IGMS Issue 32 (9 page)

Authors: IGMS

The spirits truly gathered, summoned by the

mudang's

ceremony. Ori and the other ghosts turned away the mischievous ones, the too-intelligent ones. But the rest, he learned to accept. Even the ones that nestled against Jwi, sniffed her heels, clung to her hair. He learned that there were many aspects to the spirit world, not all of them malign.

After Ori had seen all four seasons at the temple and winter thawed into a reluctant spring, the mistress died. Her expression as she emerged into the spirit world was thoughtful. She bowed solemnly to her loved one and took his hand, as if she had always known that they would be reunited and life without him was a brief distraction.

Before they departed together for the kingdom of the dead, though, she told Ori, "She is a quick and adaptable learner, your betrothed. She asked me to thank you, when I saw you. So now I have."

In this way Ori learned that Jwi knew he was near, and thought of him still.

Jwi returned to her native village afterward. Although outcast once, it was not in her to hold it against them, and she was suddenly of inestimable value as a

mudang

.

Ori would have been content merely to watch her prosper and wait patiently for the day when they would meet -- properly, for the first time. But every morning, when the sun and the moon shared the sky, Jwi would wander into the bamboo grove to tap out a simple melody. And Ori tapped it back to her. Sometimes she would mouth a single, distinct word. At first he thought she said "

Oppa

," but then he realized that her lips did not compress into a "p", but widened into an "r". "Ori," she said, that silly childhood name of his that he would never now outgrow. No doubt she still went by Jwi, when she wasn't simply referred to as mistress

mudang

. Duck and Mouse, humble names intended to avoid the notice of the spirits and gods.

Jwi tapped on the bamboo, and so did Ori. And the spirits gathered around them, curious what this human and ghost were doing. Perhaps, inspired, one of them would try to pull a human through the veil, if only to play with until it got bored.

But Ori kept Jwi as safe as he could. Jwi whose heart was so in tune with the spirits, he had no doubt she would live as long as the

mudang

who taught her. Ori was not impatient. The day of her death would come, and then they would wed each other at last in the kingdom of the dead.

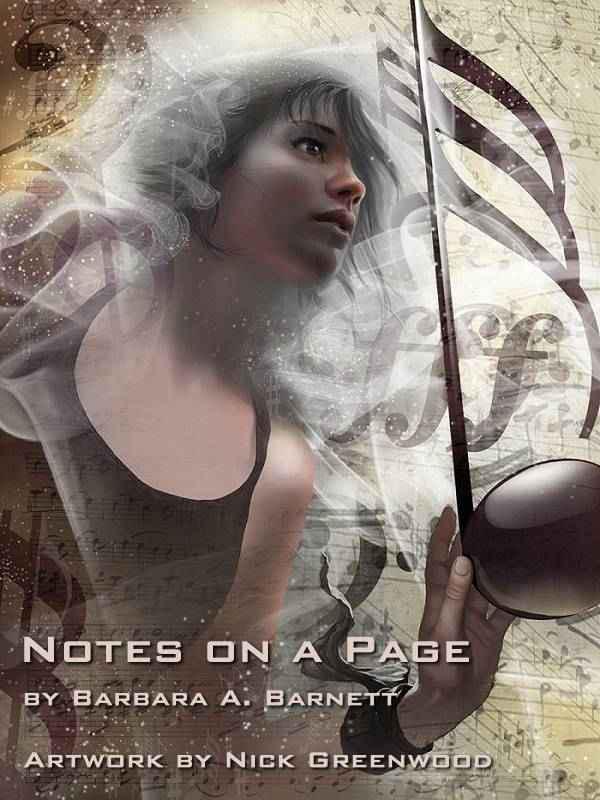

by Barbara A. Barnett

Artwork by Nick Greenwood

Yesterday Maestro Fuhrmann took the Beethoven so fast I was gasping for breath; today I'm wondering if I'll make it to the end of the phrase before turning blue in the face. Rehearsals like this leave me wishing I had learned violin instead of oboe -- string players aren't encumbered by the limits of their lungs. But as the maestro is so fond of reminding me, I have another limitation to worry about.

"Feeling, Ms. Adams!" he says, his German accent as thick as his eyebrows. Every criticism begins with those same words, that same exasperated tone of voice that makes me want to crawl inside the music and hide behind the staff lines. "Beethoven wrote a piece full of passion. You're just playing notes on a page."

As if there's no passion to be found in that. In precision. One note under pitch, one late entrance, one sustain held a second too long and an entire piece can collapse into cacophony. And so I play in service to the way every single musical element comes together with mathematical rigor to form a seamless whole -- at least in theory. In practice, I am alone among my fellow musicians, the eccentric who refuses to impose some abstract sense of emotion upon technical perfection.

The maestro moves on to entreating the strings to give him a fuller, more bombastic sound. While he sings the phrase at them in that overly theatrical way of his, Josef, the principal flautist, tries to catch my eye from his seat two stands down. A subtle lean forward, an unsubtle smirk. He mouths "Mozart" and points to my music stand.

Great. Another one of his love notes.

I pull the Mozart concerto out from behind the Beethoven. Josef's handwriting, as artsy as that ridiculous beret he wears, fills the left margin:

You + me = plenty of feeling

. I'm amazed there isn't a slime trail to accompany the winking smiley face he's drawn. I grab a pencil from the lip of my stand and start erasing so vigorously that the music tears.

"Again," Maestro Fuhrmann calls out. "Top of the page."

Too quickly, I shove the Mozart back behind the Beethoven; the music crinkles. Too slowly, I raise my oboe to my lips; my entrance is late, my embouchure ill formed. I come in with an under-pitch squawk. The maestro glares in my direction. If there's one thing he despises more than my lack of feeling, it's amateurish mistakes.

When he finally calls for break an hour later, I rush from the stage, my eyes fixed on the floor. I manage to avoid Josef, but my escape route takes me past the conductor's podium, where I overhear the maestro muttering to the concertmaster about "reconsidering the sound of the orchestra." I've been here long enough to know what that means: at the end of the concert season, someone will be asked to leave. I don't need to guess which player he has in mind.

It's one disparagement too many. I flee to the bathroom and splash cold water over my burning cheeks. Our last music director was more forgiving of my "charming idiosyncrasies," as he called them. But Fuhrmann -- I'll never be able to give the man what he wants. The only feelings he's ever roused from me are embarrassment and shame.

By the time I've collected myself enough to head to the musicians' lounge, it's already 11:25 -- only five minutes of break left. I hurry across the room, cringing at the disarray that surrounds me. As ordered as we are onstage, neatly aligned by instrument and stand number, here the idealized, audience-perspective vision of an orchestra collapses. Chairs have been scattered every which way, dragged across the room so many times you can see their paths worn into the frayed carpeting. A half-played game of chess sits on one table; outdated magazines and days-old newspapers lie strewn across another. Kumiko is yakking on her cell, all the while monopolizing the copy machine with her pile of battered scores. Brendan from the trumpet section has taken up camp at the computer station. When he sets down his soda, he misses the coaster completely.

Josef waves for me to join him on the couch. I pretend not to see him and make a beeline for the kitchenette, where the scent of stale coffee does its best to cover whatever's been abandoned in the fridge this week.

In my rush for caffeine -- a necessity if I want to make it through more of the Beethoven -- I knock over a cupful of coffee stirrers. When I crouch to collect the ones that have fallen beneath the wobbly kitchenette table, I gasp in surprise at what I find. A large, flat circle covers the floor, as wide around as the head of a timpani drum, full of shimmering white and gold flecks. The flecks sparkle so much that I think they should be tinkling, yet they make no noise. A coffee stirrer teeters on the circle's edge, dipping up and down, the tip disappearing and reappearing, here and then not here. Curious, I tap the stirrer toward the circle. Without a sound or a ripple, it vanishes.

Josef is the first one to notice my discovery. He had probably been staring at my ass when I bent over. Again.

"What is

that

?" he asks, managing to make even the simplest question sound impossibly pretentious.

I reach toward the circle, hesitant. Did the stirrer fall through the floor? Vanish into another world? Or has it been snatched out of existence altogether? With Josef now squatting beside me, they all seem like appealing options.

"I wouldn't touch it," he says.

And so I do exactly that. Like the stirrer, my fingertips disappear into the glittering flecks. I expect to feel something -- pain, a prickle, liquid pooling around my skin. Anything. Instead, there's a frightening absence of physical sensation, as if my fingers no longer exist. A fingerless oboe player. With that dreadful image in mind, I yank my hand out of the circle. Suddenly my fingers are alive with sensation, every pore buzzing. I try to back away, to escape this overwhelming discovery, but the other musicians crowd around me, blocking my way. Their voices combine into a clamor that hurts my ears. That oaf of a percussionist T.J. shoves past them with such bumbling force that he knocks me forward, into the circle.

White and gold explode across my vision, vanish just as quickly. For a moment, I am suspended in nothingness. Everything I sensed only a second before is gone -- the scent of burnt coffee, the rough feel of the carpet beneath my knees, the oppressiveness of sweaty human bodies pressing in around me. Even the beat of my heart is silent in this void.

I smack against an iron-like grating, and sensation returns -- unfortunately. I feel not only my pulse racing, but also a sharp ache where my face connected with one of the grating's thick, black beams. At my feet sits the coffee stirrer, its formerly dull brown now vibrant against a featureless white floor. As I back away from the grating, I see that there are five beams in total, horizontal and evenly spaced apart. Another few steps, and more comes into focus: the swirl of a treble clef symbol, 2/4 time, one flat in the key signature, the instrument indication of "Oboe 1, 2." Too many measures of rest follow for me to tell if the key is D minor or F major, but I am definitely staring at my part on a musical staff.

I spin around. All around me, against an endless backdrop of white, are three-dimensional staves for woodwinds, brass, percussion, and strings. Overhead, title and composer loom large: Symphony No. 9, Beethoven.

D minor it is then.

I run my hands over notes and rests; their texture feels like the grainy metal of a music stand. I give an experimental tug at the staff lines -- sturdy enough that one could climb them like playground equipment. So many fantasies about escaping behind the staves, and here I am, standing in an oversized orchestral score. The entire piece has been rendered with a sculptural precision that makes me see Beethoven anew, that fills me with the kind of awe I felt the first time I ever laid eyes on the score's intricacies.

Though no instruments are in sight, the symphony begins. My surroundings are so pristine, so meticulous, that I half expect the tinny, synthesized playback of music notation software. What I hear instead is the sound of live instruments played with inhuman exactitude -- the horns on their sustained fifth, string tremolo lurking underneath. More parts join the sustain: clarinet, oboe, then flute, building and building until the theme the first violins have been hinting at bursts forth full force. I dart from measure to measure, grabbing hold of note heads so that I can feel their sound vibrating through me -- a sensation more thrilling, more intimate, than any human caress.

Feeling, Ms. Adams!

How delicious it would be to hear Maestro Furhmann right now.

Several of my fellow musicians stumble through the portal, cutting my musical reverie short. I stifle a shout of frustration. They could have burst into my home uninvited and I wouldn't feel nearly so encroached upon.

"What the hell is all this?" T.J. says.

Josef responds with an overly dramatic clap of his hands. "It's glorious, is what it is!"

They gasp and chatter and twirl about in circles, asking too many questions instead of watching and listening. It's just like rehearsal.

Josef slings his arm over my shoulders and drags me toward the woodwind staves, unsubtle in his babbling about the way the flute and oboe parts intertwine.

"So many people talk about losing themselves in the music," he says, "and here we quite literally have!"

Lose yourself in the music -- exactly the kind of thing I've never been able to do. At least not off the page.

And so it goes: a group of extremely talented yet overly spoiled musicians romp through Beethoven's 9th like children on a playground. They climb the staves and swap notes to hear how the trombone line would sound on the cello. T.J. and Brendan start a game of catch with a whole note. Kumiko rearranges the violin line the way she thinks Beethoven ought to have written it. Josef speculates aloud what it would be like to make love between the staves.