In Amazonia (33 page)

Authors: Hugh Raffles

Back in the days when Miguelinho was still a schoolboy and the vila was the economic heart of his grandpa's community, each household had its own notebook in which the store clerk kept a running transactional account. The book entries were coupons, replacements for

money and accepted only in Viega's store. They were the means of controlling exchange that represented the accumulating debt of the freguesesâin the red from the moment they received the goods with which to build their first house. Benedito Macedo, José's father and an old man himself now, laughs as he tells me how he likes to think of all that uncollected debt totaled neatly but pointlessly in those columns when Raimundo died. But then, changing register, he points out that, unlike other families who allowed Viega to keep their books in his store, the Macedos insisted on holding theirs at home so they would always know the state of their finances.

Members of the Viega familyâMiguelinho, Sônia, and the wealthier relatives now living in Macapáâtoday unanimously diminish the coercive significance of historical debt, emphasizing instead the virtues of paternalism and the positive lubricating role of patrão-dependent credit networks in easing the flow of goods. Seu Benedito, in contrast, talks about the success of his family in managing the pitfalls of cash-poverty through those times: never taking more goods than they knew their resources could cover, always frugal and conservative, always within their narrow means, refusing to succumb to the temptations of cane liquor, positioning themselves for the hour independence would be within their grasp. As a negative exemplar, Seu Benedito describes his old friend Pedro Preto, drinking away his hard labor and now living hand-to-mouth, without even fishing nets of his own.

But, inevitably, debt is ambiguous even for the Macedos. José Macedo is a hard-working man with a large family who worries continuously about the future of Igarapé Guariba. When he and his father look at Sônia, they see a moral continuity with the old patrão in her erosion of community integrity, most shamefully in the seductive use of cane liquor to enforce relations of indebtedness. Yet they, too, run a small front-porch store, and they, too, sell alcohol, though almost clandestinely and only for consumption off-premises. Moreover, their public discourse echoes the one Nestor Viega and his siblings attribute to their papai: to advance merchandise on credit is to help neighbors through the bad times. There is some agile reconciling afoot. Sônia's credit is a destructive force in the community; theirs is a cohering mutual aid.

For most families in Igarapé Guariba today, as in the time of Viega, a degree of indebtedness is a necessary part of life and an expression of a dependency that is likely to cease only with the social relationship of which it is partâwith death or other disaster. Many people now spread

their debt and proliferate their dependencies, building independent clientalist relations with merchants (and politicians) in Macapá in a way that was impossible while the monopoly on credit was held by Old Man Viega.

The Macedos do the same, but their networks replicate the hierarchies forged by Raimundo Viega in a manner distinct from that of their own neighbor-fregueses in Igarapé Guariba. For the other families in this community, debt relations are a creative practice through which they can sustain economic and social alternatives outside the structures imposed by the Macedos. For the Macedos themselves, the resources captured through patronage relations are what enable them to maintain their local authority in Igarapé Guariba. It is all about rivers again. All about maneuver and negotiation in a space that is simultaneously compressed by the geographic logic of the riverine community and exploded by the expansiveness of fluvial travel.

A

ÃAÃ

The intimate, politics-saturated relations through which debt is realized in Igarapé Guariba are just part of a series, an extensive set of traveling iterations. Those boats on which I huddled in the early morning sunshine were most often making the four-hour trip along the Amazon to Macapá. And, for six months of the year, they'd be laden down with açaÃ, the most valuable forest commodity available. The açaà trade brings together those things I am trying to make sense of here: Amazon rivers, the politics of space, and the work of historical intimacies. I want to follow it to and from Igarapé Guariba, and back and forth between the Viegas and Macedos. But we should begin in Macapá.

The streets close to the docks in Macapá are lined with small stores selling general goods to people from the interior. The shopowners who trade there generally act as patrões to a number of rural fregueses, advancing goods on monthly credit, “discounting” their merchandise against forest products brought in on the boats. Although the relationships are most commonly expressed in the vocabulary of clientalism (patrão and freguês), these are the persisting structures of aviamento, and the storekeepers act as minor

aviadores

, their clients as

aviados

. In turn, these patrões become fregueses in relation to the larger urban wholesalers who stock their stores, and, when they get back to the interior,

the fregueses (such as José Macedo) who visit the stores in Macapá may become patrões to the local collectors who supply them with forest products such as açaÃ. Nestor Viega explained it for me:

You have the guy who's in charge down here. That's how it starts. Then he has his patrão. Just as he's the patrão here, he has another one over there, and the other one has another one still. It's a scale, you understand? So, for example, he goes to his patrão ⦠well, papai didn't actually have to go to Belém, he'd send a letter: “Look, I need such-and-such goods, I'm going to send you such-and-such in return: bananas, rubber, etc. and I need such-and-such. I'm paying the bill, so you send me some more stuff.” What he meant was, “I'm going to use your goods. I'm going to supply my freguês. My freguês is going to pay me. I'll pay you. The guy over here's going to pay what's-his-name over there, and so on.

Of course, it requires a certain cultural capital to create effective clientalist relationships in the first place. Not just anyone can do it, and the ability to do so both marks and generates prestige. One afternoon in Guariba, I found myself in the middle of an argument. My friend Dora's father in Macapá had just decorated their house for his youngest daughter's

quinze anos

party with 800 balloons. Dora's husband was scathing: “Tio Paulo's a fool throwing away all his savings on this,” he was shouting as I walked in. But Dora had a stronger grasp of cultural economy: “It didn't cost him one

centavo

,” she snapped back, quick as a whip. “He got it all on credit.”

Tio Paulo, in fact, was well known in Macapá. Nowadays, he is more or less retired. But he had done many kinds of work over the years and for a while had even tried his hand as an açaà distributor. But that wasn't the kind of work that suited him, getting up at all hours to hang round the docks and bully incoming traders into selling him their fruit. Instead, he would periodically supplement his pension by sailing off to stay with his two daughters in Igarapé Guariba, working on the boats, earning a pittance, but bringing back fish to sell to his relatives and açaà for the dockside buyerâ“

tirando o boi

,” making ends meet, as Benedito Macedo, José's father and Paulo's longtime friend, put it.

Distributing açaà could have been a lucrative line of work. Minor fortunes have been made since the industry took off in the past few years, and conversations with people in the trade suggest there are

about 25,000 people in Macapá and the surrounding floodplain earning their living from it for at least part of the year.

26

Açaà is the fruit of the

açaizeiro

, a slender, graceful palm that can always be found growing around houses on the estuarine floodplain. Traveling on the rivers, you spot the distinctive trees first and then the wooden houses tucked away underneath. Farmers manage açaà in a complex and sophisticated manner, thinning its multiple clumps, removing senescent individuals, building up the soil to prevent waterlogging, manipulating the crown architecture, clearing around the base to remove competitors and make sure there are no hidden animals to surprise children and teenagers shimmying up to harvest the fruit.

27

After three or four years, the palm begins producing heavy bunches of dark, grape-sized fruit with a thin pulp surrounding a fibrous seed. After about eight years it reaches a peak, continuing to bear fruit for a further ten.

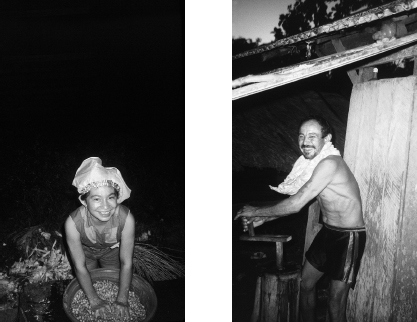

Rosiane and Braga strike a pose as they prepare the evening's açaÃ.

People in the interior soak and mash the fruit, and mix it with river water to make a purple liquid. This used to be an afternoon task for women and girls, who worked it through sieves by hand. Now, many households have a wooden, hand-powered juicer, and men and teenage boys take turns working the soaked fruit. When it comes time to eat, everyone thickens their bowl with manioc meal orâif more middle-class and living in the cityâoften with tapioca, eating the result either with or without sugar.

28

Açaà is a definitively rural food and, while in season, an indispensable part of the day's largest meal, served alongside fresh fried fish, salty boiled shrimp, or forest game. Yet, it has been the estuarine cities of Belém and Macapá that have driven the recent market. As people have left the often chaotic countryside for the service-deficient, violent, but alluring peri-urban slums that ring the more affluent centers, they have brought their taste for açaà with them and they've sparked shifts in the diet of an urban middle-class prone to ruralist nostalgia.

29

By midday on almost every streetcorner in Macapá, you see a 5-foot pole with a 6-inch rectangular red metal flagâthe sign that the açaà seller is ready to begin the lunchtime trade.

I never met a retailer in Macapá reluctant to tell the hard-luck story of declining profits and intensifying competition. Just a couple of years ago, it seems, you might go three or four blocks before finding a stall, but now they're everywhere. Back then, a seller might juice four sacks of fruit a day.

30

Now he or she has to settle for one and a half. At the same time, high demand and the marketing stranglehold of the big suppliers have pushed up the price, and low-income urban workers might drink açaà only every few days at best.

To capture local trade the retailers sell to their customers on credit, but then they have to deal with lack of cash and the headaches at the end of the month when the time to call in debts comes round. The competition is killing them. In Macapá they all agreed that this was a function of the combination of two factors: the sudden deep freeze into which the job market had been plunged by President Fernando Henrique Cardoso's 1994

Plano Real

currency stabilization, and the rapid influx of work-hungry people from the interior and the northeast of Brazil in response to the empty promise of Macapá's

zona franca

, the free-trade area legislated in the early 1990s.

31

Most açaà businesses are set up through suppliers, capitalized entrepreneurs who arrange contracts with both urban retailers and rural

transporters, and who exercise considerable control over the market. The suppliers collect fruit from the boats as it comes in from the interior, and they distribute it in town. They could be called

atravessadores

, those who pass something on, middlemen, but they balk at the term, reserving it for the smaller operators they see scavenging the docks and disrupting business through gangster tacticsâpressuring the boatmen and showing no concern for long-term trading conditions. These larger-scale suppliers see themselves rather differently and prefer the more polished term

fornecedores

. They are the açaà elite who foster paternalist relations with rural suppliers and urban retailersâhelping them through difficult times, disciplining them by manipulating pricing and restricting supply, maneuvering to marginalize their atravessador rivals.

The supplier who takes most of the Macedo brothers' açaà is Jacaré, an easy-going, unaffected man in his mid-50s, who never touches açaà himself: “It's a drug,” he says, only half-joking. “Look at my son, he's addicted!” Jacaré has bought açaà from José Macedo for nine years now, and it was José who gave me his phone number and told me to look him up next time I was in Macapá.

Jacaré's strongly vertically integrated operation accounts for 10 percent of the thousand sacks of açaà that enter the city daily from the interior of Amapá, and he distributes to fregueses beyond Macapá in towns all around the state. He sets people up as retailers on either a profit-sharing or a rental basis. And any agreement with him includes a commitment to buy his fruit.

Despite the small margins and the discourse of dissatisfaction, it is clear why so many people are entering the retail end of the trade.

32

With the national minimum wage set at R $112 a month for those able to find work, açaà is a compellingly dynamic and relatively accessible sector of the regional economy. Yet, access always depends on some form of capital: a potential retailer needs both cash and the cultural capital earned through participation in networks of patronage and alliance, the type of business that Nestor Viega acutely calls “a family thing.”