If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home (37 page)

Read If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #History, #Europe

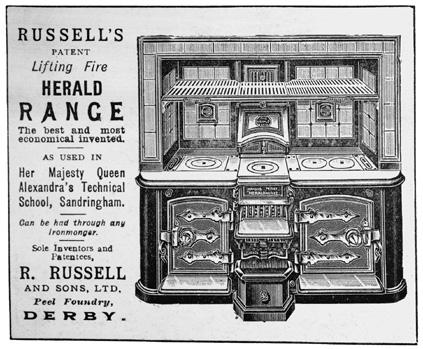

The arrival of the kitchen range revolutionised cooking, slashed fuel consumption, standardised recipes and encouraged the use of the saucepan

Like the expensive and finely tuned instrument that it was, the range needed careful cleaning and maintenance. It required ‘blacking’ twice a week, first thing in the morning, a process that took about ninety minutes. The ‘black lead’ polish was brushed into the iron surfaces, then buffed up to a shine. A recipe for this noxious polish, given in

The Footman’s Directory

(1825), requires ‘two quarts of small beer, eight ounces of ivory black, three ounces of treacle, one ounce of sugar candy, half an ounce

of gum Arabic’, plus ‘oil of vitriol’. I know from my own experience of blacking the range at Shugborough Hall that it takes a week for traces of the polish to work its way out from underneath the fingernails.

With the range, more efficient kitchen design was now on its way. But progress came in fits and starts: the range represented a significant financial investment, and there was still an emotional attachment to the welcoming, leaping flames of the wide hearth. ‘Would our Revolutionary fathers have gone barefooted and bleeding over snows to defend air-tight stoves and cooking-ranges?’ asked Harriet Beecher Stowe during the American Civil War. Indeed no, she said: the ‘great open kitchen fire’ was their motivation; the memory of it kept ‘up their courage’ and ‘made their hearts warm and bright with a thousand reflected memories’. Indeed, even in the 1930s America’s president would call his radio broadcasts his ‘Fireside Chats’.

And conservatism ensured that kitchens remained places of standing, scrubbing and stirring, with only rare glimpses of comfort. The Victorian household expert Mrs Panton recommended that kitchen servants might possibly be allowed to lay ‘a rug, or good square of carpet’ down on the floor, but only after their work was done and if they were very careful with it. Likewise the architect J. C. Loudon suggested in a mealy-mouthed manner that ‘a small looking glass might promote tidiness of person and a piece of common carpet would add to the comfort of the room’.

But the seemingly endless labour of feeding, firing, cosseting and cleaning the range would not last for ever. Gas cookers – marketed as ‘wageless servants’ – were among the items displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851, and by 1898 one in four homes had both a gas supply and a cooker. Many people hired their cookers from their local gas company, rather than buying them outright.

In 1923, an extraordinary invention appeared: the ‘Regulo’.

This was a thermostat for a gas oven, so that for the first time meals could be cooked at a known temperature over a measured length of time. This turned cooking from an art into a science. Adverts trumpeted the Regulo as an ‘inestimable boon to our wives and daughters, enabling them to prepare for us, with the minimum of attention, a repast cooked with automatic precision’.

The electric Belling ‘Modernette’ cooker of 1919. The gas and electricity companies waged all-out war for customers

While gas had the advantage of cheapness, electricity would challenge it as Britain’s favourite kitchen fuel in the late nineteenth century. The great drawback to early electrical supplies was the wild variation between the voltages produced by different plants in different towns. This meant that no electrical appliance could be made and sold nationally. This eventually began to change in 1926 with the laying of plans to create the National Grid, and in 1930 a group of manufacturers finally managed to agree a set of common standards for cookers. The electricity companies vigorously proclaimed the benefits of electric as opposed to gas cookers: they were easy to use, safer and cleaner. Even so, in 1939 a mere 8 per cent of British homes had electric cookers, and 75 per cent stuck with gas.

In 1908, Ellen Richards calculated that an eight-room house required eighteen hours of cleaning time a week just to remove dust. Washing the windows and walls would take the total up to twenty-seven hours a week, even before the clothes-washing, bed-making and cooking began. This was simply unsustainable after the two world wars removed the huge infrastructure of servants who had done such work in the past. Now there began to be a real necessity for efficient, labour-saving kitchens. Books for the newly servantless middle classes began to appear, with tactful titles such as

Cook’s Away. A Collection of Simple Rules, Helpful Facts, and Choice Recipes Designed to Make Cooking Easy

(1943). This particular volume teaches novices how to break an egg, and advises them not to chop onions with raw hands because the smell will linger and spoil the enjoyment of a later cigarette.

‘There cannot have been any time in the history of our country’, wrote Lady Beveridge in 1945, ‘at which the attention of all people has been so much engaged by the problem of housekeeping without tears.’ She rightly explained that ‘it is not only that so many houses have been destroyed’ by war, ‘but also that the remainder have been discovered to be all too frequently designed for a social system which is a thing of the past’.

After the Industrial Revolution, kitchen design became a matter for scientific study. This multipurpose cabinet represents a step along the way to the fully fitted kitchen

The history of post-war housing leads us towards prefabrication, standardisation and an ever greater squeeze upon space as Britain filled up with people. The fitted kitchen was in fact a German invention, first appearing in 1926 in a Frankfurt social housing project. Ten thousand of these so-called ‘Frankfurt Kitchens’ were installed. They were inspired by the narrow galley kitchens of railway trains, and the space they contained was tight but very well-planned. Shockingly modern to contemporary eyes, they had work surfaces which pulled out like drawers and draining boards on hinges which could be folded away. In them the housewife was conceived as an engineer, quickly and efficiently turning out meals; in fact, the design was partly intended to free up time which could be spent instead in Germany’s factories. But the design’s drawback also lay in its tiny size. Women

ended up working in there all alone, unable to keep an eye upon their children or to be helped by the rest of the family.

The Frankfurt Kitchen might have become more popular in Britain if it had not been for the Second World War. After the war, Britons tended to look west not east, seeking inspiration for new kitchen designs from their American allies. The large, luxurious fridges and kitchen units of a more spacious and less war-torn country became post-war desirables in Britain.

One of the early home-grown British fitted kitchen designs was ‘The English Rose’ of 1948, intended to use up the industrial-strength aluminium which had been stockpiled for building Spitfires. You could quickly fit out an entire kitchen by choosing various units and cupboards from the standard range. The work surfaces were covered with the new melamine, which could be wiped rather than scrubbed clean. It was quite an upmarket product, though, and if you couldn’t afford it, there were colourful sticky-backed plastics like Fablon or Stix-On to brighten up shelves or tabletops instead.

The extractor fan was perhaps the greatest mechanical development of the twentieth century, as it allowed kitchens and living areas to become one single space. The most recent transformation, though, has been the arrival of online services allowing you to order any food, raw or cooked, from anywhere, and to have it brought to your door.

A very cheeky 1970s billboard for Kentucky Fried Chicken read simply ‘Women’s Liberation’, and the production of food has now been transferred from the domestic to the public realm. What the Tudors used to call ‘dressing victuals’ is now broken down between extremely specialist producers all over the world. With many people today using their ovens as extra cupboards and their microwaves instead of their hobs, looking at the history of the kitchen is like surveying a lost realm which holds less and less meaning for us.

But perhaps with global financial chaos this is beginning to

change. Only a couple of years ago it seemed that ‘foodies’ were the few people who still cared about their kitchens. Apartments in New York were being built without kitchens at all, for people who order in every meal. Yet a slight movement in the direction of back-to-basics is apparent in dining habits, partly as a result of the efforts of the chef turned public-health expert Jamie Oliver. In 2003, only 24 per cent of Britons said that they ‘always cooked from scratch’, but today this has risen to 41 per cent.

Perhaps our recent recession has driven people to examine more carefully what they eat, and put a bit of life back into their kitchens. Now that cooking is no longer a matter of stirring, scrubbing and breaking your back, there is a dignity, beauty and generosity in putting time and effort into making something to eat.

38 – Cool

To ice CREAM. Take Tin Ice-Pots, fill them with any Sort of Cream you like, either plain or sweeten’d … you must have a Pail, and lay some Straw at the Bottom; then lay in your Ice, and put in amongst it a Pound of Bay-Salt; set in your Pots of Cream, and lay Ice and Salt between every pot … set it in a Cellar where no Sun or Light comes.

Mrs Mary Eales’s Receipts

, 1718

There’s no question that kitchens smelled bad in the past. Before refrigeration, seasonal food was not a desirable, it was a necessity. Even hours counted: one Victorian housewife insisted upon ‘an early dinner today’ because the salmon, green-pea soup, chickens and jellies she had ordered were going off in the hot weather. All cooks knew that putting charcoal in with tainted meat would absorb something of the putrid smell, and horseradish grated into milk would help it limp on for another few hours without turning.

How on earth, it’s tempting to wonder, did people store fresh food before the days of refrigerators? Actually, a stone larder is an astoundingly simple yet effective invention. A thick marble slab remains cold on a hot day, and fish and meat would be laid directly upon it. Then there was the ice house, a wonderful invention, first heard of at St James’s Palace in 1666. Called

the ‘snow-well’, this one was sunk into the ground and given a roof of straw. It was most convenient to build your ice house near your lake, if you had one, so that in winter it was easy to carry in frozen lake-water and pack it in straw for the summer season. In a dark, underground room of a constant temperature, ice could last nearly the whole year.