i bc27f85be50b71b1 (254 page)

Read i bc27f85be50b71b1 Online

Authors: Unknown

AI'PI NJ)[X III-A: \H[)[C\[ -SURL[CA[ FQUIPMENT IN mE AClITE CARE'. SETnNG

809

.1. Kacmarek RM. Oxygen Therapy. In RM Kacmarek, CW Mack, S

Dimas (cds), The Essentials of Respiratory Care (3rd ed). St. Louis:

Mosh), 1 990;408.

4. Scanlan el, Heur A. Medical Gas Therapy. In DF Egan, CL Scanlan

(eds), Egan's Fundamentals of Respiratory Care (7th ed). St. Louis,

Mosby, 1 999;738,748.

5. Ryerson EF, Block AJ. Oxygen as a Drug' Clinical Properties, Benefits,

Modes and Hazards of Adminisrrarion. In GG Burron, JE Hodgkin

(cds), Respiratory Care, A Guide to Clinical Practice (3rd ed). Philadelphi., Lippincott, 1 99 1 ;325-326.

6. Kacmarek RM. Neurologic Control of Ventilation. In RM Kacmarek,

CW Mack, S Dimas (eds), The Essentials of Respiratory Care (3rd ed).

St. LoUIS, Mosby, 1 990;80.

7. Dally FK, Schroeder JP. Clmical Management Based on Hemodynamic

Parameters. In FK Dady, JP Schroeder (cds), Techniques in Bedside

Hemodynamic Monironng (5rh cd). Sr. lOUIS: Mosby, 1994;235.

8. Whalen DA, Kelleher RM. Cardiovascular Parient Assessmenr. In MR

Kmney, SB Dunbar, JM Vitello-CiCClu, et al (eds), AACN's Clinical Reference for Crincal Care Nursing (4rh ed). Sr. louis: Mosby, 1 998j303.

9. Smith RN. Conceprs of Monitoring and Surveillance. In MR Kinney, S8

Dunbar, JM Vircllo-Cicciu, er 31 (cds), AACN's Clinical Reference for

Cntlcal Care Nurs11lg (4th ed). St. Louis: Mosby, 1 998;1 9.

10. Bridges Ej. tvloniroring pulmonary ,urery pressures: jusr rhe facts. erir

Care Nurse 2000;20,67.

I I . Daily EK, Schroeder JP. Principles and Hazards of MOnlroring Equipment. In EK Dally, JP Schroeder (cds), Techniques in Bedside Hemodynamic Moniroring (5th ed). St. louis: Mosby, 1 994;37.

12. Bridges El. \Voods SL. Pulmonary artery pressure measurement: state of

the art. Heart Lung 1 993;22,99.

13. Hickey jV. Theory and Management of Increased Intracranial Pressure.

In JV I

(cd), The Chnical Practice of Neurological and Neurosurgical NUr

1 4. Boss Bj. Nursing Management of Adults wirh Common Neurologic

I'rohlems. In PG Beare, JL Myers (eds), Adult Health Nursmg (3rd ed).

St. LouI" Mosby, 1 998;9 I 7-924.

III-B

Mechanical Ventilation

Sean M. Collins

Mechanical ventilatory support provides positive pressure to inAare

the lungs. Patients with acme illness, serious trauma, exacerbation of

chronic illness, or progression of chronic illness may require mechanical ventilation.1

The following are physiologic objectives of mechanical ventilation':

• Support or manipulate pulmonary gas exchange

• Increase lung volume

• Reduce or manipulate the work of breathing

The following are clinical objectives of mechanical ventilation':

• Reverse hypoxemia and acme respiratory acidosis

• Relieve respiratory distress

• Reverse ventilatory muscle fatigue

• Permit sedation, neuromuscular blockade, or both

811

812 AClITE CARE HANDBOOK FOR PHYSICAl THFRAI'ISTS

• Decrease systemic or myocardial oxygen consumption and

intracranial pressure

• Stabilize the chest wall

• Provide access to tracheal-bronchial tree for pulmonary hygiene

• Provide access for delivery of an anesthetic, analgesic, or sedative medication

The following are indications for mechanical ventilation2;

• Partial pressure of arterial oxygen of less than 50 mm Hg with

supplemental oxygen

•

Respiratory rate of more than 30 breaths per minute

•

Vital capacity less than 10 liters per minute

• Negative inspiratory force of less than 25 em H20

• Protection of airway from aspiration of gastric contents

• Reversal of respiratory muscle fatigue3

Process of Mechanical Ventilation

[lltubatioll

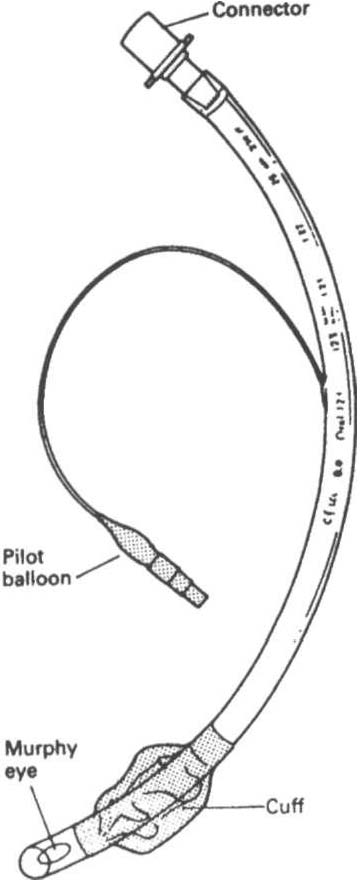

[lltubatioll is the passage of an artificial airway (tube) into the

patient'S trachea (Figure III-B. 1 ), generally through the mouth (elldotracheal tube intubation) or occasionally through the nose (Ilasotracheal intubation). Intubation is considered for four reasons: (1) the presence of upper airway obstruction, (2) inability to protect the

lower airways from aspiration, (3) inability to clear pulmonary secretions, and (4) the need for positive pressure ventilation.' The process of removing the artificial airway is called extllbatioll.

When patients require ventilatory suppOrt for a prolonged time

period, a tracheostomy is considered. According to one author, it is

best to allow 1 week of endotracheal intubation; then, if extubation

seems unlikely during the next week, tracheostomy should be considered.1 However, a patient can a)so be intubated for many weeks without tracheostomy, depending on the clinical situation. A trache-

,\PPENDIX III-B: MECHANICAL VENTILATION

813

Figure ill-B. I. A typical endotracheal tube.

ostomy tube is inserted directly into the anterior trachea below the

vocal cords, generally performed in the operating room. Benefits of

tracheostomy include (I) reduced laryngeal injury, (2) improved oral

comfort, (3) decreased airflow resistance, (4) increased effectiveness

of airway care, and (5) feasibility of oral feeding and vocalization.· If

the patient is able to be weaned from ventilatory support, humidified

oxygen can be delivered through a tracheostomy mask (Table IU-A.l).