Iced!: The 2007 Journal of Nick Fitzmorgan (8 page)

Read Iced!: The 2007 Journal of Nick Fitzmorgan Online

Authors: Bill Doyle

THE LUKLA AIRSTRIP IS REALLY SHORT!

I squinted and finally spotted a sliver of pavement perched precariously on the side of a mountain. A tiny village, which

must be Lukla, butted up against the strip.

I think someone forgot to tell whoever built the strip that planes, not gnats, were going to land here.

As we descended, I could see a group of villagers gathered halfway up the mountain. They were pointing at us, clearly watching

our approach—almost as if they expected us to crash.

Looking back at the impossibly small airstrip, I expected the same thing.

“This is crazy!” I shouted.

But Maura remained calm. The comers of her mouth twitched. “I bet those bloodsucking leeches are sounding pretty good right

now,” she said, the closest thing to a joke I’d ever heard her say.

I couldn’t laugh. The nightmare I’d had earlier was nothing compared to the terror of this!

The plane went almost completely vertical for a moment, and I was looking straight down. Swirling air created by the nearby

mountains slammed into us. My head bumped up against the ceiling. I pulled the strap of my seat belt more tightly around me

and held on.

Maura leveled out the plane at the last second. I was impressed not only with myself for keeping my eyes open the entire time,

but also with Maura for the way she managed to bring the plane down safely and relatively smoothly.

“Wow,” was all I could manage to say as the plane came to a halt near a small building that I guess served as the terminal.

We unbuckled our seat belts and climbed out of the plane. Maura looked as relaxed as if she made this kind of landing every

day, but my feet had never been happier to be on solid ground. The air was crisp and pure and was a pleasant 60 decrees or

so. At this altitude, I knew the oxygen levels in the air would be much lower than I was used to.

Some people can develop altitude sickness or hypoxia. This sickness can get really bad. In fact, it can lead to hallucinations

and messed-up decisions. Thanks to the last three weeks of training in the mountains around PDA, I thought I had a head start

on getting acclimated, or used to, the higher altitudes.

Maura said we should wait by the plane. A tall, dark-haired man wearing a gray business suit was already walking across the

tarmac toward us. Two armed soldiers strode behind him.

“That must be the government official. Give me your passport and let me handle this,” Maura said quietly to me.

OUR GREETERS AT THE AIRSRIP

“No problem,” I replied, happy to avoid dealing with the gun-toting soldiers. “I’ll get our bags and wait for you over by

the terminal.”

I grabbed our two backpacks and made my way over to the small building. My head had started buzzing, and I felt the twinges

of nausea in my gut.

Telling myself to stop being such a baby, I watched as Maura shook hands with the dark-haired man. She handed him our passports.

I heard a few words, including Judge Pinkerton’s name. At the mention of her, the man smiled and the soldiers backed off slightly.

Obviously, even here, Judge’s name carries some weight.

Then the wind picked up, and I couldn’t hear anything else.

Luckily, I can read lips.

I saw the dark-haired man say the words: “A private plane landed here yesterday.”

Maura glanced over at me quickly and then turned away. She indicated that the man should do so as well. They both had their

backs to me, and I couldn’t hear or see any more of their conversation.

After a moment, Maura and the man shook hands. I saw her tell him that we would be back for the plane within a week. The man

smiled, and I could see him say, “No problem. No problem.”

The man told the soldiers they could go, and Maura led the man over toward me. He asked if I was bringing any food or dangerous

substances into the village. When I answered no, he handed our passports back to us and told us to have a nice day.

I saw him give Maura a look. A silent communication seemed to pass between them.

Or was I just imagining things?

My head was really starting to pound now. Maura and I slung our packs over our shoulders and headed through the terminal.

I was bursting with questions. Had the official seen my dad? Had he been on the plane that landed yesterday? But Maura held

a finger to her lips and said, “Let’s wait to talk.”

We made our way into the village, which cascaded down the side of the mountain at seemingly impossible angles. The hard-packed

dirt road twisted and turned through the various one-story buildings. The window frames and doorframes of the wood houses,

inns, and businesses were painted in cobalt blue or other bright colors. Villagers bustled about, some carrying goods to trade,

others shopping. There were women with bright purple and red shawls wrapped loosely around their heads and some of the men

wore “dokos,” a kind of backpack. The tourists were easy to spot—because of the way they were dressed and the cameras most

of them had slung around their necks.

LUKLA VILLAGERS

But the buzzing in my head was growing louder. And I was having a tough time concentrating on anything, let alone the pleasant

postcard setting.

“you have to tell me,” I demanded impatiently. “Did you ask that man if he’d seen my dad?”

Maura stopped walking, seeming surprised by my urgency. “The official told me that no other private planes have landed here

in the last day.”

“What?” I stammered. That isn’t what he had said … or maybe I had misread his lips. “Are you sure?”

“I was standing right next to him. So, yes, I’m sure.”

The involuntary twitch of the corners of her eyes and the quick jerking movement in her shoulders told me all I needed to

know.

She was lying!

I was too stunned to speak. Had my dream been an accurate warning after all? Had I just flown to a distant country with someone

whom it was dangerous to trust? But why would Judge have sent Maura to help me if she wasn’t trustworthy? Had Maura actually

managed to fool her?

If only my head would stop ringing, maybe I could piece it all together. But I couldn’t seem to catch my breath. …

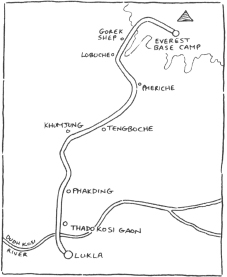

“Can I see your guidebook?” Maura asked, apparently oblivious to my inner doubts. Without a word, I handed her the book. She

flipped to the map and studied it for a second. Then she looked at me. “You seem tired. Should we bunk here in the village

tonight?”

“No,” I said absently. “Our plan is to catch up to my dad before he reaches Mount Everest. And we won’t do that if we go to

sleep.”

“Okay. You’re right. There’s still plenty of daylight. I think we can make our way to Phakding. We’ll be that much closer

to Everest the next day.”

Maura and I headed west, and the road took us out of the village and soon became a wide dirt path, which dropped steeply.

Then the trail turned north and descended once again to a village called Thado Kosi Gaon. We hiked through an enormous green

field. I was surprised by all the tall grass and yellow wildflowers. I always Imagined the area around Everest would be rocky

and snow-covered.

My head now felt like it had been stuffed with a pillow full of angry bees. But I was able to come to a decision: I would

pretend that everything was fine between Maura and me until I had a chance to act.

We crossed over the Dudh Kosi river on a rickety wood bridge and twenty minutes later, we reached Phakding. The sun was going

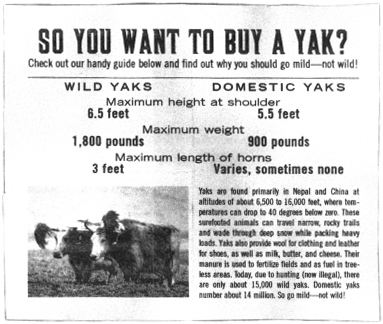

down as we entered the small village. Two men walked by, leading a large yak.

Now’s my chance, I thought.

I acted as if I’d stumbled on a loose rock on the road. I fell against the yak. It smelted horrible! With my hand hidden from

view, I quickly plucked several hairs out of the beast.

The yak was enormous—but apparently pretty sensitive. It let out a little grunt of pain. One of the men yelled something in

Nepali at me, but they kept walking.

“What just happened?” Maura asked.

“Nothing.” If Maura was going to keep secrets, than I decided I had better do so, as well. I tucked the yak hairs into my

pocket for safekeeping.

We continued on our way through the tiny village, which was really just a group of small houses and businesses. The blue-and

green-painted roofs reminded me of the wild-flowers we’d passed on our trek. Thankfully most of the signs in the village were

written in Nepali and English, so we could read the one for the Mountain Inn and Lodging. It was a two-story stone building,

which had been painted a dark pink.

Inside the tiny lobby of the inn, there were several groups of other Americans here for the night. Each group was being led

by one or two muscular men with smooth brown skin. These must be Sherpas, I thought.

ABOUT THE SHERPAS

The first Sherpas migrated from Tibet to Nepal about 500 years ago. Now there are roughly 10,000 Sherpas in Nepal, about 3,000 of them in the Khumbu valley. Their skills and physical strength at high altitudes are unmatched, and Sherpas are usually a vital part of any successful climbing expedition. Before climbing became such a major industry, most Sherpas were traders.

I walked up to several of the travelers and Sherpas. I showed them a photo of my dad I had taken last New Year’s Eve. His

short dark hair framed his good-looking face. And he was giving his trademark toothy grin.