I Am China (37 page)

Authors: Xiaolu Guo

She tries to finish reading Mu’s diary entry on the death of her father. Perhaps, witnessing one of your family members dying is a way of understanding death, as well as a way of overcoming the vanity of youth. Childhood is a kind of eternity, youth is the time of daybreak. And then … Iona imagines her mother’s death. She thinks of the dying process taking hold of her mother’s body. It has already begun: hair falling, flesh beginning to loosen from bones, the heart growing weaker,

like a slithering lizard scratching inside a box. But her imagination is running out of control. It’s only her mother’s sixtieth. Suddenly, a downpour of light flushes into the train; she peers at her serious face in the window, frowning, with an unsettled look. She feels a needling disturbance, but she also feels she has never been so steady and accepting of her own sense of anxiety. It’s like she can step back and look at herself, like watching a frightened animal. But as the shadow comes again, she wonders if her steadiness is just the coldness within her, rising up, like damp in a wall. Once the damp begins, you can’t stop it. Like a frozen shoulder joint, movement impossible.

The train stops in each town on the way north. Stafford, Stoke-on-Trent, Kidsgrove, Crewe, Preston, Lancaster, Carlisle. She’s not been anywhere; the names mean very little to her. She imagines Jian and Mu’s figures appearing, from time to time, in the midst of the hazy green fields. But their shadows are swallowed by the dark tunnels into which the train plunges headlong. As the train passes Glasgow, a steward pushing a trolley stuffed with snacks and drinks stops beside Iona. She turns and stares stupidly at the sweets and crisps and drinks; at a loss as to what to choose, she buys a chocolate bar and turns back to Mu’s diary.

In my peasant mother’s eyes the shipping tycoon Gu is Chairman Mao’s reincarnation, perhaps even more useful than Mao himself. Now, as I write, a London address is before me. And that address will be my new home—as a lodger in a flat in east London. Goodbye to my old life. Goodbye, China

.

14

ISLE OF MULL, SCOTLAND, OCTOBER 2013

When Iona gets off the ferry, the afternoon light is already waning. She carries her bag and her Chinese vase across the evening moorland. The earth is wet and spongy and her shoes sink into the muddy ooze. Her trousers get spattered. It must have been raining yesterday. She gazes at the clouds. The landscape seems already paralysed by the autumn chill. The grass is grey-brown, the island static, suspended in a gloomy blue-grey. In the near distance she can see a few cows in front of her parents’ stone house, silhouetted against the grey sky. Then she sees the old pine tree in front of the house.

It’s a black mountain pine, producing plenty of cones each year. She used to climb this tree when she was a moody little girl. And she would sit on the branches for a long time on summer afternoons; through the foliage she could see the sea, and in the distance the small island which bears her name: the Isle of Iona. And then she would speak to herself, to the little Iona inside her: “I want to see the world, I want to know everything about the world!”

Iona’s mother has prepared a familiar family dinner. Steamed broccoli, roast potatoes and roast beef. Her father is not at home. “He went to the Beak,” her mother says lightly. The Beak is Swan’s Beak, their local pub down the valley. It has been going strong for decades, a local haunt, and her father has frequented it since long before Iona was born.

“Is Nell not coming tomorrow?” asks Iona, noticing the kitchen is dim in the minutes before the last of the twilight fades to dark.

“She’s just too exhausted with the twins … and Volodymyr can’t get time off work this week …” Her mother looks a little despondent. “I’ll miss having the boys this year.” She staggers to her feet and seems about to trip, but steadies herself.

Iona notices her mother’s hand shakes a bit when she tries to open a bottle of whisky. She feels panicky—early symptoms of Parkinson’s disease? She says nothing.

The wind penetrates the windowpanes and agitates dust on the slate floor. It is only late October but it is freezing cold, though the heating is on and the fire is lit. Iona takes off her muddy shoes and sits beside the fire, adding more wood.

“Have you been to see the doctor recently, Mum?” Iona asks.

“I went last week. He said my arthritis is stable—no worse, no better. I just need to learn to live with it … and he gave me some sleeping pills.”

“Sleeping pills? Is that all he gave you?”

“Well, you know how it is; there’s not much to be done about my legs.”

Her mother takes another sip of whisky, her hands steadier now.

“Maybe you shouldn’t drink so much,” Iona says with a frown.

“It’s good for my joints and my blood,” her mother insists, as she always has done.

As usual, they don’t wait for the old man before starting supper. The three of them will have a big birthday breakfast tomorrow anyway. The two women sit at the kitchen table thoughtfully, the silence punctuated by windy shivers and the sounds of their eating. Iona adds some salt to her plate. The broccoli is hard, zesty, but too simple for her. She begins to feel they are goats feeding on roots on a rocky clifftop.

“Hmm, I steamed the broccoli, but it is still rather firm,” her mother mumbles apologetically. More silence and more chewing follows. The beef has been carved from a plate with a bloody pool of gravy. It has a real country heartiness, but there is no garlic, no spice, something Iona craves.

Outside, the highland world is quiet but for the wind and the occasional animal cry. As she watches her mother eat, a sad tenderness colours Iona’s heart. Iona remembers flavours from her childhood—strong, pungent, full of spice—and the energetic mother of those years

that this unhappy woman before her once was. When she was very young, her mother read her and her sister

The Little Mermaid

. She had cried when she learned that the mermaid had to cut off her exquisite tail to become a human so she could love a prince from the human world. And in the end the prince marries a human princess, leaving the little mermaid with her anguished heart and bleeding body, alone. Some years later, when Iona had her first period—the painful twist, like a screw inside her, bringing her to womanhood—she remembered the story again.

“Seeing any nice boys?” her mother asks, liberally sprinkling salt on the potatoes. They are a rich golden brown, crisp and buttery.

“Not really … I have met someone, but he’s a lot older … so, I don’t know.”

“Well, as long as he’s not your father’s age …” Her mother looks at her quizzically.

“No, not that old, Mum!” Iona feels anxious, a pause, she adds, “But I think he might be married.”

“Then you must get over him.”

“It’s not like taking an aspirin, you know.” Iona doesn’t even know what she feels for Jonathan exactly, but she won’t be told how to behave.

“Tell me, Iona, what is it?”

“What do you mean?”

“You know what I’m talking about. What is it you’re after?”

“I don’t know …” Iona tries to think of a word. “I feel like I’m looking for something—a certain aliveness.”

“Aliveness,” her mother murmurs, then sighs. It is not the first time the older woman has heard this curious term on her daughter’s lips. “That might have meant something to me once. At the moment, I’m just happy enough getting from one day to the next.”

“Oh, things aren’t that bad, are they?”

One, two, three, four, five, Iona counts, as she eats each potato. The rain is starting outside, carried by the sea wind. Her father is still not back from the pub. Iona remembers that when she was here having

dinner with her mother last time, she also had a plate of crispy roast potatoes. Next day, right after her morning porridge, she took the first morning ferry and got the train back to London.

“Mum …” Iona wipes her mouth and suddenly has a totally spontaneous idea—something grows from her guilt with this old farm and this old family. “You know what? Let me take you and Dad on holiday.”

“What?” Her mother’s eyes are wide open; she turns her head aside, thinking she might be mishearing words. “What? A holiday?”

“Yes, a holiday, Mum, you deserve a holiday, I want to arrange that for you and Dad …”

Her mother hasn’t left the island for a long time. “Really? Well, I don’t know, darling.”

“You could go somewhere warm and sunny.” Iona thinks, and improvises suggestions. “Crete, Mallorca, Cyprus … We can ask Dad when he comes back.”

Her mother smiles gently, as if listening to a radio programme she likes. It seems she doesn’t really mind whether it happens or not; just imagining being on holiday with her daughter is in itself a wonderful gift on her sixtieth birthday.

EIGHT | LAST DAYS IN CRETE

zhong gua de gua, zhong dou de dou.

Sow melon, reap melon; sow beans, reap beans

.

DONG ZHOU LIE GUO ZHI

, FENG MENGLONG (PLAYWRIGHT, MING DYNASTY, 1574–1646)

1

LONDON, NOVEMBER 2013

Above Chapel Market, Iona is nearing the end of her translation. There are two more pages to go of Jian’s diary.

I was ten years old. One day the school took us on a day trip to the seaside town of Qinghuang Island. It was the first time in my life that I had seen the sea. Blue. Blue was the colour I loved, just like this blue in front of me now, but I no longer care about this blue on this foreign ship with a foreign language I have never encountered before. That day my school friends and I played volleyball on the beach with the tide coming and going beneath our feet; we swam among the waves; we rolled in the sand; we found blue crabs under the rocks and we made a bonfire from driftwood; we cooked our catch of crabs and sang songs under the evening moon. I was with my “da jia”—my “big family”—all the Young Pioneer boys and girls, not even teenagers yet, laughing and crying together with joy. But the sea here, today, is different. It is totally desolate, devoid of the people I once knew, devoid of their laughter and cries

.

Now I think that was probably one of the happiest days of my life. I felt so free. I remember the soothing wind, the boundless sky, the daring seagulls wheeling overhead and then diving into the water and plucking fish from the waves … Nature was so great that day. Nature was much greater than my family, than my Beijing life, than everything I was taught and forced to learn. I wish I had remained forever in that moment. I belonged to it like the sand belongs to the beach, like the seagulls belong to the sea

.

And this morning I woke up with a single image in my head. I dreamed of the bluest sea I will ever see

.

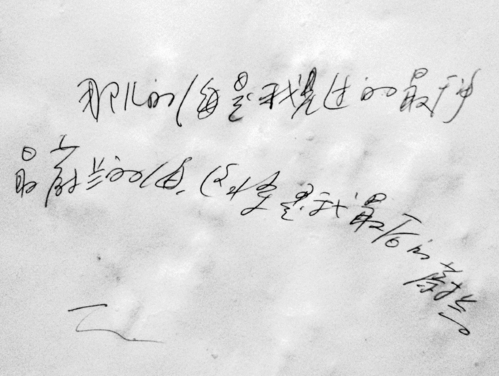

Iona turns to the next page of Jian’s diary. She is on the last page, there are no more photocopies in his file. On the white sheet, there are only two lines, scribbled with big characters. But the characters are sprawling out every which way and so messily written that they are nearly unrecognisable.

It takes her a while to make out each character and she has to hold the page at odd angles to try and decipher the words. Eventually she has a rough translation of Jian’s two final sentences:

The sea there is the bluest and purest. It’s the last blue I will see

.

There are no more words from Jian for her to translate, at least not from the files in front of her. Iona double-checks the whole package Jonathan gave her. There are a few unfinished poems from Mu that she hasn’t got to yet, but this is the last fragment in Jian’s scrawl. No dates, no location either. She returns to the page, murmurs and repeats

these two mysterious lines out loud in Chinese and then in English. There is something so simple, so enigmatic about this small fragment. The meaning is elusive. She tries to translate it a different way, unsure exactly what he meant.