to her. If a married woman

must

pick up licentious habits, it was better to get them from someone who had no such duty. As Montaigne observed, most women seemed to prefer that option anyway.

Montaigne is amusingly wry on the subject of women, but he can also sound conventional. Unlike some contemporaries, however, he does not seem to have considered wives mere breeding cows. His ideal marriage would be a true meeting of minds as well as bodies; it would be even more complete than an ideal friendship.

The difficulty was that, unlike friendship, marriage was not freely chosen, so it remained in the realm of constraint and obligation. Also, it was hard to find a woman capable of an exalted relationship, because most of them lacked intellectual capacity and a quality he called “firmness.”

Montaigne’s opinion on women’s spiritual flaccidity can be disheartening enough to make one come over quite floppy oneself. George Sand confessed that she was “wounded to the heart” by it—the more so

because she found Montaigne an inspiration in other respects.

Yet one has to remember what most women were like in the sixteenth century. They were woefully uneducated, often illiterate, and they had little experience of the world. A few noble families hired private tutors for daughters, but most taught vapid accomplishments, as in Victorian times: Italian, music, and some arithmetic for household management. Classical education, the only kind considered worth having, was almost always absent. The few truly learned women of the sixteenth century were vanishingly rare exceptions, like Marguerite de Navarre, author of the collection of stories known as the

Heptameron

, or the poet Louise Labé, who (assuming she really existed, and was not a pseudonym for a group of male poets as one recent hypothesis suggests) urged other women to “lift their minds a little above their distaffs and spindles.”

France did have a feminist movement in the sixteenth century. It formed one side of the

“querelle des femmes,”

a fashionable quarrel among intellectual men who formulated arguments for and against women: were they, in general, a good thing? Those in favor seemed to have more success than those against, but such arch debate made little difference to women’s lives.

Montaigne is often dismissed as anti-feminist, but had he taken part in this

querelle

, he would probably have been on the pro-woman side. He did write, “Women are not wrong at all when they reject the rules of life that have been introduced into the world, inasmuch as it is the men who have made these without them.”

And he believed that, by nature, “males and females are cast in the same mold.” He was very conscious of the double standard used to judge male and female sexual behavior. Aristotle notwithstanding, Montaigne suspected that women had the same passions and needs as men, yet they were condemned far more when they indulged them. His usual perspective-shifting habits also made it apparent to him that his view of women must be as partial and unreliable as women’s views of men. His feelings on the whole subject are encapsulated in his observation: “We are in almost all things unjust judges of their actions, as they are of ours.”

Given such injustice, it is not surprising that he decided his own best policy at home was to absent himself from the female realm as much as

possible. He let them enjoy their kind of domesticity, while he enjoyed his. In an essay on solitude, he wrote:

We should have wife, children, goods, and above all health, if we can; but we must not bind ourselves to them so strongly that our happiness depends on them.

We must reserve a back shop all our own, entirely free, in which to establish our real liberty and our principal retreat and solitude. Here our ordinary conversation must be between us and ourselves, and so private that no outside association or communication can find a place; here we must talk and laugh as if without wife, without children, without possessions, without retinue and servants, so that, when the time comes to lose them, it will be nothing new to us to do without them.

The phrase about the “back shop,” or “room behind the shop” as it is sometimes translated—the

arrière boutique

—appears again and again in books about Montaigne, but it is rarely kept within its context. He is not writing about a selfish, introverted withdrawal from family life so much as about the need to protect yourself from the pain that would come if you lost that family. Montaigne sought detachment and retreat so that he could not be too badly hurt, but in doing so he also discovered that having such a retreat helped him establish his “real liberty,” the space he needed to think and look inward.

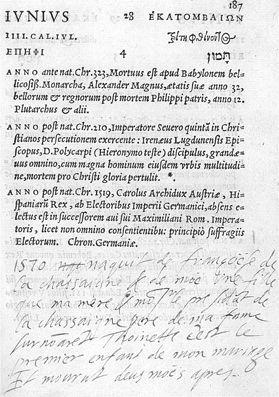

He certainly had reason to work at Stoic detachment. Having lost his friend, his father, and his brother in short order, Montaigne was now to lose almost all of his children—all daughters. He noted the sad sequence of births and deaths

in his diary, the Beuther

Ephemeris:

June 28, 1570: Thoinette. Montaigne wrote, “This is the first child of my marriage,” but later added, “And died two months later.”

September 9, 1571: Léonor was born—the only survivor.

July 5, 1573: Unnamed daughter. “She lived only seven weeks.”

December 27, 1574: Unnamed daughter. “Died about three months later, and was hastily baptized under pressure of necessity.”

May 16, 1577: Unnamed daughter; died after a month.

February 21, 1583: “We had another daughter who was named Marie, baptised by the sieur de Jaurillac councillor of

parlement

, her uncle, and my daughter Léonor. She died a few days later.”

Montaigne wrote that he had lost most of the children “without grief, or at least without repining,” because they were so young.

People generally did try not to get too attached to children while they were in early infancy, because the likelihood of their dying was great, but Montaigne seemed exceptionally good at staying aloof. It was an affliction he did not feel deeply, he admitted. He even wrote, in the mid-1570s, of having lost “two or three” children, as if uncertain of the figure, though this could just be his usual habit of vagueness about numbers. It is very much like his way of dating his riding accident, which he said happened “during our third civil war, or the second (I do not quite remember which).” In his dedication to his wife in the Plutarch translation, he gets the details even more startlingly wrong, writing that their first daughter had died “in the second year of her life,” although she died at two months. This was probably a slip of the pen

rather than of the mind. Or was it? One has the feeling, with Montaigne, that anything is possible.

There were other disasters in life that he knew would not bother him as much as they should:

I see enough other common occasions for affliction which I should scarcely feel if they happened to me, and I have disdained some, when they came to me, to which the world has given such an atrocious appearance that I wouldn’t dare boast of my indifference to them to most people without blushing.

One wonders if he was contemplating the possible death of his wife, here, or perhaps of his mother. If so, he had no such luck in either case. Or perhaps he was thinking back to the death of his father, or wondering what it would be like if his castle were sacked in the wars, or his lands burned. He seems to have found almost anything manageable other than the death of La Boétie: that was the one thing that knocked him off balance and made him unwilling to become so attached again.

In reality, his detachment is likely to have been less extreme than he pretended. His written notes of his children’s deaths are plain but poignant. And he could be eloquent about fatherly grief in the

Essays

—just not his own. His essay on sadness, written in the mid-1570s when he had already lost several children, dwells on stories of paternal bereavement in literature.

He also wrote feelingly about the ancient story of Niobe, who, after losing seven sons and then seven daughters, wept so much that she changed into a waterfall of stone—“to represent that bleak, dumb, and deaf stupor that benumbs us when accidents surpassing our endurance overwhelm us.” Whether or not it was losing his children that gave Montaigne this sensation, he surely knew what it felt like.

Montaigne failed in the main responsibility of a nobleman, which was to have a male heir to ensure the succession. But he did have one healthy child, Léonor, and he became fond of her as she grew beyond infancy.

Born in 1571, she must have been conceived not long after his ceremonial retirement in 1570. This made her the child of his midlife crisis and of his spiritual rebirth; perhaps it gave her that extra shot of life force. The sole

survivor, she lived until 1616, marrying twice and having two daughters of her own.

While she was growing up, her father gave her over mostly to the female domain, as he was supposed to. “The government of women has a mysterious way of proceeding; we must leave it to them,” he wrote, in a tone that suggests someone tiptoeing away from a place where he was not wanted.

Indeed, when he once overheard something he thought was bad for Léonor, he did not intervene because he knew he would be waved aside with derision. She was reading a book aloud to her governess; the word

fouteau

came up in the text—meaning beech, but reminiscent of

foutre

, meaning fuck. The innocent child thought nothing of it, but her flustered governess shushed her. Montaigne felt that this was a mistake: “The company of twenty lackeys could not have imprinted in her imagination in six months the understanding and use and all the consequences of those wicked syllables as did this good old woman by her reprimand and interdict.” But he kept silent.

He described Léonor as seeming younger than she was, even once she was of an age to marry. She was “of a backward constitution, slight and soft.” He thought this was his wife’s doing: she had sequestered the girl too much. But Montaigne also agreed to give Léonor an easy, pleasant upbringing like his own; he wrote that they had both decided she should be punished by nothing more than stern words, and even then, “very gentle ones.”

Despite his assertion that he had little to do with nursery life, other passages in the

Essays

do give us a charming picture of Montaigne

en famille

. He describes playing games together, including games of chance played for small amounts: “I handle the cards and keep score for a couple of pennies just as for double doubloons.”

And they amused themselves with word puzzles. “We have just now at my house been playing a game to see who could find the most things that meet at their two extremes,” such as the term “sire” as a title for the king and as a way of addressing lowly tradesmen, or “dames” for women of the highest quality and those of the lowest. This is not a cold, detached Montaigne, despiser of females and ignorer of children, but a family man, trying his best to play the genial patriarch in a home full of women who regard him most of the time with little more than exasperation.