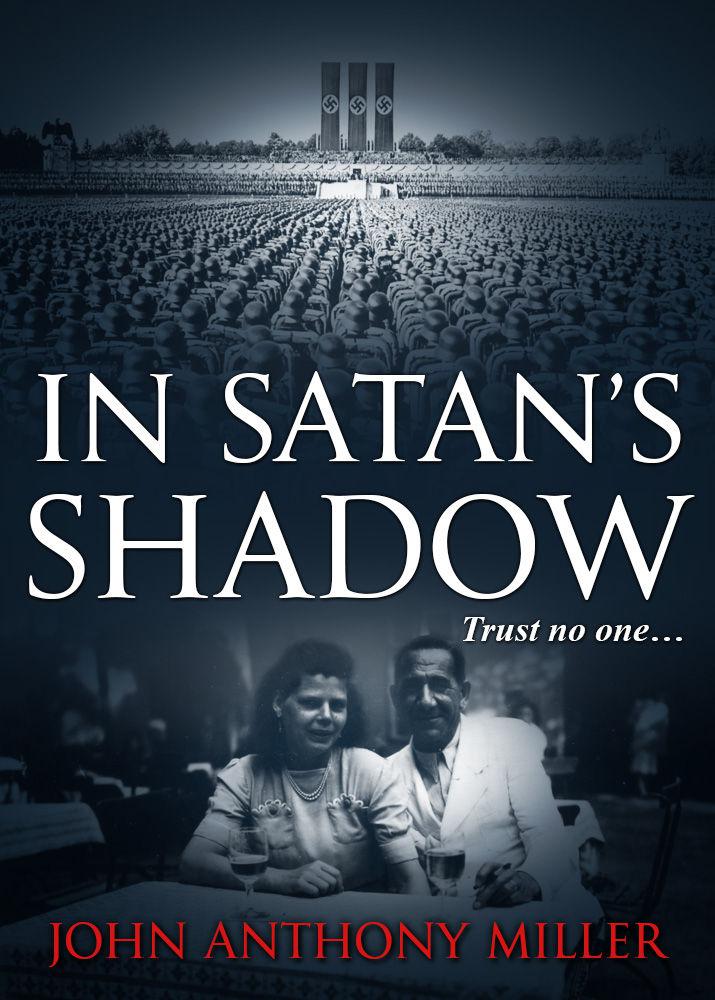

In Satan's Shadow

Authors: John Anthony Miller

© John Anthony Miller 2016

John Anthony Miller has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

First published by Endeavour Press Ltd in 2016.

London, England

November 26, 1946

London was alive with optimism after the war ended: ruins in renovation, the hurt healing, the separated reunited, and the dead honored and mourned. The future offered so much more promise than the past, when two global conflicts in a generation left tens of millions dead, and many living who wished they were not. But hundreds, if not thousands, of Nazi leaders responsible for the recent cataclysm had vanished, eluding the net cast by the Americans, Russians, British, and French. It was feared they assembled in an unknown country and continent, birthing the Fourth Reich on the ashes of the Third.

Michael York stood in the Victorian Treasures book store, gazing at a display of recent releases. His face was solemn, his eyes showing a muted pain, as he looked at the week’s bestseller. It was a book of photographs, Berlin in the last decade, as night fell and darkness draped the world.

From the store front window he could see Tower Bridge, the Thames winding underneath it. A double-decker bus stopped, blocking his view, and two Canadian soldiers got off, followed by some schoolchildren. The bus drove away, revealing an American soldier in a red telephone booth, probably calling his British girlfriend. London was inundated with military personnel savoring a last look at the greatest city in the world before they returned home. Most were American, buoyant and brash but friendly, while others represented the British Empire: Canadians, South Africans, Australians, and some from the Caribbean. They wandered the streets, the world theirs for the taking, savoring every pleasure the global metropolis had to offer.

He opened the book, turning to the dust jacket, and studied the author’s picture. It was a good photograph, capturing the twinkle that lived in her eye, a smile that came so easily to her face, and wavy black hair that cascaded upon her shoulders. Amanda Hamilton, born to Scottish royalty, had married a German, a leader in the Nazi party. Leaving her homeland behind, she spent ten years in Berlin, absorbing a new culture, starting a new life. Her photographs documented a world collapsing around her, civilization at its ebb, humanity at its worst. Now they were shared with mankind.

Michael York turned the pages, her pictures bringing the past to life, memories returning. Germany’s evil geniuses were caught in poses the world had never before seen. Berlin’s finest buildings: Kaiser Wilhelm Church, the Reichstag, the Berlin Cathedral, and the Brandenburg Gate were shown in their original splendor, before Allied bombs destroyed them. And birds, not knowing they had trespassed on a calamity, posed innocently but proudly.

Fate had placed her on the enemy’s doorstep, friend to some of the most hated men on earth during the most tumultuous days in human history. A favorite of Hitler, admired by Goebbels and Göring, her photographs documented life in the upper echelons of the Nazi party, a world that none on earth ever dreamed existed. It was there that Amanda Hamilton, never the author of an evil thought, walked in Satan’s shadow.

Ferrette, France - near the Swiss border

September 30, 1942

The bullet had done much damage. Piercing his chest and tearing the muscles of his shoulder, it left a large, gaping hole in his back as it exited his body. Blood flowed freely, staining his shirt and dripping lazily on the dirt below.

Michael York lay beneath a rocky outcrop, his body wracked with pain. He stared vacantly at the half moon, listening intently. A hundred meters behind him, spread along the trees that rimmed the hill, twenty German soldiers approached.

“Leave me,” he whispered. “Save yourselves while you still can. I may not be able to make it.”

“We cannot,” Jacques insisted. He was young and short and muscular, a farmer no one suspected of aiding the British.

“You’re too important, my friend,” said Michelle, the farmer’s wife. “That’s why the Germans are so persistent.” Tall and slender to compliment her stocky husband, they had been rescuing downed airmen for months. York was their first spy.

“How bad is it?” York asked.

Michelle pressed a kerchief against his chest. “We have to stop the bleeding. And then just two more kilometers and you’ll be safe in Switzerland.”

York ignored the pain. He heard the Germans calling out to each other, looking for him, fanning out on the hillside, searching. Some moved farther away. Others came closer.

He tried to move, his muscles weak. He shivered, even though the night was pleasant, the weather warm.

“Quiet!” Jacques hissed. “They are coming.”

Two Germans walked towards them, sticking bayonets in shrubs. They were talking, pausing to study the hillside, watching the rocks, looking for movement. One soldier approached, the other observed, vigilant, his rifle ready.

York, Jacques, and Michelle crouched under the ledge. They could hear the German’s boot slipping in the soil, dirt and pebbles sliding past them. Then he stood just above them.

Jacques withdrew his knife. He moved against the rock, crouching, prepared to attack.

A black boot descended, less than a meter away, and then gray trousers. The German faced away from them, tentatively maneuvering down the hill. Soon both legs were visible, and then his torso.

When his entire body emerged, Jacques crept forward, his knife drawn. Using one hand to cover the surprised soldier’s mouth, he drove the knife in his back, near the kidney. Pulling the German towards him, he withdrew the blade and slit his throat.

Jacques pulled the soldier under the overhang. He lay there gasping, dying, blood seeping from his body and blotting the soil.

Seconds passed silently. Jacques crouched near the edge, hidden from view. York and Michelle lay in the cleft, huddled together, barely breathing.

“Hans?” the second German called. “Hans?”

Jacques waited, knife in hand.

They heard the second German approach. When the barrel of his rifle peeked past them, Jacques grabbed it and pulled. The German tumbled over the edge, landing on his back. Jacques pounced on him, thrusting the knife in his chest. He pulled the body under the overhang.

“We have to keep moving,” he said coldly, his face pale.

Michelle and York climbed out of the alcove and started down the hill, struggling with the incline, their shoes slipping in the soil.

Jacques looked over his shoulder. “Quickly,” he said. “The others will be looking for them.”

As York continued on, hunched and humbled, slipping and sliding, he felt his strength waning. Jacques and Michelle stayed beside him, propping him up, moving him forward, trying to stem the flow of blood.

“At the base of the hill, we’ll cross the dirt lane and enter the woods,” Michelle said. “There’s a clearing past the trees; the Swiss border is just beyond it.”

They moved down the hill, stumbling, trampling wildflowers that sprinkled the landscape, leaving an easy path for the enemy to follow. But it didn’t matter. They only had to beat them to the border.

York was amazed at Michelle’s strength. She held him upright, supporting him, enabling him to walk as quickly as she did. Jacques stood behind them, guarding, watching over his shoulder.

They slid the rest of the way down the slope to the road, finding a narrow gully beside it. They looked over their shoulders, up the hillside. The soldiers had reached the overhang above them, finding their dead companions.

“Hurry,” Jacques said. “Into the woods before they see us.”

They were interrupted by a vehicle in the distance, gears shifting. Headlights cast a soft glow on the lane, then off into the woods as it negotiated a bend, and back to the road.

Jacques held up his hand. “Wait until the lights aren’t shining on us.”

The vehicle came closer. The road wound, the headlights moved, but instead of pointing into the trees, they twisted at an odd angle, briefly shining on York, Michelle and Jacques before turning away.

The Germans saw them and scrambled down the hillside, shouting. A shot was fired, the bullet creating a plume of dirt less than a meter away.

“Stay low,” Jacques said, guiding them forward.

They crossed the road, hunched over, moving swiftly, knowing they were now most vulnerable. More shots were fired, bullets peppering the road, pinging off rocks, imbedding in trees.

The vehicle sped forward, closing the distance, as they made their way into the woods. They angled to the right rather than forward, staying parallel to the road just a few feet into the woods, avoiding the shortest route to the border to confuse their pursuers.

The vehicle, a German panel truck, the Nazi symbol on the sides, stopped where they had entered the woods. Two soldiers got out and stood in the road, watching, waiting for those coming down the hill.

The soldiers reached the road in groups of two and three, talking frantically to the driver and his companion. Some pointed to the woods; others faced the hill, describing the pursuit. A few minutes later the rear doors of the truck opened. Dogs started barking.

“There’s a stream just ahead,” Michelle hissed as they shared alarmed glances. “The dogs will lose the scent in the water.”

They kept moving, struggling in the dark but still making progress. They had the advantage of knowing the terrain. The enemy didn’t.

The dogs barked loudly, the noise constant. But as minutes passed, the sound grew dimmer.

“The Germans are forcing the dogs forward,” Jacques said. “They don’t believe we’re near the road. They think we’re trying to reach the border.”

Michelle frowned. “But that won’t last long. So we must hurry.”

They continued onward, pushing through the underbrush. At times it was dense, and they had to cut through it, and often it was sparse, more like a clearing. After three or four minutes passed, they noticed a change in the dogs’ barking. It was getting louder, coming towards them.

“We’re almost at the stream,” Michelle said. “How are you doing, York?”

“I’ll make it,” he said, his teeth clenched. But he wasn’t so sure.

Fifteen meters more and they reached the stream. It was knee-deep, ten meters wide, and twisted away from the road. They stepped in, walking with the current, making rapid progress.

The dogs were moving quickly, having picked up the scent, and were coming closer. They could hear soldiers shouting to each other as they fanned across the forest, slowly starting to encircle them.

“The stream has a fork just ahead,” Michelle said. “Left goes to the border. Right moves parallel with the road. We’ll go right for a half kilometer and then east, crossing the farm fields into Switzerland.”

The German voices were louder, but the sound of barking dogs grew fainter. They had divided their forces. Some crossed the stream with the dogs, moving east, assuming the shortest route to the border was taken. The others, those whose voices could be heard, were coming closer, moving south, trying to flank them.

Michelle’s plan was succeeding. Using the stream and alternate paths, they were eluding the Germans. But they were no closer to the border.

York was gasping for air, the loss of blood making him weaker. His legs felt like lead, but he plodded forward, knowing each step took him closer to safety.

They sloshed through water until they could no longer hear soldiers or dogs, then they left the stream, moved through more forest, and reached a clearing. It was a farmer’s field, the edges marked by hedges. Rows of thigh-high wheat stretched before them.

“There’s a road at the edge of the field, where that far hedge is,” Michelle said, pointing. “It’s bordered by a stone wall, not impassable, a meter high at most. The fence marks the border.”

York stared ahead and summoned his remaining strength. He reached to his breast pocket and felt the faded photograph he always carried with him, next to his heart. He could make it. He was sure of it.

“How far after that?” he asked.

“There’s a safe house a kilometer up the road,” Jacques said. “We’ll take you there.”

“And we’ll get a doctor,” Michelle added.

They left the trees, knowing they were exposed, and started through the field. They crouched low, maintaining the smallest possible profile, moving quickly. Michelle and Jacques flanked York, propping him up, sometimes dragging him.

There were no dogs, no Germans; they seemed safe. They walked across the field, each step taken bringing safety and security. They had almost reached the hedges, only twenty meters more, when York glanced over his shoulder.

He saw the tiny light far in the distance. It was orange, an ember, not even a flame. Like someone inhaling a cigarette.

Using all the strength he had remaining, he shoved Jacques and Michelle to the ground. The sharp report of a machine gun sounded a second later.

York felt the biting sting of a bullet in his left thigh. It was followed by another, and then another, as the gunner raked his leg with bullets.