How to Think Like Sherlock (14 page)

Read How to Think Like Sherlock Online

Authors: Daniel Smith

Jargon code

Here a seemingly arbitrary phrase is used in place of a known word or phrase. So, for instance, ‘The spider has spun his web from the queen to the Eiffel Tower’ might easily be read by a recipient in the know as ‘Professor Moriarty (the spider) has taken a train (has spun his web) from Victoria station (the queen) to Paris (the Eiffel Tower)’.

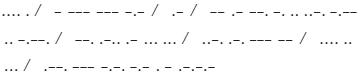

Morse Code

A remarkable code that may be rendered by long and short bursts of sound, flashes of lights, or written dots and dashes. Devised by Samuel Morse in the 1830s, it is still widely used today.

Cryptanalysis works by trying to establish a pattern in coded material. Once a pattern is recognised, breaking a cipher or code becomes achievable. One of the greatest weapons in the arsenal of the cryptanalyst is ‘frequency analysis’. This relies on the fact that in almost all languages, certain letters are used more frequently than others. As an example, e is the most common letter in English so there is a reasonable possibility (though not a certainty) that a symbol appearing most often in a ciphertext represents e.

Cryptanalysis is harder today than it has ever been, with new technologies allowing for more complex codes and ciphers. One of the most legendarily difficult to break was the Enigma code employed by German forces during the Second World War. The Enigma machine, a typewriter-like device, relied on a series of rotors that could be set in billions of combinations, allowing for plaintext to be delivered as seemingly impenetrable ciphertext. However, even this machine had weaknesses. A team of brilliant minds housed at Bletchley Park eventually broke the code. They were helped in part by frequency analysis, as they knew certain phrases (such as the names of German generals) recurred often in the encrypted messages. This gave the Allies a huge advantage in the war.

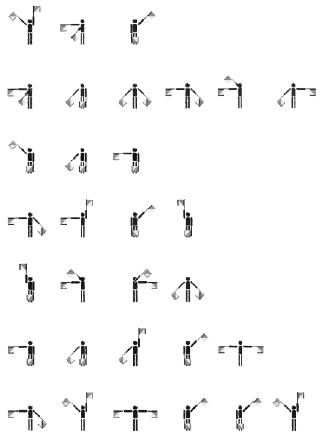

Given the complex challenges of cryptanalysis, it is little surprise that Holmes trained himself to excel at the art. As well as the monograph alluded to in the quote at the beginning of this section, he is witnessed breaking one word puzzle (in ‘The Musgrave Ritual’), three codes (in ‘The Adventure of the “Gloria Scott”’, ‘The Adventure of the Red Circle’ and

The Valley of Fear

) and the famous stick-figure cipher in ‘The Adventure of the Dancing Men’. See how well you get on with breaking the following codes:

Quiz 17 – Say What?

In each case, decipher or decode the devilish encryption!

1. 23,1,20,19,15,14 / 2,18,9,14,7 / 25,15,21,18 / 7,21,14.

2. Tifsmpdl Ipmnft nbef ijt efcvu jo B Tuvez jo Tdbsmfu.

3. Pd Imfeaz ime tue nqef rduqzp.

4. gt obrea kthi scod erequire sjus t abi to flatera lthinkin.

5.

6.

7. Heavy elephants learn pottery making enthusiastically.

8. A subtle plan is never discovered. Would Henry send his own man to help with the arduous money-bagging starting immediately.

Information Sifting

‘It is of the highest importance in the art of detection to be able to recognise out of a number of facts which are incidental and which are vital.’

‘SILVER BLAZE’

As Holmes amply illustrated, information may be gleaned from myriad sources. But once a body of relevant information has been accumulated, the next trick is to separate the wheat from the chaff: that which is truly useful and that which ultimately will lead you down a blind alley. The Great Detective was a master at streamlining his knowledge to suit his purposes. It is a lesson well-learned, especially for those of us living at a time when the prospect of drowning in a sea of data has never been greater.

There are plenty of real-life examples of information overload hindering a criminal investigation. Take the case of Peter Sutcliffe, The Yorkshire Ripper, who was convicted of killing thirteen women and attacking seven more in the North of England in the 1970s and 1980s. The investigation, undertaken at a time when computer technology was still in its infancy, was infamous for paperwork so mountainous that vital clues contained within it were missed. It was even reported that the floor of the main incident room had to be reinforced to deal with the weight of all the documentation. Furthermore, investigating officers wasted time on wild goose chases (such as investigating hoax audio tapes said to have come from the Ripper) while Sutcliffe slipped through their hands several times until his arrest and conviction in 1981.

Not even Holmes was immune to prioritising the wrong leads now and again. In ‘The Yellow Face’, he comes up with a theory about the case that ‘at least covers all the facts. When new facts come to our knowledge which cannot be covered by it, it will be time enough to reconsider it.’ Watson, though, calls it ‘all surmise’ and so it proves when Holmes is found to be far from correct in his assertions. Hindered in this case by the absence of vital information, Holmes failed to sift the data he did have correctly.

Here are a few suggestions as to how to sift your data more efficiently:

Have control over your data

That is to say, you must master it, rather than it you. Gather together all the information you have in as logical a system as you can. Wading through huge piles of information fragments is not conducive to effective sifting.

Keep an eye on the bigger picture

Always keep in mind the big puzzle that you are trying to solve when considering if you have a small piece of it in your hand.

Give yourself time and space to evaluate the information

Spending hours on end staring at data is not the best way to analyse it. Indeed, you might be one of those people whose optimum thinking is done in the shower or while going for a run.

Don’t be over-reliant on intuition

It is useful to have a gut-instinct about whether to trust one piece of information more than another. But beware of dismissing information on a whim. And always ask the question: do I have all the pertinent information?

Beware the ‘recency’ effect

We have a tendency to prioritise the information that we have most recently acquired. Recency and relevance are not inherently linked.

Retain the chaff

Until you have successfully worked through your ‘wheat’ and solved your conundrum, you may need to revisit the ‘chaff’ to see if there is anything you have missed.

The job of information sifting is easier if your note-taking powers are up to scratch. The secret to good notes, as any exasperated university lecturer will tell you, is not to take down verbatim accounts. Such an approach ensures that data will slip seamlessly in and immediately out of your brain. The trick is to actively engage with the material you are taking notes on, encode it in a way meaningful to you and reference it to your own knowledge. What does this mean in practice?

You must grasp the point of the information you are taking notes on.

Cut out any extraneous information as you note-take. For instance, if you are working from a textbook, you might begin by highlighting short passages that best carry the point of the text. Similarly, if you are taking notes while someone is speaking, you should not jot down their verbal ticks or detail long examples given to reinforce a simple point. By being selective in what you note down, you are engaging with the material and have already started the sifting process.