How to Live (7 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

Thus, most of Montaigne’s thought consists of a series of realizations that life is not as simple as he has just made it out to be.

If my mind could gain a firm footing, I would not make essays, I would make decisions; but it is always in apprenticeship and on trial.

The changes of direction are partly explained by this questioning attitude, and partly by his having written the book over twenty years. A person’s ideas vary a lot in two decades, especially if the person spends that time traveling, reading, talking to interesting people, and practicing high-level politics and diplomacy. Revising earlier drafts of the

Essays

over and over again, he added material as it occurred to him, and made no attempt to box it into an artificial consistency. Within the space of a few lines, we might meet Montaigne as a young man, then as an old man with one foot in the grave, and then again as a middle-aged mayor bowed down by responsibilities. We listen to him complaining of impotence; a moment later, we see him young and lusty, “impertinently genital” in his desires. He is hot-headed and outspoken; he is discreet. He is fascinated by other people; he is fed up with the lot of them. His thoughts lie where they fall. He makes us

feel

the passage of time in his inner world. “I do not portray being,” he wrote, “I portray passing.

Not the passing from one age to another … but from day to day, from minute to minute.”

Among the readers to be fascinated by Montaigne’s way of depicting the flux of his experience was one of the great pioneers of “stream of consciousness” fiction in the early twentieth century, Virginia Woolf. Her own purpose in her art was to immerse herself in the mental river and follow wherever it led. Her novels delved into characters’ worlds “from minute to minute.” Sometimes she left one channel to tune in elsewhere, passing the point of view like a microphone from one individual to another, but the flow itself never ceased until the end of each book. She identified Montaigne as the first writer to attempt anything of this sort, albeit only with his own single “stream.” She also considered him the first to pay such

attention to the simple feeling of being alive. “Observe, observe perpetually,” was his rule, she said—and what he observed was, above all, this river of life running through his existence.

Montaigne was the first to write in such a way, but not the first to attempt to

live

with full attention to the present moment. That was another of the rules recommended by the classical philosophers. Life is what happens while you’re making other plans, they said; so philosophy must guide your attention repeatedly back to the place where it belongs

—here

. It plays a role like that of the mynah birds in Aldous Huxley’s novel

Island

, which are trained to fly around all day calling “Attention!

Attention!” and “Here and now!” As Seneca put it, life does not pause to remind you that it is running out. The only one who can keep you mindful of this is you:

It will cause no commotion to remind you of its swiftness, but glide on quietly … What will be the outcome? You have been preoccupied while life hastens on. Meanwhile death will arrive, and you have no choice in making yourself available for that.

If you fail to grasp life, it will elude you. If you do grasp it, it will elude you anyway. So you must follow it—and “you must drink quickly as though from a rapid stream that will not always flow.”

The trick is to maintain a kind of naive amazement at each instant of experience—but, as Montaigne learned, one of the best techniques for doing this is to write about everything. Simply describing an object on your table, or the view from your window, opens your eyes to how marvelous such ordinary things are. To look inside yourself is to open up an even more fantastical realm. The philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty called Montaigne a writer who put “a consciousness astonished at itself at the core of human existence.”

More recently, the critic Colin Burrow has remarked that astonishment, together with Montaigne’s other key quality, fluidity, are what philosophy should be, but rarely has been, in the Western tradition.

As Montaigne got older, his desire to pay astounded attention to life did not decline; it intensified. By the end of the long process of writing the

Essays

, he had almost perfected the trick. Knowing that the life that remained to him could not be of great length, he said, “I try to increase it

in weight, I try to arrest the speed of its flight by the speed with which I grasp it … The shorter my possession of life, the deeper and fuller I must make it.”

He discovered a sort of strolling meditation technique:

When I walk alone in the beautiful orchard, if my thoughts have been dwelling on extraneous incidents for some part of the time, for some other part I bring them back to the walk, to the orchard, to the sweetness of this solitude, and to me.

At moments like these, he seems to have achieved an almost Zen-like discipline; an ability to just

be

.

When I dance, I dance; when I sleep, I sleep.

It sounds so simple, put like this, but nothing is harder to do. This is why Zen masters spend a lifetime, or several lifetimes, learning it. Even then, according to traditional stories, they often manage it only after their teacher hits them with a big stick—the

keisaku

, used to remind meditators to pay full attention. Montaigne managed it after one fairly short lifetime, partly because he spent so much of that lifetime scribbling on paper with a very small stick.

In writing about his experience as if he were a river, he started a literary tradition of close inward observation that is now so familiar that it is hard to remember that it

is

a tradition. Life just seems to be like that, and observing the play of inner states is the writer’s job. Yet this was not a common notion before Montaigne, and his peculiarly restless, free-form way of doing it was entirely unknown. In inventing it, and thus attempting a second answer to the question of how to live—“pay attention”—Montaigne escaped his crisis and even turned that crisis to his advantage.

Both “Don’t worry about death” and “Pay attention” were answers to a midlife loss of direction: they emerged from the experience of a man who had lived long enough to make errors and false starts. Yet they also marked a beginning, bringing about the birth of his new essay-writing self.

MICHEAU

M

ONTAIGNE’S ORIGINAL SELF

, the one that did not write essays but merely moved and breathed like everyone else, had a simpler start. He came into this world on February 28, 1533—the same year as the future Queen Elizabeth I of England. His birth took place between eleven o’clock and noon, in the family château, which would be his lifelong home.

He was named Michel, but, to his father at least, he would always be known as Micheau. This nickname appears even in documents as formal as his father’s will, after the boy had turned into a man.

In the

Essays

, Montaigne wrote that he had been carried in his mother’s womb for eleven months. This was an odd claim, since it was well known that such a prodigy of nature was barely possible. Mischievous minds would surely have leaped to indelicate conclusions. In Rabelais’s

Gargantua

, the eponymous giant also spends eleven months in his mother’s womb. “Does this sound strange?” Rabelais asks, and answers himself with a series of tongue-in-cheek case studies in which lawyers were clever enough to prove the legitimacy even of a child whose supposed father had

died

eleven months before its birth. “Thanks to these learned laws, our virtuous widows may, for two months after their husbands’ demise, freely indulge in games of grip-crupper with a pig in the poke, heels over head and to their hearts’ content.” Montaigne had read Rabelais, and must have thought of the obvious jokes, but he seemed unconcerned.

No paternity doubts emerge elsewhere in the

Essays

. Montaigne even muses on the power of inheritance in his family, describing traits that had come down to himself through his great-grandfather, grandfather, and father, including an easygoing honesty and a propensity to kidney stones.

He seems to have considered himself very much his father’s son.

Montaigne was happy to talk about honesty and hereditary ailments, but was more discreet about other aspects of his heritage, for he came not from ancient aristocracy but, on both sides, from several generations of upwardly

mobile merchants. He even made out that the Montaigne estate was the place where “most” of his ancestors were born, a blatant fudge: his own father was the first to be born there.

The property itself had been in the family for longer, it was true. Montaigne’s great-grandfather Ramon Eyquem bought it in 1477, towards the end of a long, successful money-making life dealing in wine, fish, and woad—the plant from which blue dye is extracted, an important local product. Ramon’s son Grimon did little to the estate other than adding an oak- and cedar-lined path to the nearby church. But he built up the Eyquem wealth even further, and started another family tradition by getting involved in Bordeaux politics. At some point he gave up trade and began living “nobly,” an important step.

Being noble was not a

je ne sais quoi

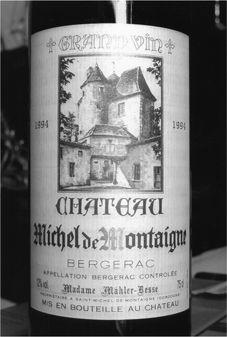

of class and style; it was a technical matter, and the main rule was that you and your descendants must engage in no trade and pay no taxes for at least three generations. Grimon’s son Pierre also avoided trade, so noble status fell, for the first time, on generation number three: Michel Eyquem de Montaigne himself. By that time, ironically, his father Pierre had turned the estate from a tract of land into a successful commercial concern. The château became the head office of a fairly large wine-producing business, yielding tens of thousands of liters of wine per year. It still produces wine today. This was

allowed: you could make as much money as you liked selling the products of your own land, without its being considered trade.

The Eyquem story exemplifies the degree of mobility then possible, at least towards the upper end of the social scale. New nobles sometimes found it hard to gain full respect, but this mainly applied to the so-called “nobility of the robe,” who were elevated for contributions to political and civil service, not to the “nobility of the sword,” who gained their status from property, as Montaigne’s family did, and prided themselves on the military calling that was expected to come with it.

Peasants, meanwhile, mostly stayed where they had always been: on the bottom. Their lives were still dominated by the local

seigneur

—in this case, the head of the Eyquem family. He owned their homes, employed them, and rented out the use of his wine press and bread oven. When Montaigne’s turn came along, he probably remained a typical

seigneur

from their point of view, however much he praised the peasants’ wisdom in the

Essays

—a book no agricultural worker on his estate was ever likely to read.

The entry on Montaigne’s birth in the family book states that he was born

“in confiniis Burdigalensium et Petragorensium”:

on the borders between Bordeaux and Périgord.

This was significant, for Bordeaux was mostly Catholic, while Périgord was dominated by supporters of the new religion, the Reformist or Protestant one. The Eyquem family had to keep its peace with both sides of a divergence that would split Europe in two throughout Montaigne’s life, and far beyond it.

The Reformation was still very recent news: its inception is generally dated to 1517, the year in which Martin Luther wrote a treatise attacking the Catholic tradition of selling fast-track earthly pardons or “indulgences,” and reportedly nailed it to the church door in Wittenberg by way of a challenge. Widely circulated, the treatise set off a major rebellion against the Church. The Pope responded first by dismissing Luther as a “drunken German,” then by excommunicating him. The secular powers of the Holy Roman Empire pronounced Luther an outlaw who could be killed on sight, thus making him a popular hero. Eventually most of Europe would fall into two camps: those who kept loyal to the Church, and those who backed Luther’s rebellion. There was never anything geographically or ideologically neat about this division. Europe fell apart like a crumbling loaf, not like an apple

halved by a knife. Almost every country was affected, but few went decisively one way or the other. In many places, especially France, the fault lines ran through villages and even families, rather than between separate territories.

Montaigne’s region of Guyenne (also known as Aquitaine) did show a pattern: roughly, the countryside went one way and the capital city went the other. Tensions were heightened by the general feeling, already widespread in the area before the Reformation, that Aquitaine did not form part of France. It had its own language, and few historical connections with the north of the country. For a long time, it had been English territory. The English were driven out only in 1451, by French invaders who were seen as alien and untrustworthy raptors. People harked back to the old era with nostalgia, not because they really missed the English, but because they so hated the northern French. Rebellions were frequent. The authorities built three heavy fortresses to keep the city under watch: the Château Trompette, the Fort du Hâ, and Fort Louis. All were hated; all are gone today.