Imperial Stars 1-The Stars at War (47 page)

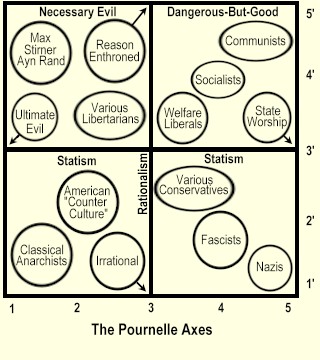

The two I chose are "Attitude toward the State," and "Attitude toward planned social progress."

The first is easy to understand: what think you of government? Is it an object of idolatry, a positive good, necessary evil, or unmitigated evil? Obviously that forms a spectrum, with various anarchists at the left end and reactionary monarchists at the right. The American political parties tend to fall toward the middle.

Note also that both Communists and Fascists are out at the right-hand end of the line; while American Conservatism and US Welfare Liberalism are in about the same place, somewhere to the right of center, definitely "statists." (One should not let modern anti-bureaucratic rhetoric fool you into thinking the US Conservative has really become anti-statist; he may want to dismantle a good part of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, but he would strengthen the police and army.) The ideological libertarian is of course left of center, some all the way over to the left with the anarchists.

That variable works; but it doesn't pull all the political theories each into a unique place. They overlap. Which means we need another variable.

"Attitude toward planned social progress" can be translated "rationalism"; it is the belief that society has "problems," and these can be "solved"; we can take arms against a sea of troubles.

Once again we can order the major political philosophies. Fascism is irrationalist; it says so in its theoretical treatises. It appeals to "the greatness of the nation" or to the volk, and also to the fuhrer-prinzip, i.e., hero-worship. Call that end (irrationalism) the "bottom" of the spectrum and place the continuum at right angles to the previous "statism" variable.

Call the "top" the attitude that all social problems have findable solutions. Obviously Communism belongs there. Not far below it you find a number of American Welfare Liberals: the sort of people who say that crime is caused by poverty, and thus when we end poverty we'll end crime. Now note that the top end of the scale, extreme rationalism, may not mark a very rational position: "knowing" that all human problems can be "solved" by rational actions is an act of faith akin to the anarchist's belief that if we can just chop away the government, man truly free will no longer

have

problems. Obviously I think both top and bottom positions are whacky; but then one mark of Conservatism has always been distrust of highly rationalist schemes. Burke advocated that we draw "from the general bank of the ages," because he suspected that any particular person or generation has a rather small stock of reason; thus where the radical argues "we don't understand the purpose of this social custom; let's dismantle it," the conservative says "since we don't understand it, we'd better leave it alone."

Anyway, those are my two axes; and using them does tend to explain some political anomalies. For example: why are there two kinds of "liberal" who hate each other? But the answer is simple enough. Both are pretty thorough-going rationalists, but whereas the XIXth Century Liberal had a profound distrust of the State, the modern variety wants to use the State to Do Good for all mankind. Carry both rationalism and statism out a bit further (go northeast on our diagram) and you get to socialism, which, carried to its extreme, becomes communism. Similarly, the Conservative position leads through various shades of reaction to irrational statism, i.e., one of the varieties of fascism.

On the anti-statist end of the scale we can see the same tendency: extreme anti-rationalism ends with the Bakunin type of anarchist, who blows things up and destroys for the sake of destruction; the utterly rationalist anti-statist, on the other hand, persuades himself that somehow there are natural rights which everyone ought to recognize, and if only the state would get out of the way we'd all live in harmony; the sort of person who thinks the police no better than a band of brigands, but doesn't think that in the absence of the police, brigands would be smart enough to band together. The whole thing looks like Figure One. (In Jim Baen's Editor's Note at the end of this article.)

Now I do not claim this is

the

model of modern politics; I do claim that it is a far better model than the one we're using, and in fact I go farther and claim that the "left-right" model so ubiquitous amongst us is harmful. And while I understand that some ideologues find the "left-right" model useful to their cause, and thus have a powerful incentive to gloss over its failures, what puzzles me is why so-called objective political "scientists" don't try to abolish it, at least in freshman political science classes.

But then I've already admitted I don't understand the "social sciences" to begin with, and I needn't say all that again.

EDITOR'S NOTE:

Never before have I felt called upon to add to one of the redoubtable Dr. Pournelle's columns, but Jerry has been guilty of that most heinous of auctorial sins: modesty.

Seriously, Jerry seems to have come up with a useful, predictive,

scientific

measuring device for the social so-called sciences, and passed it off as an "Appendix," forsooth! In politics alone the results of the widespread use of the Pournelle Axes would be revolutionary: pols would be required not only to declare themselves but to reveal precisely and literally their political position—and live with it. For example Teddy Kennedy from his own pronouncements cannot be less than a 4.5/4.5'—how many people in this country would vote for a 4.5/4.5' once it was revealed for what it was? Give me a 2/4'

any day! (That's what

I

am; once you have analyzed your own position, you may find your own political choices becoming remarkably simplified. Reagan and Crane, both at 4/2', make me a little nervous. Bush, at 3/3', looks pretty good.)

Note also the odd sympathy and support between the diagonally facing quadrants, as opposed to the antipathy between contiguous ones—at first blush diagonals would seem to make natural enemies, yet artists, intuitive by definition and anti-statist almost by definition, yearn for a world where true art is replaced by Socialist Realism—while

libertarians

provide the theoretical groundwork for right-wing dictatorships! Odd, very odd.

Note also how one can define "reasonable" as any position no farther from 3/3' than one's own: those farther out in one's own quadrant are pleasantly dotty; those farther out in another, unpleasantly so . . .

But it's not my aim to analyze the Pournelle Axes in depth; any such attempt by me would be necessarily superficial. One of these days I'll get another column from him on this subject. My point is that for

this

column Jerry Pournelle is guilty. Guilty as sin. Of modesty.

—Baen

Destinies

isn't the only work James Patrick Baen and I have created in collaboration. When he was over at another publishing house we together generated a series of anthologies which I wanted to call

Future Men of War

; but which Jim insisted on calling

There Will Be War

despite vigorous arguments that the title would kill all its sales.

He must have done something right: the series is in six volumes with a million copies in print; and we are at work on volumes seven and eight.

That, of course, is the genesis of

Imperial Stars

: a series that might be called

There Will Be Government

. Of course that doesn't sound so exciting. Or does it? Empires rise and fall; republics come and go; we seek perfection, and we may or may not find it; but the manner of our seeking is terribly important.

The next volume of this series will be called

Republic and Empire

; and will contain stories and essays on the strengths and weaknesses of those forms of government, and of the conflicts and wars between them. We will look at the matter of conscription, and what obligations (if any) a free citizen owes to government. We will continue my speculations about all ends of the political spectrum, and our search for a real science of politics.

Well do all this our way, which is with good stories that entertain as well as instruct.

Finger Trouble

Edward P. Hughes

Everyone knows how we came to be. There was a primordial Big Bang that created the Universe from nothing. This made a lot of hydrogen and helium, which sort of clumped into stars, which cooked new higher elements and eventually exploded. New stars formed, and planets; and on some of those planets there was a kind of organic soup, and—

There was a cartoon once. Three white-coated scientists looked at a blackboard covered with equations. Step by step the equations proceeded, until, in about the middle, were written the words: "And then a miracle occurs." The equations continued. The caption was, "Now, Dr. Hanscomb, about that eighteenth step . . ."

After life swam out of the organic soup we had Darwinian evolution. Everyone knows what that is. And of course it must be correct; after all, our schools are now required to teach it.

Sir Fred Hoyle, who knows a little about the origins of the universe, has some harsh words for all this. For example:

". . . nothing remains except a tactic that ill befits a grand master but which was widely used by staunch club players, namely to blow thick black pipe tobacco smoke in our faces. The tactic is to argue that although the chance of arriving at the biochemical system of life as we know it [through random action] is utterly minuscule, there is in Nature such an enormous number of other chemical systems which could also support life that any old planet like Earth would inevitably arrive sooner or later at one or another of them.

"This argument is the veriest nonsense."

In their work

Evolution From Space

Sir Fred Hoyle and Chandra Wickramasinghe argue that life throughout the universe has arisen by

design

. They don't deny that most life on Earth, including human beings, evolved from simple forms that first appeared on the planet some millions of years ago; but they claim that the evolution was

directed

. Darwin was simply wrong.

This isn't as new an hypothesis as you might think. After all, most of us were taught in high school biology the cellular theory: "Omnia cellula e cellula," said Schleiden and Schwann. All cells come from other cells. There is no spontaneous generation of life. This was accepted well into this century. Arrhenius, Nobel Prize winner for chemistry in 1903, argued that life pervades the universe, and is carried across it in spore form. Life was no more spontaneously generated in Earth's primordial organic soup than is the serpent of Egypt born in the mud "by the action of the Sun." Thus believed Pasteur; thus believed everyone. Except they didn't.

Hoyle and Wickramasinghe: "Yet by a remarkable piece of mental gymnastics biologists were still happy to believe that life started on Earth through spontaneous processes. Each generation was considered to be preceded by a previous generation, but only so far back in time. Somewhere along the chain was a beginning, and the beginning was a spontaneous process.

"Most but not all. Even in the nineteenth century there were a few scientists who felt the situation to be contradictory. If spontaneous generation could not happen, as Louis Pasteur had claimed to the French Academy, then it could not happen. Every generation of every living creature had to be derived from a previous generation, going backward in time to a stage before the Earth itself existed. Hence it followed that life must have come to the Earth from outside."

And indeed, according to Hoyle and Wickramasinghe, that is exactly what happened. Not only that: although there is a chance element in evolution, we continue to receive new genetic material from space to this very day. There is Evolution From Space, and it is not yet completed.

Their conclusion is remarkable: there is only one chance in ten to the fortieth—ten followed by forty zeroes—that life arose spontaneously by chance.

After all: if you put all the parts of a watch into a barrel, you can shake the barrel until doomsday and the parts will not fall together into a watch. If you find a watch in the woods, does that not imply a watchmaker? And if you find a watchmaker?

It simply isn't true that if forty million monkeys sat at typewriters they would eventually produce all the works in the British Museum. If every molecule in the universe were a monkey complete with typewriter; if those monkeys had all begun typing at the moment of the Big Bang, and each monkey had produced one English character each second—the chances are no more than one in ten to the twentieth that among them they would have produced one of Shakespeare's plays.

But of course. Shakespeare produced Shakespeare's plays.

Precisely. And how probable was Shakespeare?

We need not settle this here, which is as well, because we're not going to. My point is that evolution

could

proceed from design. Of course we already know that: we're already doing gene splicing and other experiments with DNA. Add to that some of the discoveries we've made about electric eels and think how we might improve upon them; stir together into a mixture containing old and new civilizations; recall that many people know little about their own history; and you have the ingredients for a whacking good story. Edward Hughes has done just that.