Hubbard, L. Ron

Authors: Final Blackout

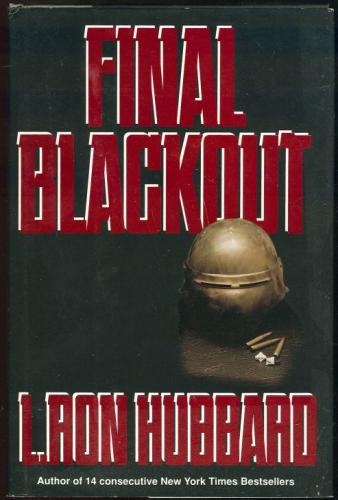

FINAL BLACKOUT

BY

L. RON HUBBARD

L RON HUBBARD BRIDGE PUBLICATIONS, INC. LOS ANGELES

FINAL BLACKOUT 0 1991 L. Ron Hubbard Library. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Earlier edition 0 1940 L. Ron Hubbard. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address Bridge Publications, Inc., 4751 Fountain Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90029.

FINAL BLACKOUT Dust jacket Artwork 0 1991 by L. Ron Hubbard Library

First Edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Hubbard, L. Ron (Lafayette Ron), 1911 - 1986

Final blackout 1. Fiction, American. 1. Title ISBN 0-88404-651-6 (alk. paper)

The men and officers with whom I served in World War II, first phase, 1941-1945.

Final Blackout is an extraordinary novel featuring an extraordinary hero

¯

"The Lieutenant." The Lieutenant is unforgettable.

Fictional heroes come and go constantly in literature. They do their brave deeds, save the world, and usually are displaced by the next hero on the bookshelves.

In real life, the history of the world shows that mere victory is not what makes the memorable leader. George Washington is not honored for winning battles

¯

he lost more than he won

¯

but for establishing an enduring free republic in a world which up to then was almost totally ruled by rigid aristocracies. Winston Churchill fought for Britain in combat as a young man., but that isn't why he's a pivotal figure in the outcome of World War II ... or what most people think was its outcome. And Mahatma Gandhi, who never fired a shot, then defeated Churchill's victorious British Empire and thus changed the course of history.

More than anything else Final Blackout offers importance. Under its fast-paced scenes of combat, passions, treachery and grim endurance in a war that never stopped, is its carefully developed, totally authentic portrait of The Lieutenant not as soldier but as strategist. Not as a merely military strategist though to the end he sticks to his guns

¯

but as a statesman. There's plenty of adventure in this book. But what The Lieutenant's spectacular career embodies is a down-to-basics description of why the world can be changed, why it only rarely changes for the better, and what that can mean for you and me. The book is populated by characters who would have been historical figures in what we call the real world. But as depicted in Final Blackout, their struggles for power hit sharply home to those of us who usually just have to put up with whatever history is doing to us whenever it wants to.

That's why this book and its hero have never been obscured since its first publication in a magazine, why many thousands have been reading various small editions of it over the years, why it's famous among those readers, and why this new large audience edition was created in response to added thousands who had heard of it and wanted it. Like The Lieutenant, it's an "unkillable: FINAL BLACKOUT"

Its author is an extraordinary person. L. Ron Hubbard (1911-1986) wrote it during that strange, brief era when the then Prime Minister of England was still issuing assurances of "peace in our time" and Hitler and Stalin, surely the two most numerically successful killers in history, were temporarily dividing up Europe preparatory to failing on each other. Final Blackout reached its first publication, as a three-part serial in a magazine called Astounding Science Fiction. By then, its author was within months of going off to fight in what some call World War II, what others see as the inevitable continuation of World War I, and which some can reasonably claim has never really come to a conclusion.

Astounding was the leading science fiction magazine of its day, propelled into prominence among those readers by a remarkable gathering of fresh new creative talents. L. Ron Hubbard was among the earliest of those, and. in their first rank. Unlike his contemporaries

¯

who would eventually include Robert A. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, A. E. van Vogt, and many other authors who are still legendary names in that field and beyond it

¯

Hubbard already had a powerful reputation in scores of popular fiction genres.

Years before his appearances in science fiction, he had begun as an adventure-story writer, and had then branched out to publish millions of words across almost the entire spectrum of newsstand fiction in its heyday. He was specifically brought in to lend the weight of his byline to the struggling Astounding, by its new publishers. Sales figures had convinced them L. Ron Hubbard's name on a magazine cover attracted thousands of added readers.

He quickly proved he could successfully transfer that magic to science fiction, and to fantasy in the sister publication Unknown. For his speed and productivity, and most important for his ability to deliver story after story that brought readers flocking, he almost overnight became a legend among legends. Some of his fellow authors even wrote stories in which he figured as a leading character, under thin disguises. All of them speak of him as a commanding figure, magnetic and full of gusto, standing at center-stage wherever these writers gathered in what has become known as the "Golden Age" of science fiction. He was a proven veteran of what was called "fictioneering," while most of them were yet novices ... and he was still in his twenties.

He was 28 when he wrote Final Blackout. He had already been the author of scores of impressive shorter pieces in the field, making himself swiftly at home in it. He had often demonstrated the ability to pioneer fresh approaches to this literature. But even for him, and even for Astounding, his first novel in that medium was a stunner.

A Preface he wrote for a postwar small-press book edition is reprinted here following this Introduction. It conveys the sense of the immediate reaction among science fiction readers and then the spreading, shockwaves of response from well beyond the boundaries of that readership.

With typical ironic humor, Hubbard "apologizes" for his naiveté in world politics and his "youthful ignorance" of the high ideals that actually govern the leaders of society. As a satirical commentary, that Preface all by itself would make this book well worth attention. Almost uniquely among his mid-century writings, it conveys the tone of his ultimate science fiction magnum opus, the ten volume Mission Earth novel of the 1980s. In its own way, it's rife with uncomfortably prophetic overtones as Final Blackout is in its way. The "young," "naive" L. Ron Hubbard had a disturbingly apt way of cutting through the pretensions of those who claimed to know best.

The novel by the man who was readying himself for a major war was provocative reading, infuriating to some. So is the Preface produced six years later by the man fresh from that war ... or from a major episode in that continuing war ... and no less clear-eyed about what the future held.

It could easily be argued that Final Blackout did not belong in the pages of a "mere' science fiction magazine. Part of the initial impact on Astounding readers must have arisen from its expertise in military tactics, its confident grasp of strategy and, beyond that, of the chicaneries behind making war in search of political power.

Other writers in the field could write convincingly of "future war"; Hubbard's novel, however, had the ring of extra truth in countless details that none of his contemporaries could display. What's more, it was written from a level of political sophistication that was not hinted at again in speculative literature until George Orwell's postwar Nineteen Eighty-Four ... a work which, of course, was too serious to first appear as a "mere" magazine serial. (Frankly, Hubbard's offering of an optimistic solution seems preferable to Orwell's cumulatively hopeless list of reasons why no solution is really possible.)

The answer to how the "young" Hubbard was able to bring this off is that he was uncommonly sophisticated and sharply educated in the best senses of those terms. Even when he began writing his earliest adventure stories, those were not based on armchair research but on personal experience in the wilder corners of the world. That experience in turn had been directed by his lifelong enthusiasm for learning new things and meeting new people, and trying out their ways himself.

Lafayette Ronald Hubbard was born in Nebraska but spent his earliest years in Montana, which even in the 1980s is still a place happily removed from many aspects of urban culture. In 1911, it was frontier in all but name.

He was raised at first by his grandparents, his father being a U.S. Naval officer on duty, and it's said he could ride before he could walk. Early in the second decade of his life he was both an Eagle Scout and a blood-brother to the Blackfeet Indian Nation. His first hard-cover novel, Buckskin Brigades, 1937, would graphically depict the ruinous impact of early fur-trading incursions on the Blackfeet. (On its recent republication in the Bridge edition, the Blackfeet Tribal Council addressed a letter of gratitude to his spirit.) (As the youngest Eagle Scout in the nation, Hubbard was introduced at the White House and made friends with the son of President Calvin Coolidge.)

Shortly thereafter, under the direction of his father and his father's connections, Hubbard in his teens began traveling beyond the borders of the U.S., studying formally and informally with a variety of experts in human psychology, engineering and the sciences, while getting ample opportunity to observe how the world works in places as diverse as China and the Caribbean.

In addition to then going on to sail expeditions into places in both hemispheres that were then considered exotic-and some of which still are-he became a member of The Explorers Club. On several occasions he carried on expeditions under their flag, becoming an expert on Alaskan waters and charting them. There are some indications that his private and quasi-private small-vessel activities in that area extended along the Aleutian Islands and southwestward, just as there are strong indications that he was being groomed and was grooming himself for something special in the way of Naval service. So there is good reason to believe in Hubbard's practical understanding of human nature, military lore, and political history. There is equally good justification for believing that the geopolitical concerns Final Blackout reflects were on his mind for practical reasons that went far beyond the needs of earning a living as a writer.

Certainly, when he formally entered the U.S. Navy in mid-1941, prior to Pearl Harbor, he did so under the auspices of a carefully worded April 8, 1941, letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt from Congressman Warren D.

Magnusson, head of the Naval Affairs Committee in the House of Representatives.

Hubbard was at sea enroute to duties in the Orient when the Japanese launched the war that many in and out of the U.S. military had been quietly expecting for some time. His actual military career is only now being reconstructed from documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, and from the testimony of former crew members on various vessels he commanded. (He appears to have known very well how to lead men, inspiring uncommon devotion and lifelong loyalty.)

He was also the Senior Naval Officer Present in Australia, gathering and directing supplies to General MacArthur's defense of the Philippines, before transferring to the Atlantic Fleet. His friend, Naval Academy graduate Robert A. Heinlein, has declared that Hubbard convalesced at his home from serious injuries that do not appear on the record released by the U.S. Navy after the war.

And if the Preface is pointedly ironic, that may well be related to the fact that Hubbard immediately after the war severed his connections to the Navy and soon thereafter began a new career-signaled by the release of Dianetics, The Modern Science of Mental Health-whose stated goal is the achievement of a sane planet. The dry wit visible in the Final Blackout Preface may not be all there is to this. Underneath, there may be a far deeper bite occasioned by experience in which Hubbard discovered that what he had written about as speculative fiction was very much like something all too true.

The haunting quality of Final Blackout can't now be separated from suppositions of that kind. When it was written, for instance, passages in which US. Marines are called in to suppress heroes were unheard-of in popular fiction. When they appeared in that marketplace, combat Marines were always the ultimate symbol of virtuous strength, fighting only on the side of pure right. Hubbard as a deft technician of writing was well aware of the value of "going too far" just far enough to titillate science fiction readers. He may have been doing no more than that. On the other hand, Hubbard may already have had reason to understand-as more of us do today-that the goodness and bravery of individuals can sometimes be put to dubious uses in high-level power-games conducted by world leaders.