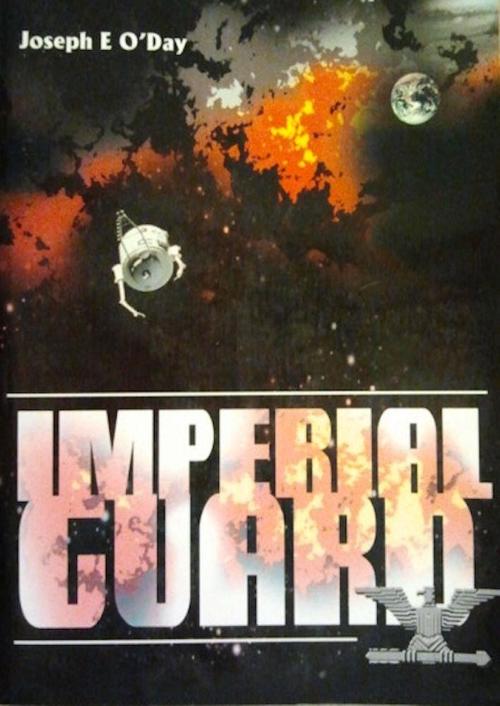

Imperial Guard

Imperial Guard

Joseph O’Day

© 1992, 2000 by Joseph E. O’Day

To Ralph J. O’Day, Jr.,

my

older brother,

who

wrote the rough draft of

the

first few chapters of this novel,

and

without whom this adventure

would

not have been created

THE DANIEL MIZPALA FACTION

Timothy Brogan

John Manazes

Andrew

Darkhow

Dar Unger

Izel Calderon

THE KEPEC MOGUL FACTION

Carl Mogul

Josh Mogul

Monod

Akard

Officials of the Trading Company

| 2032 | Pacific Alliance |

| 2056 | Nuclear and biological holocaust |

| 2086 | Self-contained hydrogen engine developed |

| 2089 | Moon Base established |

| 2094 | New Western Capital established in Rio |

| 2095 | Mars Base established |

| 2098-2115 | Interstellar |

| 2158 | World Empire |

| 2217 | Hyperjump discovered |

| 2226 | Uniform Code of Military Conduct |

| 2264 | Timothy Brogan born on Cirrus |

Leaning on his hoe, Timothy Brogan wriggled his toes into the soft, hot soil, searching for the

coolness that would soothe his scorched feet. The rising heat made waves in the distance, and the shimmering, green plants stretched out in trim, straight rows in every direction.

It’s too hot a day for such drudgery

, he silently complained. But heaving a sigh, he hoed on for fear that his eternally vigilant father might once again shout him into action.

As the minutes passed, his hoeing slowed, then stopped altogether as he glanced upward to see a tiny sliver of silver, trailing vapor against the dark-blue sky of Cirrus. Once again he drifted into his favorite daydream, and in his imagination he was piloting that very ship

—docking with the orbiting space station and taking off once more to travel to distant stars. The best part of the daydream was when he saw himself strutting down the streets of nearby Ebinezer in the blue-and-white uniform of the Imperial Navy, followed by the admiring eyes of the townsfolk.

But deep inside Timothy knew that his dream of piloting one of those sleek battle cruisers, or even a freighter, across the galaxy was just that

—a dream. Fact was, he would be content just to pilot the small scout ships that rode piggyback on the larger cruisers or freighters, or even to fly the shuttles between station and planet. His overwhelming passion was to get into space and off this backward planet, no matter what form it took. Folding his hands over the top of the hoe handle, he dropped his head and shook it, as if to loosen the tangled cobwebs of a romantic fantasy. It would never happen. Still, he could dream.

A shout violently jerked him back to the present. Amos Brogan gestured across the patch of melons. “Get movin’, son! Ya haven’t budged since I last looked! Ya haven’t got all day t’ finish that row. Our time in the private patch’ll be up soon enough.”

With a grimace, Timothy resumed his methodical motions. But he had to agree with his father. Time in the private patch was precious. It was almost their only source of cash income, and time spent in it must be used wisely.

The rules were firm. Only one day out of the week could be used for private enterprise. Cirrus was a frontier world, and the Trading Company, which had financed the pioneers’ immigration five decades ago, required payment in trade. Only the Mennonites had been able to win the concession of an additional day to rest on the Sabbath. But the cost was high: two generations of trade before they gained their freedom and the ownership of their land. Amos was the second generation, and when Timothy reached the age of twenty-one, four years from now, the land would become theirs.

What a day that will be for the family!

thought Timothy.

If only my grandfather had lived to see it.

But even in this age of interplanetary travel, the life of the pioneer was hard. His father was only sixteen when Grandfather died. Timothy had never known him. After the Company approved Amos’s petition to continue his father’s bondage, he had had to make great sacrifices. By living frugally and by skillfully marketing their private produce, he was able to save enough money to rent the Company planting and harvesting machinery needed each year for his two thousand acres of wheat. It had been a determined struggle, and, without realizing it, Timothy took great pride in his family’s accomplishments.

Wheat was the fuel of the Empire. In the long history of humankind it had always been so, and things had not changed. Earth had long ago outstripped her agricultural resources and now depended largely on offworld imports. The nuclear and biological conflagration two centuries ago had rendered immense areas of the northern hemisphere uninhabitable and untillable until recent decades. It had taken only a couple generations for the radiation levels to subside, but the chemical and biological weapons launched by China and the Islamic Jihad effectively shattered the ecological infrastructure of the North American continent. It was only the huge freighters plying their routes between the stars that kept the crowded and food-deficit world alive.

The demand for offworld produce was high, for Earth nobility lived in style. Like their historical counterparts

—Rome, England, America, Europe, and the Pacific Alliance—the wealth of the Empire flowed into Imperial Earth. The Emperor and his minions maintained strict control over emigration and extracted a heavy toll from all who wished the arduous life of the pioneer. They were indeed happy to see some groups leave, but they never let that stand in the way of a profit and were careful to ensure an ever-increasing amount of trade. Radical Muslims were one such group. The Mennonites were another.

Timothy’s great grandfather, of Scotch-Irish origin, became a Mennonite as a boy, even though most of his Mennonite brethren were of German descent. Mennonites did not approve of artificial birth control, even though it was extremely cheap and easily administered. Their propensity for large families, therefore, made them extremely unpopular on an already overcrowded earth. They were also undesirable to the authorities because of their firm convictions and their counterculture mentality. However, they were conscientious and law-abiding. Therefore, they were selected as the group most likely to remain loyal and cause the least trouble on a frontier world. As it turned out, that was an unfortunate miscalculation.

When word broke that the Empire was opening a new agricultural world and only Mennonites would be allowed emigration, Timothy’s grandfather signed on. Many non-Mennonites converted to the faith just to take advantage of this new opportunity. Most Mennonites despised city life, but after planetfall these pseudo-believers soon gave up their farming and began building villages. The Empire tacitly allowed this deception, because they knew such profiteers would build the towns and cities required by a new world.

Still day

dreaming as he worked, his hawklike features relaxed and his gray eyes unfocused, Timothy carefully pulled dirt around each young plant and sliced off the roots of the weeds with his sharp hoe. “I’ll bet pilots of the Imperial Navy don’t have to do dumb work like this,” he muttered.

Tomorrow the Navy recruiter would arrive, and Timothy, like most of the other eager youngsters at school, planned to take the test for the Academy. Though he had trouble keeping his mind on any one thing for long

—unless it concerned piloting or navigation—Timothy had a sharp mind. He was not a deep thinker, but he grasped facts quickly and seemed to know instinctively how to use them to his advantage. He did not have an impressive physique, but he was wiry and used to hard work. He had the internal drive to push his supple frame to the limits of its endurance if necessity demanded it.

The light was fading when Amos called a halt to their work. By the time they got back to the yard it was dark, and the friendly light from the house windows beckoned. But the chores had yet to be done. The animals must be put up for the night, the stock fed, and the cows milked. Every day it was the same. There was no reprieve. Failure to follow the routine confused the animals, and they would not cooperate. Still, Timothy hated it.

The barn was fairly pleasant in winter, but now that the heat of summer was upon them, it was far too warm for comfort. “Hurry up with that milkin’, son,” called his father gruffly. “Ma’s puttin’ dinner on, and the food’ll be cold soon enough.”

Light spilled across the barnyard from the kitchen window, providing the only illumination as Timothy scuffed wearily up to the house, lugging the brimming milk can. But tired as he was, he took great care pouring it into the cooler. Not a drop could be wasted. He learned this lesson years ago from the severe thrashing his father had given him because of his carelessness. The young boy, smarting from the beating, supposed his father had never heard the ancient expression, “No need crying over spilt milk.” But never again did he let his mind wander while he poured the milk.

“Come on, Timothy. Supper’s ready,” sang the voice of Lydia Brogan.

“Coming, Ma.” It was customary for the eldest son to sit to the right of his father. Timothy sat down heavily in his usual place.

Lydia Brogan was a strong woman, but that was not unusual on a frontier world. Such planets required women of strength, not only in body but in character. Many died before they were fifty, burned out from the hard work and the bearing of many children.

Children were an economic necessity to the frontier farmer, for they made his work easier, and they were much cheaper than robotics. Lydia herself had only six. Her last child, Rachel, had given her such a difficult delivery that the midwife told her she could have no more. But Lydia was content.

Luke was next to the youngest, and before giving thanks, Amos admonished him: “Luke, see that ya keep yer head bowed and eyes closed for the blessin’. You’re old enough t’ sit proper now.”

“Yes, sir,” replied Luke. Now five years old, he had already learned how to address his elders.

Timothy’s mind began to wander as his father began the lengthy recitation of praise and thanksgiving. He began to think again of the approaching examination for admission to the Imperial Naval Academy. He could already picture himself in that blue-and-white uniform. But if his father even suspected his plans, there would be trouble. If accepted, he’d have to sneak away without telling anyone.

So he must make good on his first try. There would be no second chance. If caught, his father would summon the elders of the church, and under solemn vow he would be forced to promise never to do it again. Even though Timothy was a half-hearted believer, he knew he could never break such a vow. A sudden silence broke his reverie, and he realized with a start that the prayer was over.

“I thought perhaps ya’d gone to sleep,” observed Amos, the narrow, penetrating eyes within his deeply seamed face half-critical, half-facetious.

“N-no,” stammered Timothy, “I was just finishing a prayer of my own.”

“School’ll be over in three days’ time,” continued Amos, ignoring his son’s discomfort, “and the wheat’ll be ready for harvest. This year it’s our turn to use the Company machines first. Being last a year ago cost us our bonus, what with the early rains and all. But it looks good we’ll get that bonus this year.”

Last year the church had to advance the Brogans some credits or the Company would have extended their bondage another year. The loan would have to be repaid this year. But Amos had further news: “The elders have decided that they’ll consider the loan repaid if Timothy does a man’s share of the work for the harvest season.”

Timothy perked up eagerly. “Will I get to drive one of the harvesters?” he asked excitedly.

“No, son. You must work in the storage tanks at the freight yard.”

Timothy’s expression melted. That was the dirtiest and most difficult job of all. Noting his reaction with a grin, Amos slapped him on the back. “Hard work is good for the soul, my boy! You’ll make out fine!”

No matter how many times Timothy heard his father say that, it never seemed to help. So in an effort to escape the harsh reality of the next few weeks, he submerged himself once again into wishful thinking.

Despite his rebellious streak, he was grateful that his father and the church placed such a strong emphasis on education. The first generation born on Cirrus learned mostly on its own. Time was considered much too precious to spare for formal schooling, and Amos felt the loss keenly. He was determined, no matter what the cost, that all his children would complete at least their basic schooling at the church school.

A few years ago, when a used transit bus became available, he was instrumental in getting the church to buy it so that the farmers could send their children on to complete their education at the public school in Ebinezer. Because Timothy was able to continue his education, he was now in a position to take the Academy test tomorrow and, hopefully, to realize his dreams.

When dinner was over and all the chores completed, Timothy hurried to his room. Now he could steal a few precious minutes with his scan before falling asleep. A “scan” was a small, pocket-sized computer that projected an adjustable three-dimensional visual of the selected file. Thousands of books could be stored in it, and now Timothy selected one he had been meaning to get to for several days.

The only real books Timothy had ever seen were the worn Bibles brought from earth by the first settlers, but it too had made the transition to computer. Even though humanity kept expecting to outgrow its ancient truths, it continued to survive and to attract a following.

Shortly before the Great Conflagration, developments in computer technology had reached an astonishing level. Many computer generations after the first primitive models in the midtwentieth century, experts finally succeeded in their goal of creating true artificial intelligence. Then they joined the artificial with the natural and grew the first biological computer. Machine and organism became one. A computer had become a living entity.

But this development was frightening and unsettling

to many people, and in the postwar decades an anti-computer movement gained momentum. It had been decades since the Empire declared biological computers illegal and placed severe restrictions on the use and application of artificial intelligence. Still, it was well known that small enclaves of renegade computer scientists continued to exist. They believed that scientific progress should not be restricted for any reason. The scientific community as a whole, however, had long ago abandoned that notion as sociologically naive.