How to Raise the Perfect Dog (10 page)

Read How to Raise the Perfect Dog Online

Authors: Cesar Millan

Tags: #Dogs - Training, #Training, #Pets, #Human-animal communication, #Dogs - Care, #General, #Dogs - General, #health, #Behavior, #Dogs

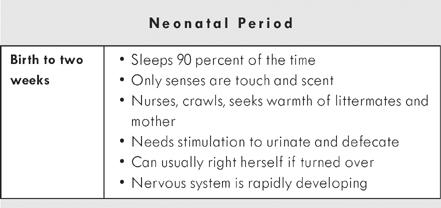

The First Two Weeks: The Neonatal Period

The First Two Weeks: The Neonatal Period

Puppies mature much faster than humans. The first two weeks of life for a puppy could be compared with an entire human infancy. But even at this helpless stage, the puppies are showing that they will fight to stay alive. Puppies may seem so tiny and helpless in this first phase of life, some uninformed humans will be reticent to handle them at all or to expose them to any undue stress during this time. The truth is, even in their newborn state, puppies’ brains are developing quickly and beginning to lay out the blueprint of how they will respond to and experience the world around them. Informed breeders like Brooke know that a carefully controlled program of handling at this stage is vital. It prepares puppies to be better problem solvers and to more effectively handle stressors, challenges, and new experiences later in life:

I want my puppies handled, so that having humans around them is a part of what they have always known. One of the first things I do is, I blow very gently on the puppies’ faces. I want them to associate my scent with nurturing, just like they associate their mother’s scent with nurturing. At one week of age, they get their toenails clipped, and again every week after that. I also let them experience the gentle blowing of a hair dryer from week one. Even though they can’t see or hear it yet, I want them familiar with its scent and the feeling of the warm air on them. Many of my puppies become show dogs, and I want grooming to be a part of their life routine right from the beginning, so it is never a foreign or upsetting event for them.

Like most responsible breeders, during the first two weeks, Brooke has a routine in place for handling her puppies a few times a day, for three to five minutes at a time, in order to accelerate their physical and psychological development.

1

When the puppies are three days old, Brooke brings in her vet to do a series of physical procedures. The first is tail docking, less common in other areas of the world but still standard procedure for show-quality miniature schnauzers in the United States. Brooke explains that this procedure—along with its frequent partner, ear cropping—didn’t originate for aesthetic reasons. These practices actually began as necessary operations for the survival of these working terriers when they were first “designed” 110 years ago.

2

“Miniature schnauzers were bred to rid barns in Germany of hordes and hordes of rats—not just one or two rats like we see in houses today, huge armies of them. If rats are together, they will launch a mass attack on a dog. If a dog has a long ear or a long tail, those places are vulnerable to attack. So originally, the ears and tail were taken care of strictly for practical reasons.”

During the same session, Brooke has the vet remove the puppies’ dewclaws. A dewclaw is something like a human thumb in its placement, but it grows a bit higher up on the paw than the rest of the toenails on that paw and never comes in contact with the ground. It’s a vestigial structure that is now nonfunctional or has some function only in some breeds—the sheep-herding Great Pyrenees, for instance, have double dewclaws on their back paws that were thought helpful for stability when herding sheep on rocky mountaintops. The majority of dogs have dewclaws only on their front paws. Dewclaws can hang loose, get caught, or cause minor or, rarely, serious irritations to the foot of a dog, particularly a terrier that is bred to dig. “Dewclaws on schnauzers are nothing but problems. It’s always the nail that they catch. So taking them out right away is something that we just do as part of the course,” says Brooke.

However, vets say that many dogs do just fine without having their dewclaws removed. When we think about removing something like a dewclaw on a puppy, we have to put it in the context of the fact that we have genetically engineered dogs away from their original design. Some features of the original design no longer function within the body of the new breed. Procedures like removing a dewclaw are the direct consequence of our having rearranged Mother Nature in the first place.

The most important thing to understand about your puppy’s first two weeks on the planet is that he is experiencing the world completely differently from the way a human baby would experience it. He knows three things—scent, touch, and energy. His mother is a scent, a warm body that provides comfort and food, but she is also a source of calm-assertive energy. She is gentle but definitely firm and assertive when she pushes a puppy away if she doesn’t want to nurse, or picks him up and moves him to where she wants him to be, or turns him over to clean him and stimulate his digestive system. She does not treat her litter as if they were breakable, and she does not “feel bad” if she needs to tell them in the language of touch and energy, “No, you are nursing a little too hard right now, back off.” Your puppy’s first experiences in life were filled with very clear rules, boundaries, and limitations.

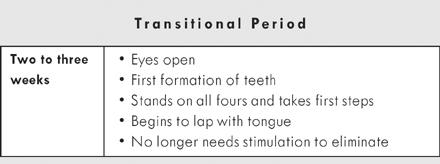

The Transitional Period: Weeks Two to Three

The Transitional Period: Weeks Two to Three

Between twelve and fourteen days, the puppies enter what is known as the transitional period, which lasts another week or so. Compared to human babies, their transition from infant to toddler occurs at lightning speed. The puppies will start standing on their wobbly little legs, jostling for position, and even begin to play dominance games with their siblings. They are more deliberate in their activities. And the bitch becomes noticeably firmer in her discipline and corrections. There is absolutely no time in the puppy’s early development that his mother is not modeling leadership and enforcing distinct rules, boundaries, and limitations.

This is also the phase that begins and ends with the puppy’s acquiring his final two senses. According to Brooke’s chart, Angel was born on October 18 and first opened his eyes on November 1. The landmark end of this stage in the puppy’s life occurs when he opens his ears—for Angel, that day was November 8, twenty-one days after his birth. A conscientious breeder will continue handling the puppies the way she did during the neonatal phase, and will also begin exposing them to different sights and sounds. For Brooke, this is the time when she allows outsiders—including future or prospective owners—to come to see the dogs. “I have ironclad rules about when people come down to visit the puppies. No shoes, and they always have to sanitize their hands. But I want my puppies handled. I want them to hear other human voices. And I want them to hear different sounds, like squeaky toys and the hair dryer. The vacuum is one that I insist on, because the vacuum is so terrifying to most dogs.” Having taken on

many Dog Whisperer

cases where dogs were terrified of vacuum cleaners and hair dryers, I can personally appreciate the hard work breeders like Brooke put into this early desensitization.

Like Brooke, Diana Foster can’t emphasize enough the importance of exposing puppies at this early stage to some of the different environmental sights, sounds, and smells they will be encountering once they’re out there in the “real world”:

Once the ears are open and they can hear a little bit, we do a lot of handling, picking them up, touching them, but we also start playing sound tapes. We do that at three weeks. We have realistic tapes of the sounds of firecrackers, vacuum cleaners, kids screaming, cars honking, doors slamming—everything you can think of from regular family life—because at that age, there’s no fear in the puppies yet. They have the comfort of their mother. We have the nice heat lamp on. They’re warm. They’re fed. They don’t shake. They don’t jump, and so what happens is, all these sounds get into their subconscious. This prevents the worst things that could happen down the line, like a German shepherd that gets freaked out when a kid yells. When that happens, the dog snaps at somebody. He ends up at the pound or being put to sleep, and it’s not even the dog’s fault.

By the arrival of their three-week milestone, Angel and his siblings were all walking around clumsily and responding to the sound of Brooke’s voice. They were about to enter what is probably the most significant time in a puppy’s early development, the socialization period.

Socialization: Weeks Three to Fourteen

Socialization: Weeks Three to Fourteen

These next six to nine weeks are among the most crucial in your puppy’s life, a time during which he will learn the lessons of how to be a dog among dogs, from his mother, littermates, and any other adult dog with which he is living. From weeks three to six,

3

puppies still interact primarily with their siblings and their mother. They will venture a few feet away from the mother or their “den” but quickly come running back. This first phase of the socialization period is the time of “becoming aware”—of their own bodies, their surroundings, their littermates, and the comfort of their mother.

The second phase of the puppy’s socialization, starting at about five weeks, is where the power of the pack comes in. His primary pack at this point consists of his mother and his littermates. Through trial, error, and an abundance of spirited playfulness, he learns from his littermates how to navigate through a social world. They teach him how hard he can bite or pounce, how to dominate, how to submit, and other basic skills of communicating with others of his kind. If your puppy were a canid being raised in the wild, the rest of the adult members of his pack would all jump in at this point and participate in making sure he grew up to be a good canine citizen. Canid societies—whether they be wolf, African hunting dog, or

Canis familiaris

—are incredibly orderly worlds in which the rules of the pack are established for every member, right from the beginning, with no exceptions. The whole pack adapts when puppies arrive, and they rearrange their lives to participate in the rearing. Even in the Dog Psychology Center, certain dogs in my ever-changing pack take it on themselves to become “nannies” or “schoolmasters” to any new pups or adolescents who happened to join our merry band.