Impossible: The Case Against Lee Harvey Oswald (26 page)

Read Impossible: The Case Against Lee Harvey Oswald Online

Authors: Barry Krusch

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

In addition to this “escape clause” for the primary conjecture, the HSCA stated that the nature of the conspiracy they were considering was in any event functionally identical to the lone assassin scenario:

House Select Committee on Assassinations Final Report, Page 98

“If the conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy was limited to Oswald and a second gunman, its main societal significance may be in the realization that agencies of the U.S. Government inadequately investigated the possibility of such a conspiracy. In terms of its implications for government and society, an assassination as a consequence of a conspiracy composed solely of Oswald and a small number of persons, possibly only one, and possibly a person akin to Oswald in temperament and ideology, would not have been fundamentally different from an assassination by Oswald alone.”

Based on the preponderance of data identified above, the two government documents and two primary lone assassin books, I conclude that the statement

There was one and only one gunman in Dealey Plaza, who was not aided and abetted by anyone.

is the first proposition in The Case Against Lee Harvey Oswald.

At first glance, the idea that there was

one and only one

assassin of the President would seem to be a tangential consideration in assessing the guilt of Oswald. After all, couldn’t Oswald have been the assassin who shot President Kennedy even if there were multiple shooters?

Perhaps, but then again,

perhaps not

, and if it can be shown that the first proposition cannot be demonstrated true beyond a reasonable doubt, the validity of the second proposition is

automatically

thrown into doubt! Of the severest possible kind! How can

Proposition Two

(“Lee Harvey Oswald was the

lone

gunman in Dealey Plaza on November 22, 1963”) possibly be true if there was

more than one

gunman?!

Vincent Bugliosi was well aware of the consequences for the case if

Proposition One

was demonstrated to be, from the legal perspective, false. In

Reclaiming History

, regarding the mock trial he conducted with Gerry Spence in London in 1986, Bugliosi related the reason he had to hammer home the point that Oswald was the lone assassin, and in the relation of that reason showed why the death of

Proposition One

would

automatically

lead to the death of the

entire case

(RH Endnotes, p. 553; emphasis supplied):

[I]f the jury believed or suspected that others were involved, this would inevitably generate in their minds a number of unanswered questions

about who these people were and the nature of their involvement. These thoughts in turn could cause the jurors to conclude that they simply did not know the whole story, what really happened,

hurting the credibility of my whole case

against Oswald

and

raising a reasonable doubt

of his guilt

in their minds.

Read that well: if others

were

involved in the assassination of Kennedy, “reasonable doubt” as to the guilt of Oswald would

automatically

be raised in the minds of the jurors!

Bugliosi re-related the point yet again in a separate context in his book (RH 833; emphasis supplied):

A few Dealey Plaza witnesses gave statements of observing men on the upper floors of the Book Depository Building, which, if true, would support the conclusion that whoever shot Kennedy from the building may have had someone else with him. Since this would conflict 100 percent with the Warren Commission’s conclusion of no conspiracy,

it arguably spills over and throws into question the Commission’s main conclusion that Oswald killed Kennedy, and I am therefore including this discussion under the “evidence of Oswald’s innocence” rubric.

Read that well: if there

was

a conspiracy to kill Kennedy, it would throw into question the Commission’s main conclusion, so much so that it should be considered evidence of Oswald’s innocence!

These twin admissions by Bugliosi are absolutely key: if anyone would know how devastating the existence of a conspiracy would be to the primary conclusion, it would be a prosecutor with decades of experience, twenty of them studying the Kennedy assassination.

As Bugliosi has noted, the

mere evidence

of conspiracy

itself

raises reasonable doubt, particularly in light of the fact that the commission found

no evidence

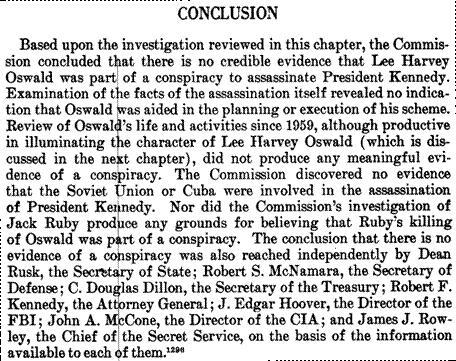

that Oswald was tied to a conspiracy (WR 374):

In other words, if there

was

a conspiracy, according to the Warren Commission, we must assume Oswald was

not a part of it

! So in and of itself, curiously enough, the prosecution’s case does indeed rest on what first glance appears to be an unrelated proposition.

This point is so critical, let’s analyze it further to see why conspiracy automatically creates doubt.

Remember the final conclusion to be established: “Lee Harvey Oswald fired the shot that killed President John F. Kennedy.” Note that the crime is:

murder

of a President

but not

shooting at a President and

missing

nor

shooting at a President and

wounding

without killing

So, if there

was

a conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy, to prove the conclusion that “Lee Harvey Oswald fired the shot that killed President John F. Kennedy,” it would

not only

be necessary to show that Oswald was one of the shooters, but it would

also

be necessary to show that Oswald fired the

fatal

shot, which would automatically be assumed if he was the only gunman, but would be extremely difficult to show if he was not. This is because only

one

of the three shots claimed to be fired that day in Dealey Plaza by the Warren Commission was a fatal shot — the bullet which struck Kennedy in the back was not fatal, and one bullet

missed completely

. It was only the headshot which resulted in the death of President Kennedy.

Therefore, if Oswald

did

fire a shot, and there were multiple shooters, perhaps Oswald fired the shot that missed, and

only

that shot, which would mean obviously that he did not fire the shot that killed President Kennedy.

So, from a probability perspective, even if Oswald

did

fire a shot, there would be a 66% probability that he did not fire the shot that killed the President, and if he fired two shots, a 33% chance, which in both cases falls well short of the reasonable doubt standard.

Of course, if the evidence ultimately showed that

more

than three shots were fired, then the probability would drop even more.

In the face of this argument against the main conclusion, some would argue that the

vicarious liability

rule in criminal law would result in Oswald’s guilt. As Bugliosi himself noted (RH Endnotes 552),

Oswald’s defense attorneys wouldn’t argue . . . that Oswald was a part of a conspiracy, because if they did, under the vicarious liability rule of conspiracy (which makes each conspirator criminally responsible for all crimes committed by his co-conspirators in the furtherance of the object of the conspiracy), they would be arguing Oswald’s guilt.

There are at least two points to note about Bugliosi’s observation: if Oswald

was

part of a conspiracy (as a murderer or one aiding and/or abetting a murder), he would indeed be guilty from the perspective of vicarious liability, but the conclusion of the Warren Commission and every other entity that advocates the

Lone Assassin Theory

is

not

that Oswald was guilty from a vicarious liability perspective, but that he

actually

fired the shot that killed the President!

And so, therefore, there is a further point, far more critical. Oswald’s attorneys would not necessarily argue that Oswald was a part of a conspiracy, as Bugliosi claims. To the contrary, what they would more likely have argued was that there

was

a conspiracy of which Oswald was

not

a part!

1

Unfortunately for the vicarious liability theory, Oswald’s

motivation

must also be factored in, for the purpose of establishing what in criminal law is known as

mens rea

(Latin for “guilty mind”

2

); in other words,

intent

.

Without the proper

intent

to commit the crime, Oswald could not be found guilty of that crime.

3

This is one of the most elemental principles in criminal law, and Oswald’s defense could have rested on this necessary principle. As Jessica Kozlov-Davis wrote in the

Michigan Law Review

,

4

Most commentators agree that the

mens rea

for conspiracy is purpose, or a specific desire to further the criminal enterprise. No federal statute explicitly prescribes a

mens rea

for conspiracy. The Supreme Court has consistently held that, based on the Model Penal Code,

the appropriate

mens rea

is intent to further the aims of the conspiracy

. According to the Model Penal Code, a person is guilty of conspiracy if, with the purpose of promoting the commission of a crime, he agrees with another person to engage in such conduct as constitutes a crime, or agrees to help another person plan or commit a crime.

The prosecution must meet two burdens in a conspiracy case. First, it must establish that the defendant knew of the unlawful goals of the conspiracy. Second, it must establish that the defendant had the purpose or intent to further its goals, and thus intended to be member of the conspiracy.

In the

Creighton Law Review

, Ryan Grace additionally noted that there were

two

types of intent required to establish conspiracy, “intent to

achieve the objective

of the conspiracy, and “intent to

agree to commit

a conspiracy.”

5

Considering that the Warren Commission found no evidence that Oswald had any intent to agree to commit a conspiracy,

that evidence simply does not exist

, and so any vicarious liability theory must fall.

Other books

Her Last Breath: A Kate Burkholder Novel by Linda Castillo

Pursuit of a Parcel by Patricia Wentworth

The Belgariad 5: Enchanter's End Game by David Eddings

Fat Off Sex and Violence by McKenzie, Shane

The Man Who Wasn't There: Investigations into the Strange New Science of the Self by Ananthaswamy, Anil

Blind Mission: A Thrilling Espionage Novel by Schmidt, Avichai

The Dinosaur Chronicles by Erhardt, Joseph

Mask - A Stepbrother Romance by Daire, Caitlin

Borrowed Billionaire #3 Return to Mr. Thorne by Mimi Strong

Believing by Wendy Corsi Staub