In Amazonia (3 page)

Authors: Hugh Raffles

A particular inspiration has been the convergence of two recent

bodies of work: one that seeks to reconfigure the logic of the modern (to dissolve nature/culture binaries, for example) and one that excavates the ontologies of Renaissance nature.

10

Communing with the latter no longer means taking facts, to use Mary Poovey's helpful term, as “deracinated particulars.” Nor does it require relying on the opposition of the particular (the Aristotelian “historical”) to the universal (the “philosophical”), nor on the hierarchized division of labor between natural history and natural philosophy that this distinction underwrote. Modern facts, including “natural” facts, contain and speak from theoryâa position that natural historians eventually came to acknowledge.

11

But there are many ways through which the thickness of facts can be accomplished. With its resistance to regularities and its emphasis on “diversity more than uniformity, and the breaking of classificatory boundaries more than the rigors of taxonomy,”

12

pre-Baconian natural history persists as a reminder of the dynamic and unsettled variety of modes of knowing, a trace of other ways of imagining, experiencing, and investigating nature.

Reading back into earlier natural histories, I have reimagined this book as a collectionâalthough one committed (so far as writing allows) to keeping its objects alive and in motion. Unlike the collection of the nineteenth century, in which “the object is detached from all its

original functions in order to enter into the closest conceivable relation to things of the same kind,”

13

this is an ecumenical assemblage for which I have gathered, cared for, arranged, and displayed small pieces of a world of difference breathing life into the husks of their connections, finding new meanings and possibilities through juxtaposition. Yet, as with Henry Walter Bates' Amazonian collection, mine too is marked by incompleteness as much as wholeness. And it is held fast in various elsewheres by the attachments that objects, however violated in their recontextualization, retain to place and biography. A collection is a work of affinity, intensity, and excess, “a form of practical memory” that binds us skin to skin with the richly real.

14

Describing his own collecting of books, Benjamin noted that “every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector's passion borders on the chaos of memories.”

15

The chaos of memories from which I draw this book is one of identifications and seductions. It is not only the natures that hold me. I like the people here too much as well.

When I first took up this project, I pictured it forming around a more familiar politics of agency and restitution: the story of anthropogenesis in the space of wilderness. As I have already indicated, some of that story remains. But I was hijacked, and the book followed. Now it feels closer to the real, all entanglements, cross-talking, and open ends. And now it has to begin again, this time with the remains of a trauma that shadows every page.

A few short years ago, two of my sisters, still young, died suddenly and unexpectedly and within just fifteen weeks of each other. Twice, 3,000 miles away in New York City, I answered the phone.

In an instant

, twice, I learned that when such things happen (things that are both unbearably particular and profoundly universal) nothing that will happen or has happened is ever the same. New lines appear, cleaving the lives of all who survive. At such times of crisis, affect has a materiality so overwhelming that nothing else matters. Crisis, I found, crushes time and space, exploding their assumptions, until scaleâthe very ordering logic of everyday life and the most comfortable of accommodationsâbecomes a visceral and destabilizing problem, no longer convincing as ideological fantasy (“structuring our social reality itself”).

16

At such moments of ontological and epistemological excess, everyday coordinates are suspended and the world is experienced as if everything were up for grabs.

Within a few months of these deaths, I found myself, as if shell-shocked,

washed up on the banks of the Rio Guariba, introverted and self-absorbed, miserable, and inflicting my misery on those unlucky enough to be my hosts. With my growing understanding that the

extremis

of sudden loss was a familiar condition here, the encounterâas should be evidentâdeveloped a happier and more encompassing intensity. But the arbitrariness and particularity of fieldwork could not have been more apparent. The peculiar optic through which I discovered Amazonia, my hypersensitivity to the affective, to the purposive politics of trust and complicity, to the inconstancies of time and place, to a world of dense and dynamic materialities, all thisâthough now fading fast in the face of life's relentless normalityâhas overdetermined, structured, shaped, and textured this project. Its mark is indelible. It seeps through cracks, forcing them open, forcing remembrance.

I last visited Amazonia in 1999. Not long before leaving, I spent a few days in the logging town of Paragominas with Moacyr, whom I introduce more fully in

Chapter 6

. He was showing me how, even though the timber industry has moved west from there, its traces linger, as material as can be: mills disused and giant heaps of sawdust abandoned in the midst of flimsy wooden housing. The piles smolder, threatening to ignite, but children play on them anyway, now and again sliding down through the shifting surfaces, badly burning their bodies.

It was a hot afternoon and we crisscrossed the sprawling town, thirsty, walking up and down, far and wide. At one pointâwe were talking about foreign researchersâMoacyr asked me how it was that foreigners could come here, get to know maybe one or two places, perhaps a couple more if they stayed a long time, and then return to their universities, stand in front of roomfuls of students, and teach about somewhere they called Amazonia. What, he asked, with a mixture of bafflement, irony, and refusal, allows them to make such a claim: to pretend that they know

Amazonia?

Despite his then strained circumstances, there was no animus in Moacyr's question. It was, rather, a grappling out loud with the profound asymmetries that allowed his life to be so easily circumscribed. It was a struggling that had come to reside in a particular, cosmopolitan sense of wonder, a marveling that this complicated world of condensed and generative intimacies could be so contained by language, travel, and science. That it could be collected and displayed as if nothing were lost in translation.

2

DISSOLUTION OF THE ELEMENTS

The Floodplain, 11,000 BPâ2002

Where Do Correct Ideas Come From?âThe EvidentiaryâThe Canal de Igarapé-MiriâTerra AnfÃbiaâBiographical Politicsâ“Those Days of Slavery Were Really Hard”âTravels on the ArapiunsâRivers of HungerâA Chimerical LandscapeâThe VaradoresâPrecisions of Language and Practices of SpeechâA Typology of ChannelsâA Chance MeetingâThe GenealogicalâWhat Remains of Cultural Ecology?âA New Ancient HistoryâEnvironmental Possibilism and Historical EcologyâPractices of IntimacyâAmapá and the Textures of Fluvial InterventionâThe Wood-Road and the DredgerâThe Pleasures of TaxonomyâAnother Order of Fluidity

“Where do correct ideas come from?” Mao Zedong asked his revolutionary cadres in May 1963. “Do they drop from the skies? ⦠Are they innate in the mind?” Many certainties collapsed in the second half of the twentieth century, but Mao's answer is still entirely unimpeachable. “They come from social practice,” he states without equivocation, “and from it alone.”

1

What do we know about Amazonians and Amazonian nature? There are two closely related ways of knowing, both of which arise in and are themselves practices. One is evidentiary, one genealogical. Let's begin with the evidence.

T

HE

C

ANAL DE

I

GARAPÃ-

M

IRI

I was reading a crumbling pocket edition of

Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro

, Alfred Russel Wallace's account of his tragic journey to Brazil.

2

It was Wallace's first trip outside England, four unhappy years during which he lost a beloved brother to yellow fever and an entire collection of specimens and drawings to a catastrophic shipboard fire that left him drifting ten days in mid-Atlantic. Finally back in Britain, he published his

Travels

to an indifferent response. The book is flat, despite its adventures, cobbled together from letters, the few notebooks that survived, and a disconsolate memory. Darwin, in an uncharitable moment, wrote: “I was a

little

disappointed in Wallace's book on the Amazon, hardly facts enough.”

3

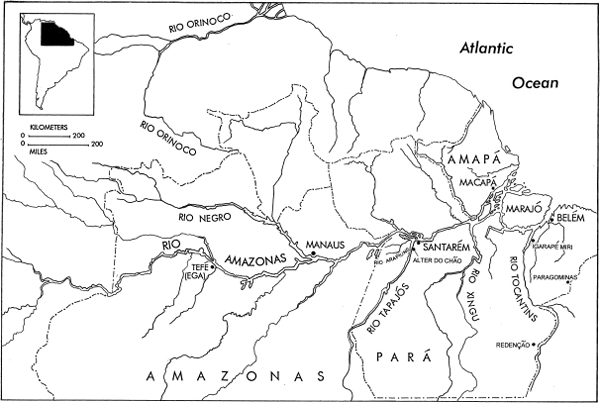

Map showing places mentioned in this book

Darwin and Wallace's relationship was too intimate for innocent criticism, of course.

4

Not only would they compete for ownership of the theory of natural selection, but Wallace, a complicated maverick who paid the professional and personal price for unorthodoxy, would finally depend on Darwin to petition Prime Minister Gladstone for the pension that would keep him one step from destitution.

5

In August 1848, though, he was still an ambitious young autodidact from the artisan class. It was a paragraph in the second chapter that caught my eye. I must have read it before more than once without pausing, but this time canals were on my mind. Wallace is describing a boat journey from the state capital Belém to the Rio Tocantins:

At nine

A.M.

, on the 28th we entered the Igarapé MirÃ, which is a cut made for about half a mile, connecting the Mojú river with a stream flowing into the TocantÃns, nearly opposite Cametá; thus forming an inner passage, safer than the navigation by the Pará river, where vessels are at times exposed to a heavy swell and violent gales, and where there are rocky shoals, very dangerous for the small canoes by which the Cametá trade is principally carried on. When about halfway through, we found the tide running against us, and the water very shallow, and were obliged to wait, fastening the canoe to a tree. In a short time the rope by which we were moored broke, and we were drifted broadside down the stream, and should have been upset by coming against a shoal, but were luckily able to turn into a bay where the water was still. On getting out of the canal we sailed and rowed along a winding river, often completely walled in with a luxuriant vegetation of trees and climbing plants.

6

The perils of the journey are clear enough, but the character of the “cut” is ambiguous. Wallace had arrived in the Amazon just three months earlier, and he was sailing with his close friend Henry Walter Bates. After frustrating delays in Belém, the two naturalists had eagerly accepted an invitation from Charles Leavens, a Canadian timber merchant,

to join him as he scoured the unmapped upper Tocantins for valuable “cedar.” It was on the outward leg of this expedition that the party passed through Igarapé-Miri. Soon after, unable to contract guides or porters, Leavens cut short the proposed three-month trip and within five weeks of departing they were all back in the city, somewhat deflated. Bates, unfailingly scrupulous, records the same journeyâthough marking it for the next dayâand describes the waterway unequivocally as “a short, artificial canal.”

7

Such a tame spot for two explorers to almost lose their lives. A popular shipping route, in fact. And, as you might expect, it turned out that Wallace and Bates were by no means the only published authors to pass through the canal at Igarapé-Miri. Trawling nineteenth-century travel writing, a literature of chorography and social commentary, I found that the radical railroad engineer and poet Ignácio Baptista de Moura had been here too.

Baptista de Moura's account is quite different from either Wallace's or Bates'. Local political economy had gone through some drastic changes in fifty years. But isn't it also because of his connection to the fledgling Socialist Workers' Party of Pará that, where the British naturalists marveled at walls of luxuriant vegetation, Baptista de Moura looked from the deck of his boat to see a desolate scene of barely functioning sugar mills lining the banks of the canal?

8

In the 1840s, Atlantic steam transport had been introduced, boosting the internal export markets in the south of Brazil. The competitive advantage gained by the sugar planters of the Brazilian northeast had more or less wiped out the Amazon trade in white and brown sugar and cane-honey. The factories Baptista de Moura described in 1896, their original water- or animal-powered motors often replaced by British steam engines, were scraping by, distilling

cachaça

, white rum, for the local market.

9