I Am China (9 page)

Authors: Xiaolu Guo

7

DOVER, MAY 2012

Brandon walks through the gate of the Removal Centre with his pepperoni pizza and his watery coffee. Today he has bad news for Jian. He passes two blue-uniformed workers perched on a ladder, taking down the sign that says

Dover Immigration Removal Centre

. Up the ladder again and

Removal Centre

becomes

Detention Centre

. Brandon raises his eyes; heavy dark clouds drift across the sky. Rain is falling, instantly drenching the sign the workers have just put up.

One of the workers turns to his companion. “Detention or Removal—isn’t it the same thing? Most of the foreigners in this place are gonna be sent back. Right?”

Brandon walks on as raindrops pelt down, exploding in his hair and eyes, like gobs of pigeon shit. He scoots into the building for shelter.

Rain is battering the windows next to Jian. As Brandon breaks the news he hunches further over his world map, trying to dissolve into it. The UK authorities are closing the door to immigrants; nearly 90 per cent of applications will be refused, according to the new points-based system.

“Jian, you gotta understand, there’s nai more space for people in this country. This is not China!”

“How many people you got then?” Jian asks.

“Sixty million. That’s a laat for a wee island. It’s not like Switzerland, only got sieven million!”

It’s not like Switzerland, only got sieven million

. Like a breeze gently murmuring in Jian’s ears, the thought occurs to him that maybe it wouldn’t be so bad to live like a goat on the side of a Swiss mountain.

A mountain would be good enough, for a while at least. And this is what inspires Jian to write to Switzerland, a country that might be kinder than the Queen’s Land to someone like him.

“Do you know the address of the immigration office in Switzerland?” he asks eagerly.

8

LONDON, MAY 2013

The pile of letters before Iona seems to be a never-ending mystery—haphazardly organised, some dated, some not. Iona had assumed all the material was from Kublai Jian and it’s rather a surprise to find the letter she is reading now is written in a totally different style.

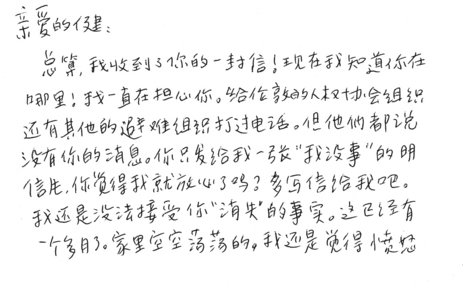

Unlike Jian’s letters and diary entries, messy to the point of indecipherable, the handwriting on the page in front of Iona is neat and clear, with elegant flourishes, touches of calligraphy even. A feminine hand; a woman’s voice. Indeed, it is “Mu’s voice,” as Iona guesses from reading the first paragraph. Perhaps translating is another kind of storytelling: finding the writer’s voice, unravelling the narrator. Yet Iona’s storytelling is frustrated by the muddle in this new job—she still feels she knows so little about where their story started, how it ended here, where they are now.

It is a long letter. The dusk is falling quietly at Iona’s window. She

reads on until she reaches the end of the letter and goes back to the beginning again. Slowly she types out the text, consulting her dictionaries when an unfamiliar word crops up.

Kublai Jian

Dover Immigration Removal Centre

Dover 2ER 4GS

UK

20 January 2012

Dear Jian

,

A letter at last! Finally I now know where you are! I’ve been so worried. I’ve been ringing Amnesty in London and every other refugee agency I can think of, but they didn’t know anything about you. And only one small postcard with the words “I am safe” isn’t enough. Tell me more. I am still in shock about your disappearance. It’s been over a month now, our home is bare without you, and I feel exhausted and angry. Please. Just tell me what’s going on. How can politics really be worth all this?

There’s so much I want to tell you. Without you, my sense of stability disappears

.

Right now I cannot even begin to countenance your ideas about art and politics. Even if you are right in what you believe in and what you fight for, argument and revolution seem so unimportant right now. All I can do is separate you from your manifesto and think about what it was like before all this

.

I hope this letter reaches you. I am sitting in a corridor in the People’s Liberation Army Hospital in Shanghai. My father has been diagnosed with terminal throat cancer. And all I can think is: why aren’t you here with me?

This feels like a place for the nearly dead. There are people here for all kinds of radiation treatment

—

cancer, leukaemia, diabetes, kidney diseases. But most are terminal cancer patients like my father. My father, Jian. You know. My father! I have one, even though you like to pretend we have no families and you have no father at all

.

The last two lines are entirely cryptic for Iona. Why would he pretend he has no family? She reads on.

I wish you were here with me in this strange antiseptic place. I wouldn’t have to explain it, I wouldn’t have to describe it. But I want you to know, Jian, what my reality is right now. Even if I can’t know yours. It’s the closest we can get to being in the same room. This is what’s going on, bear it if you can. My father is being transferred to the intensive care ward at the back of the hospital—each room has six patients alongside their relatives on camp beds. There is nothing to do here but wait: we lie on our beds, hot in the sordid air. The wives tend to their husbands, feeding them, watching them. The windows are closed, the fans turned off. They don’t want anyone to catch cold so the air is thick with heat despite the cold outside and the frost making patterns on the windows. My mother is sitting beside my father, watching the vitamin drip connected to his vein, feeling the pulse on his wrist. A big sign

—

SILENCE—is on the wall. Silence is all we have. No one reads books or listens to the radio. Sometimes one of the relatives, an uncle, mother or sister, falls asleep during the night on the camp bed by the side of each hospital bed, their head leaning over against the patient’s feet, body stiff from being in the same position for so long. This endurance leaves us stiff and numb—unable to think or feel much further than the aches in our own bodies

.

After midnight the nurses stop coming. A cleaner will come to distribute hot-water bottles and clean up everyone’s discharges. The toilet is located at the end of the passageway, but none of us use it. It looks like hell—God knows what’s floating on the floor, from dead or near-dead people. This is a corridor of death

—

you would not want to be here

.

My corridor is lined with late-stage patients waiting to enter the radiation room, wrapped in striped uniforms ready for this advanced Western machine to kill the evil cells in their bodies

.

My father meditates while he waits. He looks calmer than the rest of us. He says it’s the only way he can endure the wait. My mother is sitting next to me, staring at the letter I am writing to you. And what a good thing she is illiterate! Otherwise I would never cope with her! And you know what she says, Jian? “I only have one regret in my life, I wish I had learned to read and write.” Then she sighs. And it makes me think of you and me. What has all our reading and writing given us?

A shrieking siren is flying down a nearby road and wakes Iona from her focus. A high-pitched voice is speaking through a megaphone, and now a group of voices follow rhythmically. There is a protest going on somewhere close by, Iona realises. As she listens more carefully, she can almost make out the sound of anti-capitalism protest slogans. She stands up, closes the window. She can’t quite face the relentless bad news that’s sweeping round Britain; her ears have grown weary of it.

I’ve been making an effort to talk to my father, ever since I came here. It scares me, but I don’t know when there will be another chance. I talk to him about anything and everything, especially his past. And he answers me in writing, since he can no longer speak because of the throat operation he’s had

.

So I asked him, “Father, what do you believe in?” Silly question, I told myself. My father is a crazy man, nearly as crazy as you! But he has a pure, uncorrupted nature; he has dedicated his whole life to the party and he believes in it all

.

So my father answers me, and I can feel his anger as he writes, “Oh, Mu, you should know by now!”

“So tell me again,” I say, calmer, as if I’ve never met this old man. My father puts down his pen and stares at me in disapproval. “Even now, do you still really believe in communism?”

He picks up his pen and writes each word on his notepad with intensity, pressing the biro into the page with deliberate force. “Like everything, communism has its faults, but it’s our only hope.”

I can feel his unwavering strength even as he lies sick and weak. He uses such force to write these words that the sharp tip of the pen rips through the paper

.

You know, you and my father are made of similar stuff. I know it seems mad, but in his case he believes in communism; and you, you believe in freedom of expression through confrontation, even if it involves confronting the state and your own father. Years of life separate the two of you, but what I want to say is this: my father wanted to be a free person but rigid Communist ideology has been killing him little by little over the years. I think that’s why he has this cancer. He has been fighting like mad throughout his life, but the disease is swallowing him, he cannot win. You are still young, Jian. Is it worth it? Think about it

.

Your Mu

9

LONDON, MAY 2013

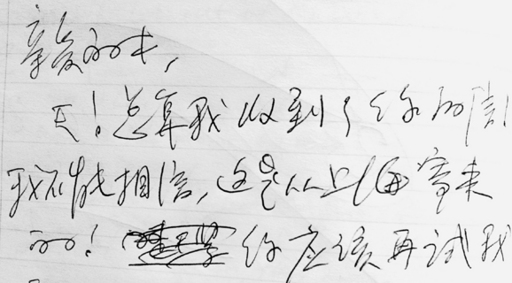

It’s early afternoon. Iona has retreated to her bathroom and to a warm bath. Reclining in the steamy water, she reads a letter. Often when a certain frustration colours her mind, slipping into a hot bath seems the only way forward. There’s a delicate, musical drip from the tap, and the paint is peeling away from the ceiling in orange-peel curls. The flat needs serious work but her landlord is dismissive at best. The page she is holding with one dry hand is covered with doodles, black ink mixed with blue. Large characters. She recognises Kublai Jian’s scrawl. Here and there the words have been furiously crossed out.

It’s a difficult text. Iona strains to understand. Jian seems very angry, and she doesn’t totally comprehend some of the idiom he uses. She feels stressed. The Chinese seem to love using old, formal idiom, even when a young person is writing. But there is also masses of text written in a very colloquial way, as if it were a blog or an email dashed off

in a rush. Nightmare if you’re trying to produce some sort of stylistic coherence in the translation! Modern Chinese colloquial idiom is the worst, she thinks. Her dictionaries are no help in deciphering many of Jian’s expressions. There are so many basic difficulties in translating Chinese into English, Iona thinks. No tense differentiation; no conjugation of verbs; no articles, no inversion in questions—and I have to invent all this and add it to fit the translation. She gets out of the bath, the water having lost its reviving quality, puts on her dressing gown and wraps her hair in a towel.