If You Only Knew (12 page)

Authors: Rachel Vail

“But,” I echoed. “CJ’s my best friend, and she said she liked him first. I mean, we’re getting friendship rings tomorrow. CJ and I. So how could I turn around and . . .”

“Where?”

“The rings?”

“Yeah.” Devin balanced one foot on top of the other and waited.

“Sundries.”

“Oh, I saw those,” Devin said. “You like them?”

“You don’t?”

She shrugged.

“It’ll just be good to have something of my own, for once.”

“But won’t CJ have the exact same ring?” Devin asked.

“Yeah, but . . . Never mind.” Here I was thinking Devin of all people was understanding me so well. The one who tortures me most. I should learn already not to trust her.

“Trust me,” Devin said. “You’ll be sorry if you buy them. One person will lose her ring or stop wearing it or something. It happens every time. Honestly. You buy friendship rings, you’re just asking for fights and trouble. Somebody ends up crying, and you know what, Zoe? It’s gonna be you.”

“What are you, a psychic?” I flopped down on my bed to face the wall and trace Tommy’s name into the paint with my finger some more.

I heard Devin turn on her lighted mirror. Why do I tell her anything? I should just keep everything inside, not let anybody except CJ know the real me. I can tell CJ anything. She doesn’t torture me with it, she doesn’t lecture me and treat me like a baby. Her friendship is the most important part of my life. It’s worth whatever it costs me.

The only thing I can’t tell her about is Tommy. Who am I supposed to hit with? And tease? And beat at bowling? And, OK, I admit it—flirt with? I can tell CJ anything but that.

Devin switched off her electric mirror and left. I pulled my blankets over my head and stayed in bed. When Mom noticed me in there, I said I had a headache and needed to sleep.

“Oh, not you, too,” she said.

“Why? Who else has a headache?”

Mom shook her head. “It’s the beginning of seventh grade. I’ve seen this four times already.”

I didn’t move while Mom pulled my shades. “I can’t even have a fake headache all to myself?” I asked her.

“Rest up,” Mom said on her way out. “It’s only September.”

I stayed in bed all day, listening to the

thunk-thunk-thunk

of Tommy hitting a tennis ball against his garage door.

twenty

O

ur breath made little clouds

on the display case in Sundries. Mrs. Dodge waddled over and asked, “Yes?”

In a confident voice, CJ said, “We’d like to see those rings, those two, please.”

Mrs. Dodge touched the green and gold shiny one. CJ and I shook our heads. She touched the silver matte-finish one with the big fake diamond hanging off, and we shook our heads again. Finally she touched one of the silver rings with the knot in the middle, plain but beautiful no matter what Devin thinks.

CJ and I nodded, together.

Mrs. Dodge took her gnarled finger off the ring and closed the display door.

“We want them,” CJ protested.

“Wait a while,” Mrs. Dodge said. She reached under the counter and slid open what sounded like a cardboard door.

“We’re ready today,” I explained. “Really.”

Mrs. Dodge shook her head and said, “I heard you. Relax.” She pulled out a plastic Baggie full of silver knotted friendship rings. Spilling maybe a dozen of them out on the black velvet rectangle, she said, “Find your size, girls.”

I spread them out and we looked. “So many,” I said. Not that I thought the two in the display case were the only rings like that in the whole world, but a Baggie-ful under the display—Olivia could come in anytime and buy one if she wanted, too, and Roxanne, even Gabriela. Even Morgan.

“Doesn’t matter,” whispered CJ. I felt like she had read my mind. She picked up one ring and slipped it onto her finger. It was so big it slid right off when she tipped her hand. I picked it up and tried to wiggle it on, but it barely got over my first knuckle.

I dumped it onto the rectangle and said, “Oh, well.”

“Oh, well,” she said back. We laughed and kept looking.

We found one to fit each of us. The ring was lighter than I had expected it to be.

This is it,

I thought.

Something of my own. This is what I’ve been wanting

. I smiled at CJ, but then had to look away. I’d expected to feel completely happy, I guess, and I couldn’t, not quite, not completely.

“This is what I’m putting in the paper bag,” I said, touching the ring with my thumb. “Myself in a sack.”

“Oh, I haven’t put anything in yet, have you?”

“No,” I lied. “Nothing yet.”

“I’ll put my ring in mine, too, OK?”

I shrugged. “Sure. I’d feel stupid if you don’t.”

“Great,” CJ said. “This, and a toe shoe, and what else? You could put in, maybe, a tennis ball.”

“I’m not that into tennis anymore,” I said. “I don’t just think about sports.”

“I know.” She twisted her ring around, admiring it. “Sorry. That’s not what I meant.”

“It’s OK.” I twisted my ring, too. This is what I wanted—to be chosen. Best friends. This friendship ring. Every time I get what I want lately, I burst into tears. To avoid that, I asked CJ, “How was ballet?”

She lifted her left leg and pulled it up with her hand, up over her head.

“Wow. Do you have any bones in there?”

She lowered her leg, smiling. “It was good, really good.”

“That’s great,” I told her, “that you’re feeling better about it.”

“I don’t know,” she whispered. Mrs. Dodge shrugged and turned away. “I can’t decide what to do and I’m not even sure if it’s my choice. I have to talk to you about it later. She knows my mother.”

“OK,” I whispered back. I wanted to be helpful to her. She seems so far away sometimes, with her own life I know nothing about. My best friend, I almost bragged to Mrs. Dodge. We’re best friends; we chose each other. “So. Did Tommy call you yesterday?”

“No,” she said. “I couldn’t stop thinking about him, all day. Well, except during dance class. But the whole way home, I was like, Tommy, Tommy, Tommy. You’re lucky; you’re so sane.”

“Yeah,” I said. “Good ol’ sane Zoe.” Sure. Like I spent the weekend thinking something other than Tommy, Tommy, Tommy.

“Seriously,” CJ protested. “It’s what everybody loves about you—you’re so . . . balanced.”

“Me?” I asked. I laid out my crumpled dollars for the down payment.

“You’ll have to come in each week with two dollars, at least,” Mrs. Dodge said, scooping up my money.

“No problem,” answered CJ, paying hers.

“No problem,” I agreed. “It’s worth it.” Did I need to convince Mrs. Dodge? Or who?

We each read the small type on an installment agreement. It felt so official and serious, like I should call a lawyer to look it over for me. Well, it is important; CJ had said so and I felt exactly the same. It’s a commitment.

I watched my new ring bob as I signed my name next to the X. Before I passed the contract back across the counter, I underlined the rounded letters of my signature.

There it is. That’s me,

I thought—just a little less pointy than the

Zoe Grandon

on Tommy’s note, the one thing I’d put into my brown paper bag so far. But of course I’d never bring it in like that. Myself in a sack is obviously much more than a boy who put a worm on my head in kindergarten likes me. Liked me. Whatever. Please.

I’ll take the note out when I get home,

I thought,

and find ten funny, reasonable things to replace it

. A piece of French toast might be funny, a fraying shoelace, my jam-packed phone book with everybody in my whole grade’s number and birthday filled in, this ring. Maybe I’ll keep the note for a little while, though. I’ll just hide it in the bottom of my sweatshirt drawer until I’m ready to throw it away.

Turn the page

to read the first part of

CJ’s story!

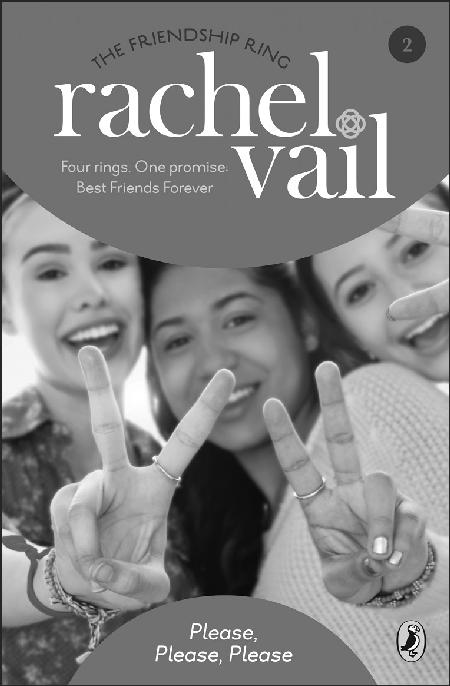

Please, Please, Please

one

M

y mother has a very complex

relationship with cows. Also with me. She grew up on a dairy farm, doing thick-booted chores in poop and milk drippings before dawn, fantasizing, while she mucked, of escaping to dance like a swan in the spotlight at Lincoln Center. Three days after her seventeenth birthday, instead of buying a dozen eggs and a jar of apple butter, she kept walking and used her grocery money plus what she’d hoarded over the years for a bus ticket. She never got onto the stage at Lincoln Center, but she did wait tables across the street for a few years, taking ballet classes and watching performances from the back with standing room tickets scraped from her tips. One night, the man standing beside her asked if she’d like a cup of coffee after. They got married, moved here, decorated the kitchen with a cow theme, and had me who might someday dance in the spotlight at Lincoln Center.

The only cows I know are pot holders and ceramic spoon handles. Milk comes from a carton, and I’m allergic to it. But every morning, my mother wakes me up before dawn to do my stretching, and although I don’t fantasize about standing in poop instead, my mind does wander.

My mother is very proud of me.

I’m just like her.

two

I

started ballet six years ago, and

from the first day of class, I was obsessed. Outside of the ballet studio, I was just a gawky, frizz-headed, stuttering first grader; once class started, the work was hard but clear—straighter, longer, higher, slower. Grace. Ballet made sense to me like nothing else in the muddled, rushed world. I just knew how to do it. My brother, Paul, was two and already talking, so smart and cute like he still is, like Mom, so different from me. Dance class meant no words for an hour, relief. I was nuts for it—I listened only to ballet music and practiced until my legs shook.

Ballerina

, I used to say to myself, falling asleep. Ballerina.

But now I’m in seventh grade—maybe my favorite musician shouldn’t be Tchaikovsky anymore. Maybe I should be eating cookies, even slouching occasionally, or crossing my legs (which I never do—it works against turn-out)—enough adagios, I think sometimes; I should be trudging with my friends though the mall on a Saturday, eating Gummi Bears, wearing a Boggs Bobcats soccer jersey with number five on the back. But then I lift myself up onto the tips of my toes and imagine waiting in the wings for my entrance. It’s hard to know which I want more.

I came up here to my room after dinner tonight to try to figure it out. I told Mom and Dad and Paul I couldn’t play catch with them because I had to work on my project for school tomorrow, but instead I’d stopped thinking and was just forcing my turn-out up on

pointe

, pressing the backs of my knees toward each other, listening to the beautiful

clock-clock

sound my brand-new toe shoes made

tap-tapping

against my wood floor.

My door opened and almost slammed me in the face. Mom.

“Ooo!” she said, at the same time as I said the same exact thing. “Phew,” she breathed, her hand up near her long, graceful neck, like whenever she’s nervous or startled. “So? How’s it going?”

“Good,” I said. “Fine.” I stood in fifth position flat on the floor. Mom smiled down toward my feet, at the toe shoes I wasn’t supposed to be trying on before getting my teacher’s OK. “I just, I . . .”

“I always did that, too,” Mom said. “How do they feel?”

“Perfect,” I said. We had just bought them a few hours earlier, and I couldn’t take my eyes off the cool pink satin.

She smiled. “Great. They look so beautiful.” She stood behind me, her fingertips gentle on my waist, and we looked at me in the mirror—my new pink leg warmers over pale pink tights, my new skinny-strap leotard, maroon, because now I’m in performance level. “I’m so proud of you,” Mom said. “Level Three.”

I balanced my head light on my shoulders, eyes steady and front. Not everyone gets invited up to Level Three.

“It really shows all the work you’ve been putting in is paying off.”

“Maybe,” I said, letting myself smile for a second. “I can’t do soccer, though.”

“I know,” Mom said. “That’ll be hard, huh?”

“Yeah,” I said, lowering myself down to flat feet. “Not, not that I’m any good at soccer, but . . .”

“But any time you go against the crowd, it’s hard,” Mom agreed.

“Mmm.” I rolled my head around to loosen up my neck.

“Well, when you get to be a Polichinelle this winter, and when your career blossoms like Darci Kistler’s did . . .”

“If,” I corrected, looking at the poster of Darci Kistler on my wall, daring to wonder for a second if I could ever have a career like hers. If I could, would it be worth giving up stomping around with my friends in the mud after school and taking the late bus home? Five dance classes a week is so much. Four days a week. It really means I can’t do anything else.

Mom kissed my hair. “I have every confidence in you.” She went over and sat down on my bed, her posture, as always, perfect but relaxed. I sat on the floor and pulled off my toe shoes, nestled them carefully inside each other, and slipped them into their white mesh bag. My mother looks like a young Jessica Lange—soft curls, soft features, soft eyes; casual but glamorous at the same time. I don’t look like any movie stars. I look like my dad—deep-set eyes and a little blotchy.