Icelandic Magic (9 page)

AIMS OF GALDOR

Once the grammar of the galdor staves and galdor signs has been masteredâno easy feat, it must be admittedâthe practitioner is free to create his or her own signs to effect things magically. It will become like carrying on a conversation with the world order. As wisdom is gained it will be learned just what communications the world is open to and which ones it is not open to. Learn to speak to a receptive world. In general the Father of Magic is your friend and wants to help you in your endeavors. But more than anything he wants to teach you to be wise.

The aims of galdor-sign magic are virtually limitless, but the following list represents many of the more common uses, in no particular order.

- discovery

- strength

- safety

- luck

- influence over others

- safe journey

- acquisition of love/sex

- acquisition of money

- success in business

- wisdom

- guidance

- safe crossing of barriers

- gaining access to hidden knowledge

- finding one's way in unknown territory

- courage

- healing sickness

- opposing enemies

- identifying who has wronged you

INTERPRETATION AND CONSTRUCTION OF SIGNS

With galdor signs the magician can map and remap reality in conformity with the will. The most powerful act of magic and the greatest form of “prayer” is that which is given geometrical reality (as a unique stave) in harmony with a verbal message (the corresponding spell) and hidden in the realm of the secret willâdeep and inaccessible to the conscious mindâbut inexorably linked to the realm out of which events emerge.

It can be said that there are three distinct types of magical figures used in the kind of Icelandic magic contained in black books of the kind you now possess. These are:

- ægishjálmar

(helms of awe) - galdramyndir

(magical signs) - galdrastafir

(magical staves)

The latter two are usually not distinguished in later times, although the terminology itself appears to indicate that the

galdramyndir

were originally more free-form, whereas the

galdrastafir

were generated from runes, magical letters (

galdraletur

), and especially from bindrunes (

bandrúnar

). To understand the runes and the much less well-known tradition of “magical letters” found in historical manuals of magic in Iceland, we have included lists of them in appendices A and C.

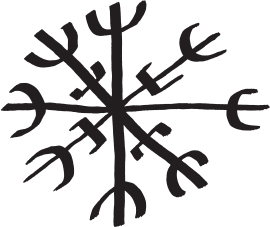

ÃGISHJÃLMAR

The simplest magical sign in Icelandic magic is the basic

ægishjálmur,

or “helm of awe.”

Fig. 9.2. Simple ægishjálmur

The name of this figure has been associated with the “serpent power” present in the body of humans, which is mythically linked to the dragon or serpent Fáfnir, slain by the great hero Sigurd. This myth is recounted in the

Eddas

as well as in the

Völsunga Saga.

Historical magical books such as the

Galdrabók

show that the sign is closely associated with the area of the forehead between the eyes of a human being.

The fact that this figure is called a “helm”âmore literally, a “covering”âindicates that in fact its power is intended to overlay or subsume the reality over which it is cast by the will and design of the magician. This is done at two different levels: subjectively or objectively. When used subjectively, this means that the power is cast over the magician in workings of self-transformation. Here we are reminded that the man or giant Fáfnir actually

transformed

himself into a serpent with the ægishjálmur's power. When extended objectively, this means that the power is cast over the world or environment surrounding the magician in workings of sorcery. What makes the helm of awe an especially powerful “map of magic” is that it connects the subjective and objective universes in a synthetic way, which gives the inner will of the magician a high level of influence over the objective universe, because both realms are clearly seen as parts of the same whole.

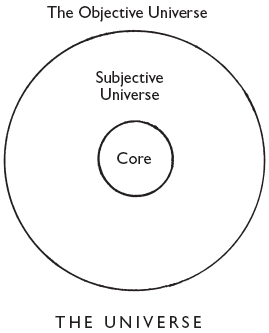

The entire visible plane, or two-dimensional field, onto which the

helm of awe is drawn or cast represents the whole universe. Within this

greater plane there is a circular zone that represents the subjective universe

of the magician: his soul and mind, and their contents. At the very core

of the circle is the self of the magician, the source of the magical casting

itself. Alternatively, the core can be made to represent the object, or aim,

of the magic. This can be “mapped” in the manner shown in figure 9.3.

Fig. 9.3. Zones of mapping for some magical signs

The zones of the

ægishjálmur

can be further refined, but we will

leave this up to more empirical results of magical experimentation

within the tradition. It is hoped that a community of students and

teachers of this kind of magic will develop in the years to come.

In casting a helm of awe the magician is to imagine the arms of

the sign as currents of force emitting from the core of his being and

flowing both outwardly and inwardlyâbeing projected forcefully,

remaining steady, being received forcefully or being blocked, redirected,

or circulated as the sign determines. Again, the key is that the sign is

not two-dimensional

,

but it exists on

at least four dimensions

. Begin by

seeing and feeling the sign as a three-dimensional figureâas existing in a sphere. The three-dimensional model of Yggdrasill, the Germanic world tree that vertically and horizontally encompasses the many worlds of the universe, is a good conceptual place to start. The typical eight-armed

ægishjálmur

is really a reference to the four cardinal directions and the four vertical worlds along an axis both above and below the subject as conceived of anywhere in space. The two inner worlds on the vertical axis are above and below the subject, but the outer two on the vertical pole are actually in another dimension of time and space: these correspond to the realm from which events originate and the realm where transformations are made.

Obviously the number of arms on a helm gives an indication of the way in which magical space is being modeled: typically the helms have eight, six, or four arms. Eight arms refer to the eight divisions of the sky and earth (the

ættir

); six arms refer to the four cardinal points and a vertical axis; while four arms refer to the cardinal points of the mundane universe. However, many more configurations are possible.

According to the zone-mapping model shown in figure 9.3 above, the closer a symbol is to the center of the map, the closer it is to the middle of the subjective universe: either that of the magician or, alternatively, that of the object of his or her operation. In the multidimensional philosophy implied by galdor-sign magic, these are often

temporarily

seen as being one and the same. The farther out from the center that a symbol or feature is on the sign, the more it is reaching into the objective universe around the subject.

An example of a more complex helm of awe appears in figure 9.4. This shows a sign with a strong fortress of protection around the middle of the subjective center while insulating the inner and outer worlds from one another and projecting a fierce stance toward the outer world, which says that the subject casting the helm should be approached only with trepidation. This is a typical message sent by many helms of awe.

When charging or vivifying a helm of awe in a magical working, magicians are to visualize themselves at the center of the figure, their souls configured by the geometry of the inner part of the sign while their wills are powerfully projected out through the arms of the sign. The power is modified, modulated, and shaped according to the nature of the terminal figures. These can either thrust outward into the universe surrounding the magician or, alternatively, put up shields around the magician. Experiment empirically with the specific shapes of the symbols and use what feels right for you at the time. Being overly prescriptive in a dogmatic way about these matters leads to diminished effectiveness.

Fig. 9.4. A helm of awe

GALDRAMYNDIR

The magical signs or images called

galdramyndir

are those that have their origins in abstract or hidden keys other than runes. Technically speaking, the term

galdrastafur

(“magical stave”) can be reserved for those signs that have their origins in rune-stave shapes (see fig. 9.5

below).

One glance at a book of Icelandic magic will give the viewer the impression of many wild and entirely unintelligible signs. To some extent these signs can be interpreted, but it is only to a limited extent because fundamental to their construction and execution is the idea that there is a synthesis of rule-bound regularity or predictability and a subjective, creative whimsy. This latter element is important to the idea of hiding the meaning of the signâeven from the conscious mind of the one who created it!

Icelandic magical signs are represented in the realm of two dimensions, most often on a flat piece of paper or parchment or carved on a flat piece of wood. However, the signs are in fact multidimensional. The key to charging them is to see them in multidimensions. Using your spatial imagination, make them “pop” off the page. When this happens, you have made contact with the spirit of the sign.

Other extra-dimensional aspects of signs include the alchemy of the senses: signs can appear as

visual

graphic models in space, but they can be endowed with qualities of

sound

as well.

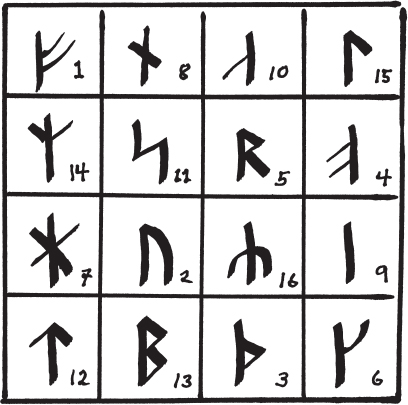

As we saw in chapter 5, one of the elements of the southern Mediterranean tradition that found a quick and easy home in the North was the use of so-called magical squares. The famous

sator

-square is found in several runic inscriptions from all over Scandinavia in the Middle Ages. It is utilized in a very practical way. In line with this, it seems logical that a numerical/runic square of sixteen segments would also find a useful place in the practice of Icelandic galdor-sign magic.

Fig. 9.5. A sixteenfold magical square with numbers and runes

This particular square is used as a powerful tool both to analyze certain preexisting signs found in the traditional record and to create meaningful new signs of your own. One of the important esoteric principles for working galdor-sign magic is that of

hiding

the obvious meaning of a sign by the use of such tools. By hiding the meaning (even from the conscious mind of the operator) the magical effects can work more freely and quickly in the worlds beyond Midgardâbeyond the realm of the five senses and three dimensions that constantly feed this world with events.

We can create an apparently abstract magical sign by connecting the runes that make up a name (of Ãðinn, for example) or a concept (translated into Old Norse) in such a way that a geometrical figure emerges, which, in reality, is a “magical runic signature” of the word in question.

The first step in creating a magical sign based on an Old Norse name or word is to transliterate the word into runes. By way of example, we will transliterate the Odinic nickname Sig-Týr (Victory God) into runes following the rules given in appendix A. Doing this, we come up with .

.

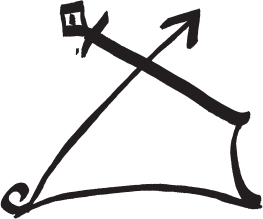

Now we take the sixteen-rune grid and trace the name through the runes and come up with the shape shown in figure 9.6. This shape is then further stylized and provided with flourishes for magico-esthetic reasons. The final shape is shown in figure 9.7.

Fig. 9.6. The raw signature of

Fig. 9.7. The finished signature of