I'm Just Here for the Food (29 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

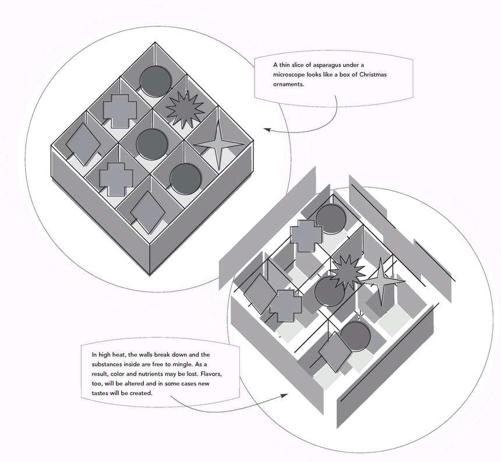

Now we drop the asparagus in rapidly boiling water. The temperature of the water drops quickly, but since we have a lot of water and leave the heat on high, the boil will recover soon. Almost immediately the cuticle and cement (pectins and whatnot) begin to soften from the heat and moisture. Within seconds the color begins to brighten because the oxygen and other gasses that were deflecting light away from the pigment in the chlorophyll dissipate out into the water. So do the acids that ordinarily would jump on those same pigments and turn them army green. Again, a lot of water will help flush those away as will a quick return to a boil, and an open pot (the gases have to be able to escape). If the target vegetable reaches satisfactory doneness before 6 or 7 minutes go by, you’ve got it made. The color, most of the nutrients, and the best of the flavor will be preserved. Pulling the food with a slotted strainer (good for working in batches) and moving it to ice water will immediately stop the destruction.

BOILING IN THE MICROWAVE

You want a cup of tea but you don’t want to wait for the kettle to boil so you take one of your really nice china cups and fill it with water. You place the cup in the middle of your microwave oven’s carousel and turn the big box to high for 3 minutes and go about your business.

Three minutes later the chime chimes and you pop open the door. Whistling a happy tune, you reach in and gingerly grasp the handle of your cup. You lift gently and without any warning whatsoever the water erupts out of the cup like Old Faithful with an attitude. A good portion of this water lands on your hand, scalding you badly. You drop your favorite cup (which breaks) and you howl like the injured animal you are.

How could this happen when the water wasn’t even boiling? A few reasons. In order to reach a boil there must be microscopic crags, chips, burrs, or cracks present on the surface for dissolved gases to meet and accumulate on. If the vessel in question is super smooth, the gases may not get together and undertake their bubbly journey. In the future, place a wooden skewer or even a toothpick in the water so that there will be coalescing points for the water vapor to gather. You’ll be glad you did.

But if that china cup has lead in the glaze, your fingers will still be toast.

STEAM: THE SHORT FORM

•

If you’re using unfiltered tap water, let it boil for at least a minute before adding the food and covering the pot.

•

Don’t waste time with a flavored liquid unless its on it’s way to becoming a sauce.

•

Use tongs and dry dishtowels or potholders when removing lids. Unlike boiling water, steam moves out and up very quickly—and it bites.

•

Season foods before steaming if possible. This includes salt and pepper. Marinating or brining is a good idea too.

•

Consider herbs. As steam heat pushes inward, it can take flavors with it, especially if the herbs have strong essential oils: try mint, basil, and members of the onion family.

•

Don’t go heavy on the water. One of the great things about steam is how fast it happens. A mere 1 cup of water in a 5-quart pot will produce steam for 15 to 30 minutes over medium-high heat, depending on the simmer range of the cook top.

What happens if you forget to pull the vegetables out in time? Think of a botanical prison riot. You see, the stuff in those little cells doesn’t necessarily get along, which is one of the reasons they’re in cells to start with. If the walls break down enough, those substances will begin to chew on each other, acid on base, enzyme on protein . . . it’s ugly. The gentle green pigments are the first to go, and the last are the fibers, the tough cellulose that so proudly held that little stem erect. And once the outer walls fail, those substances (including flavor and nutrients) will hightail it for the open sea. Now you’re faced with a choice: serve your disgusting, mushy veggies, or try to make soup with them.

Even with perfectly timed cooking, blanched vegetables won’t hold their color forever. Leave them sitting around in an acidic environment such as a salad dressing or a marinade and their color will be lost.

Blanching is also one of the easiest methods for peeling thin-skinned fruits such as peaches or tomatoes. That same cell breakdown that allows the color to brighten lets you remove the skin in a few quick peels, with no damage to the flesh underneath.

Steam

Through no fault of its own, steam has become the official cooking medium of the food inquisition, who use its power to inflict needless suffering on dieters who, thinking that if it’s bland it’s good for them, don’t know to fight back. But if used only for good, steam is a powerful ally.

Vaporous H

2

O is the result whenever heat produces enough molecular motion to break hydrogen bonds and enough internal pressure is generated to overcome atmospheric pressure.

Master Profile: Steam

Heat type:

wet

Mode of transmission:

65:35 percent conduction to convection ratio

Rate of transmission:

very high

Common transmitters:

any liquid

Temperature range:

213° F and up (depending on atmospheric pressure)

Target food characteristics:

• Delicate meats and vegetables that would be destroyed by the convection of boiling

• Wide range of vegetables

Culinary advantages:

steam doesn’t extract and wash away food components the way immersion methods do

Non-culinary application:

riverboat, locomotive, nuclear sub

I own two actual steaming devices. The first is a typical folding steamer basket (the kind that looks just like the laser-dealing satellite from

Diamonds Are Forever

, only without the diamonds). The second is an Asian-style bamboo steamer. Despite its ultra-low price tag I really, really dislike it. It’s amazingly inefficient, makes everything taste like dry grass, and is impossible to clean. But when my daughter was an infant, we needed a way to steam lots of vegetables at once while keeping them separated from one another before puréeing them and we needed something that would stack. I later discovered a company that makes metal stacking steamers, but the kid’s on to more solid fare, so I’ll pass.

I employ four different steaming rigs depending on the food in question:

• The collapsible metal steamer basket, a rapid-response tool that I grab when I’ve absolutely, positively got to get a green vegetable cooked and on the table in five minutes. I also use it to roast chiles over a gas burner.

• A pair of dinner plates in a wide, low pan (see illustration

A

).

• A steel colander with its handles crushed inward so that it’ll fit in a pot (

B

).

• Aluminum foil pouches (

C

).

Steamed Whole Fish

Application: Steam

Have the fishmonger clean the fish, remove the gills, and scale it for you. Using a clean utility knife that can be set to a specific depth, score the fish on each side by making diagonal slashes in the flesh, about ⅛-inch deep, in a cross-hatch pattern, 5 or 6 slashes per side. Rinse the fish under cold water and season with salt and pepper. Rub half of the garlic and shallots into the slashes and lay the fish on a plate. Set another plate face-down into a braising pan and add enough water to come two-thirds of the way up the side of the plate. Place the plate with the fish on top of the bottom of the plate in the pan. Pour the vinegar on the top plate. Bring the water to a boil over high heat and cover the pan. Steam for about 10 minutes. Check the fish for doneness by gently lifting at the flesh with a fork. When it easily pulls away from the bone it is done. Carefully lift the fish to a serving plate and loosely cover with foil. Carefully pour the liquid that has accumulated on the top plate into a small sauce pan and heat the

jus

to a simmer. Heat a sauté pan and add the oil. When the oil is nice and hot, add the remaining garlic and shallots and sauté until brown. Add the chile flakes and basil and fry for a few seconds. Remove the foil from the fish and pour the hot oil over it. It will make a sizzling noise as the skin fries. Serve immediately, with a ramekin of the simmered

jus

on the side.

Yield: 1 whole fish for one person, easily doubled

Software:

1 (1-pound) whole round fish

(Snapper, rockfish, or sea bass

are good choices)

Kosher salt

Freshly ground black pepper

2 tablespoons thinly sliced garlic

2 tablespoons minced shallots

¼ cup herbed vinegar such as

tarragon or basil

¼ cup olive oil

1 teaspoon chile flakes

1 tablespoon fresh basil, cut into

fine chiffonade

Hardware:

Clean utility or matte knife

Braising pan with lid (or aluminum

foil to cover)

2 steamproof plates large enough

to hold the fish and fit into

the pan

Small sauce pan

Sauté pan

Serving plate

Savory Savoy Wraps

These little gems are easy and delicious. You can make them as large as an egg roll or as small as a dolma depending on the size of the leaves.

Application: Steam

Lightly blanch the cabbage leaves so that they can be rolled without breaking (see

Note

). In a mixing bowl, combine all the ingredients except the cabbage leaves and season the filling with salt and pepper. Lay out a cabbage leaf, inside down (it’s greener and prettier), and make a small pile of filling in the center. Roll into a tight package. Repeat with remaining leaves and filling, placing the rolls in a steamer basket, seam side down. Put enough water in a pot to come almost to the bottom of the steamer and bring to a boil. Put the lid on the pot slightly askew to allow steam to escape. Steam for 8 to 10 minutes.

Yield: 2 servings (or 4 appetizers)

Note:

To blanch the leaves, simply immerse them in boiling salted water for 30 seconds and then immerse them in ice water to cool. Drain and pat dry with a towel.

Software:

8 large Savoy cabbage leaves

½ pound sweet Italian sausage,

cooked and crumbled

1 cup peeled apple slices

1 teaspoon cinnamon

1 cup finely diced potatoes

Kosher salt

Freshly ground black pepper

Hardware:

Mixing bowl

Large pot

Steamer basket