IGMS Issue 4 (11 page)

Authors: IGMS

Some of them fast.

Others languorous, creeping slowly and marking out a passage of aching beauty.

Jimmy tried to chart it at first, replaying sections over and over. His theory was rusty, but he managed to define a few note progressions before combinations of complexity went beyond him.

The sun disappeared, and almost immediately the wind came in, cold; whispering across the sands.

The longer he listened, the less Jimmy thought he understood the music. At times, he wasn't sure it was music at all. Among other things, he couldn't find any definite rhythm. The time signature eluded him, so that he could never identify individual phrases.

Finally, he stopped, putting his headphones aside and dropping to his elbows to watch the light go completely out of the sky. For a moment, he lost himself in the reassuring sound of waves upon the sand -- something he hadn't done once in all the time he'd been tracking the movements of the great ocean.

. . . learning the sounds of the earth, the sounds of nature, writing it down, learning the patterns . . . There's power in that, my friend. The power to undo.

Jimmy's gift had always been a very good ear. Any sound man worth his salt had one. Consumers rarely heard the difference, which explained the popularity of digital song downloads, in which compression technology had removed so much of the acoustic information.

Jimmy hated those. Not because they were free. Because they sounded thin.

Not like this.

The almost laughing sound of water rolling toward the beach came full-bellied, rich and strident every time. If the earth had a voice, this was surely it. And no place more certainly than this strip of sand on the Oregon coast.

But still something in it evaded him. If he could just understand.

Stories of Vaudevillians, old instruments, and warnings about his own musical incompetence only made him more eager to understand what it was he heard in his recordings. They may not want to see him profiting on the music of their beach here, but they wouldn't run him off with creepy stories. The thought of it made him laugh.

Hell, he'd lived in Los Angeles for eight years, nothing was creepier than that.

Then it happened.

Just reclining there on the beach, he began to count.

Simple eighth notes.

Seven of them.

Then again.

Jimmy sat up straight, staring at the water as if he expected it to talk. With alarming regularity, the water tumbled and fell to a beat of seven. The time signature carried its own power, but could scarcely be handled by most musicians. Standard time, swing time, the 3 count of a waltz, each of them could be danced to, internalized without training. Even phrases of two and five and nine fell more frequently in the music pantheon, adopted often by classical composers, used in songs with regularity.

But seven.

Jimmy counted, and counted.

When night had descended in full, something occurred to him. He quickly got his recording equipment from the car and set it up. This time, he dialed the frequency only half way in, and listened.

There it was.

The languished melody of the horn came in musical phrases to the beat of the surf. Jimmy now heard them together as he hadn't before, and in a flurry, he began to scribble out bars of seven, transcribing the song as it wafted and sang across the great time keeper.

So busy was he at his transcription, that he did not hear the rumblings deep in the earth. He exulted at the possibility that he might put definition to something that had never been written down.

He owed it all to the bugling of a horn. He owed it to George Henry.

The sky suddenly darkened and crackled with lightning. The waves swelled, a flurry of wind swept down upon the dunes.

All in perfect seven time.

Jimmy madly went on, oblivious to the changes around him.

Soon the tumult of thunder and pounding surf and shrieking wind became a chorus he might never have imagined. His papers riffled in his hand, but he held them tight, penning the sound in his ears, marking a great melody in bars of seven.

He knew instinctively that he'd become a conductor, and his orchestra was nothing less than the elements themselves.

He held the key.

He was unlocking the sounds of heaven.

Just like a Vaudevillian with a Gillespie horn.

In a fury, he put his pen back to the paper, marking out notes with haste, his hand flying across the page. The maelstrom whipped and churned, but all he heard were sevens, beautiful, indecipherable sevens.

Then he came to the end of his sheet, a single phrase yet to write, and paused as at the climax of a symphony, holding a great note before the finale.

And again he heard the old man, the minor thespian.

There's power in that, my friend. The power to undo.

With a single beat of his heart, he knew to decipher the song would make him forever a part of it.

Like a horn joined forever in the waves.

Jimmy shook with the feverish desire to unlock the mystery, to see his finding through its conclusion.

As the wind lashed and the water churned, he listened to another measure of seven.

And dropped his pen.

In moments the sea and air calmed.

Jimmy loosened his grip on his opus, the pages scattering about him, carried on mild breezes to the water's edge. He fell back and grabbed fists full of sand, imagining the difference between heaven and earth.

In the moments that followed, he could no longer count the rhythms of the ocean, its voice become again a mystery to him. But gentle it came, and it lulled his senses, like any good jazz music should.

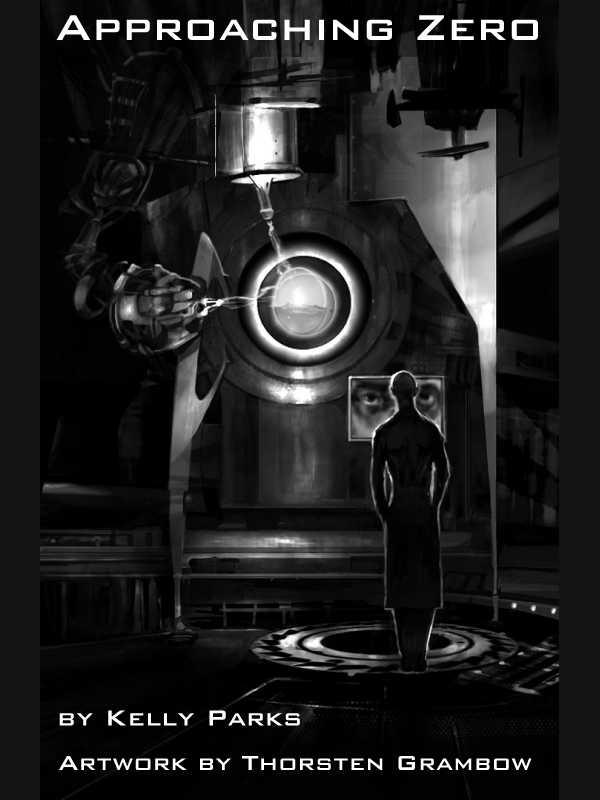

by Kelly Parks

Artwork by Thorsten Grambow

The girl at the desk was not so friendly anymore. She used to be, when my benefactor first set me up here on the 22nd floor. She used to be ditzy and friendly and childishly inquisitive about my work. But the pretense was gone now. Marta was Max's spy, here only to make sure my reports were honest.

And why wasn't she pretending anymore? Because it was over. I hadn't received official notification that the project was finished, but I felt sure the decision was made. It was a matter of days at most before the power was shut off and all the equipment went into storage.

She was intently surfing the net, undoubtedly shopping her receptionist/spy resume around to various wealthy madmen. I silently wished her luck, but didn't bother with conversation, having lost interest in pretense myself.

Past the reception area, down a hall with doors to small offices -- all unoccupied -- through a set of double doors and there I was: standing in front of the only gateway to alternate universes that had ever existed in human history. I built it and I should have won the Nobel Prize for it, but part of the agreement I'd made in exchange for the money to build it had been a thoroughly binding secrecy agreement. I'm pretty sure there was a clause in there somewhere about my soul.

Part of me still believed in miracles because there was a familiar feeling of hope as I switched on the equipment and began going through last night's logs, but it was quickly replaced by black despair as I saw that nothing had changed.

My cell beeped at me, the pattern telling me it was Max, or at least Max's office. I flipped it open and the tiny screen showed the fresh, young face of Art Samuelson, one of Max's lawyers. He smiled a sunny smile, waiting for me to accept the call.

I did. "Good morning, Art, " I said. No reason to be unfriendly. Lawyers can't help being what they are. No point in hating fungus for being fungus.

"David," he said. "Good morning to you! In the lab, eh? Never say die, that's you."

"The scans are getting much wider ranging now," I said, which was true. I was searching a bigger slice of infinity. "The results should be --"

"Dave," he interrupted in that pseudo-friendly way that you unconsciously want to believe. "You know I don't have a head for the tech stuff. Alternate universe, blah, blah, blah is all I hear when you talk about the details. No offense."

"None taken," I said. I sat down at my desk and put my phone on its stand.

"Davey, we've got a problem," he said. Here it comes. "All your gizmos are just drawing too much juice. The building manager has asked us to knock it off for a week or so until we can get an electrical contractor in there to certify everything. Sounds like a bunch of bull crap to me, probably designed to raise our rent. You know how these bastards are, right?"

I really had no idea which bastards he was talking about and felt certain the us vs. them invitation was meant to make me feel like we were in this together. A team. Go, team!

"Anyway," he said, "I need you to lay off the experiments until we can get this situation taken care of, okay?"

"Sure, Art. No problem. I can analyze the existing data for --"

"Excellent!" he said. "And, hey, how about lunch later this week? Max and I are doing that new Argentine place day after tomorrow at 11:30. Meet us there, okay?"

I nodded. He hung up.

I began charging the gate, planning on doing just what Art had asked me not to. There was a subtle whining sound from the equipment. Then inside the vacuum chamber a flickering light resolved into a small, silvery sphere less than a meter in diameter: the intersection between the four dimensional space-time of our universe and an infinite number of others.

I could never visit any of them. My still uncredited contribution to quantum mechanics had demonstrated that only massless particles like photons could pass between the universes. I swear, the moment I realized this could actually be done the first thing I thought of was selling the rights to TV shows from alternate universes. That's why I'd located in New York, a likely location for a city no matter what culture ended up here -- or so I'd assumed.

But of the many thousands of alternate Earths I'd examined through what I called the gate, no culture of any kind had settled here, because here was under at least ten miles of water.

That had never occurred to me. When I thought of alternate timelines, of course, I thought of worlds where the South had won the Civil War or the Roman Empire never fell. The appeal of that concept was why I'd specialized in quantum mechanics in the first place.

The universe didn't see things that way. I was still convinced that timelines did exist where human history had played out differently, but they were lost among the much more common worlds where life had never made it past the microbial stage, or where life had formed but had taken a completely different path and nothing remotely human ever appeared. It turns out that the evolution of multi-cellular life is a very low probability event and the evolution of intelligence lower still.

Another low probability event was the collision of the proto-Earth with a stray Mars-sized planet that resulted in the formation of the moon and the stripping away of a large fraction the early Earth's volatiles. Hence most versions of Earth were covered in vast, deep oceans.

"Would you like some coffee?" said Marta, startling me. She'd opened the door very quietly. Stealthily, one might say, like a spy.

"No," I said. "I won't need any help today, Marta. Why don't you take the rest of the day off?"

She smiled. "Oh, I'd love that! But I just can't. Too much paperwork." She shook her head in mock sadness at the mock paperwork, then left. I got up and locked the door, feeling certain that she had a key and that she was going to call Art as soon as she got to her desk. Damn it!

I'd gotten good at scanning universes -- or at least the tiny piece of each universe I could see through the gate -- very quickly. Panic made me want to just start scanning and keep doing it until they broke down the door and dragged me out, but reason reasserted itself. When searching infinity, how fast you do it is irrelevant.

So instead I stopped and looked at what the computer told me was alternate universe number 3809. All I saw was black. The bottom of a ten mile deep ocean is very dark indeed. It was lucky that only photons could pass through the gate. If I had opened a physical gateway to this watery Earth, the water pressure on the other side would have killed me instantly, and probably leveled the building. New York would be inundated in an alien ocean appearing from nowhere that wouldn't stop until the pressure was equal on both sides. How long would it take to flood the world? I shuddered.