I'm Just Here for the Food (41 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

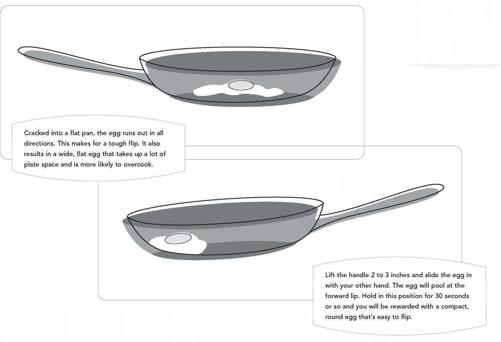

3. Unless you’re using a very small pan—say four inches across—resist the urge to crack your eggs directly into the pan. Instead, break them into a small tea cup or ramekin. Why? So you can do this:

With the exception of sunny side up and scrambled, egg preparations get at least one flip, but knowing

when

to flip the flip is a little tricky. I like my eggs over easy, which means that the whites are nicely set but the yolk is lavalike: flowing, but not runny. I don’t flip until the thick albumin immediately surrounding the yolk is almost opaque. Then I flip (see Age Matters) and count to 15 slowly. Then I flip again (so that the yolk is visible once again) and slide it onto a plate. At no point do I ever touch the eggs with a spatula—that just invites trouble . . . and yolk breakage. If I’m making a full-blown fried egg, I flip at the same time, but I let it cook a full minute more before plating. In other words, I always execute the first flip at the same state of doneness. What differs is how long I cook it on the second side.

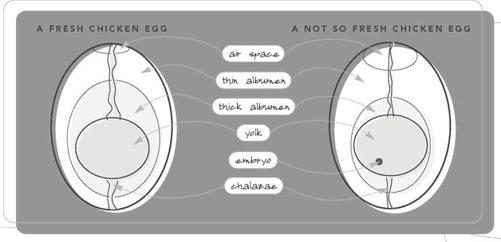

AGE MATTERS

Eggs have a multilayered construction. Besides the outer shell, there is a thin white or albumen, a thick albumin, the yolk, and the chalazae. This last item is basically a bungee cord of egg white that keeps the yolk (and the microscopic embryo that’s attached to it) in place. These layers are separated by membranes, which deteriorate as the egg ages. That means that an older egg (say, one month old) is going to be a beast to cook over easy, because the odds are good that the yolk is going to crash when you turn it. On the flip side, this same egg would be a heck of a lot easier to peel if cooked hard, because the membrane between the outer white and the shell will be less resistant.

There are, of course, exceptions to the low-temperature rule. Frittatas, soufflés, and meringes all require higher heat because they need to:

• expand. This requires one of two things: either water must turn to steam before the egg sets, or air bubbles physically trapped in the matrix must expand, again before the egg sets. Both scenarios require high heat.

• brown via the Maillard reaction. It’s important to note that in this case other ingredients are always present. Eggs should never be left to face high heat alone.

Buying and Storing Eggs

Eggs are bathed, sanitized, dried, and then candled at processing plants. Specially trained workers can spot irregularities and mark a bad egg; the computer remembers that egg and removes it down the line. Eggs that pass muster are weighed by a jet of air and sent to the appropriate cartons.

A dozen medium eggs weigh a minimum of 21 ounces, a dozen large weigh 24 to 26 ounces, a dozen extra-large have to tip the 27-ounce mark, and a dozen jumbo are a robust 30 ounces. At only 15 ounces per dozen, the peewee size don’t find their way to the breakfast table and are used instead for industrial purposes.

Egg size doesn’t necessarily correlate to egg quality; a grading system serves that purpose. Egg grading is voluntary, and falls under state statute, but many egg processors leave the chore to on-site USDA inspectors. The different grades of eggs are AA, A, and B. Double-A eggs are your freshest eggs. The white is firm and stands up when the egg is cracked open and the yolk is rounder. The difference between AA and A is mainly the age of the egg: an A-grade egg is just a little older than an AA. (So, somebody could buy a dozen AA eggs, take them home, leave them in the refrigerator for a couple of weeks, and they would drop to grade A.) A B-grade egg is good and clean on the outside but when twirled in front of the light you can see the shadow of the yolk. The reason you see the yolk that plainly is because the membranes have broken down. So, when you crack it into your pan or onto a plate it’s going to run out.

Eggs usually make their way to your market within a week of being laid and are a staple item that pretty much flies off the shelf; old eggs are a rarity. The Julian date (not the “use by” date) tells you when a carton was packaged. It will be a number between 1 and 365, representing the day of the year on which it was packaged.

When you peek into a carton of eggs checking for cracks, also check to see that the eggs are cold. A room-temperature egg ages more in a day than a refrigerated egg ages in one week. Keeping the fridge at or a little below 40° F will help keep eggs fresh. So will keeping eggs in their carton toward the back of a shelf. The nice little egg shelf found on many refrigerator doors is cute, but that door spends too much time open, hanging out and heating up. Plus, shelf bins promote drying and breakage.

RISK FACTOR

One in ten- to twenty-thousand eggs may be infected with

salmonella

, and even if an egg were infected, the

salmonella

level would probably be too small to harm a healthy adult. It’s advisable, however, that older folks, expectant mothers, young children, and anyone with immune system problems steer clear of undercooked or raw eggs. That means passing on sunny-side up eggs, homemade mayonnaise, hollandaise, eggnog, and classic Caesar salad.

Scrambled Eggs

Ask a French chef to scramble you a few eggs and you’re likely to see him whisk a few eggs together with a bit of heavy cream, then cook them in a double boiler over simmering, not boiling, water. I’m often annoyed by the persnickety extra steps that French cuisine demands, but this time I must agree. It’s not that it’s impossible to make good scrambled eggs straight in a pan, it’s just that the double boiler guarantees that the cooking will be done at a steady temperature and at a relatively low rate of conduction.

Don’t forget to garnish. A sprinkling of fresh herbs, especially chives, does wonders for scrambled eggs. The best plate of scrambled eggs I ever had (far better than the best omelet I ever had) was finished with truffle oil and sprinkled with finely minced red onion and a dollop of caviar.

Application: Simmering

Pour an inch or two of water into a heavy sauce pan and bring to a boil. Lower the heat until bubbles just break the surface (okay, I’ll say it: a simmer). Place a heavy metal bowl over the sauce pan and put the butter in the bowl. Make sure that the bottom of the bowl doesn’t come anywhere near the water below.

In a separate mixing bowl, whisk the eggs together with the cream and salt. You don’t have to get this completely smooth, but the more homogenized the mixture, the smoother the finished eggs will be.

When the butter has melted, add the egg mixture to the heated bowl. Now, when and how you stir with a plastic spatula will go a long way toward determining the final texture of the eggs. The desired action isn’t so much stirring as it is scraping. As the egg cooks on the surface of the bowl, scrape it away so that a fresh coating of the egg mixture can come into contact with the metal. These sheets of cooked egg form lumps known as “curd.” Continuous scraping will result in a very fine curd while less frequent scraping produces larger curd. The choice is entirely yours, and you should play around with your technique a bit until you find one that suits your taste. As soon as there is no liquid left in the bowl, pull it from the heat, and move the eggs onto a plate. The eggs may not look done, but they’ll continue to cook and will be just right by the time you take your first bite.

Yield: 1 serving (see Note)

Note:

I consider 3 eggs a single serving. To increase, double the recipe for each additional diner.

Software :

½ tablespoon butter

3 large eggs

1 tablespoon heavy cream

¼ teaspoon kosher salt

Hardware :

Heavy sauce pan

Heavy metal bowl large enough to

fit into the saucepan, with a

couple inches of lip to spare

Mixing bowl

Whisk

Plastic spatula

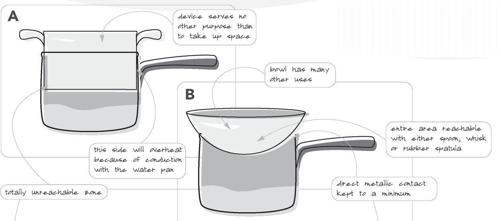

DOUBLE BOILERS

I think that America’s general disdain for double boilers comes from the fact that many pot manufacturers insist on making them despite the fact that they are useless, silly uni-taskers that can’t even do the one job that they’re meant to do.

Figure A. Just look at this silly thing. You can’t get a whisk, spoon, or spatula into the corner. The entire side is in contact with the bottom pot. Remember conduction? Heat’s going to move right up the side of the bottom pan into this vessel. Worst of all, this vessel has no other use that I can find except take up space and collect dust. Silly, I tell ya.

Figure B. Ah, logic. A metal mixing bowl is whisk and spatula friendly. Contact with the bottom pan is minimal, and the edge of the bowl extends well beyond that of the pan. This may not seem like a big deal, but that span gives heat a place to dissipate and it prevents steam from condensing and rolling down into the food, which is especially important when dealing with chocolate, which will seize into a gnarly mass at the mere mention of water.

Poached Eggs

Once they invented cooking, the French set out to name everything involved—and poaching is no exception.

Poach

comes from the French

poche

for “pouch” or “pocket” and refers to the shape of an egg cooked in barely simmering water. I suppose it’s right that the method be named for the dish, because there is nothing as sublime as a properly poached egg.

Many cooks prefer a deep-water method that allows the egg to form more of a…well, pouch. I prefer this shallow-pan method because it produces a more horizontal—and therefore more plate-able—

oeuf

. My favorite way to serve poached eggs is on top of a salad of bitter greens. Poached eggs can also be cooked ahead of time. Simply move the cooked eggs straight from the pan to a bowl of ice water and hold them there for up to 8 hours. Bring them back to heat in a quick (no more than 1 minute) bath in simmering water.

Application : Poaching

Break the eggs into small custard or tea cups.

Pour enough water into a 10-inch non-stick sauce pan or sauté pan to come halfway up the side of the pan. Bring to a boil over high heat.

When bubbles start to beak the water’s surface, stir in the salt and the vinegar.

Slide the eggs gently into the pan by holding the cups as close to the surface of the water as possible. Arrange them at twelve, three, six, and nine o’clock.