In Search of Goliathus Hercules

Read In Search of Goliathus Hercules Online

Authors: Jennifer Angus

For my son, Sasa &

my father, William H. Angus

&

In memory of my mother, Anne W. Angus 1932–2002

Special thanks to Robert Apholz

1890

H

enri sat by the window in Great Aunt Georgie’s old, creaky house, gazing out to the pasture through the falling rain. All was quiet beyond the sound of the pitter-patter of raindrops and a fly’s annoying buzz as it made futile attempts to gain its freedom by breaking the window’s glass barrier. Stupid fly! thought Henri.

Henri

is French for Henry. It is pronounced “On-

ree

.” Henri thought it was inexplicable that his parents named him that. Neither of them spoke French, nor did he seem to be named after a distant relative. Everyone who knew him pronounced his name “Henry,” but those who didn’t often asked, “

Parlezvous français

?”

Henri lived in the country on Woodland Farm with his Great Aunt Georgie, his father’s aunt. It wasn’t a working farm anymore. There was a house, a cheery two-story redbrick building that the ivy was threatening to disguise completely. The fields had lain fallow for years and the barn was empty. In short, the farm seemed to have fallen on hard times.

Despite the lack of activity, there were lots of places to explore—particularly down by the creek—and there were many good places to build forts. The problem was, there was no one Henri’s age to lay siege to his fort. The only person he had to converse with was Great Aunt Georgie, whose primary interest in life was collecting buttons. Most of her conversation centered around buttons, which meant that their discussions were fairly one-sided since Henri didn’t know anything about them. A typical exchange at dinner went like this:

“Henri, did you know that the earliest button was found five-thousand years ago?”

“No, I didn’t.”

“Did you know that buttons were first used to fasten clothing in Germany in the thirteenth century?”

“No. But if that’s true, what did they use them for before then?” asked Henri, perplexed.

And so on and so on. Henri feigned polite interest, knowing that if he did not appear to be somewhat attentive, there would be little to discuss beyond the weather.

To Henri, Great Aunt Georgie looked like she must be a hundred years old. Whether she was or not, Henri would never know for sure because he knew it was impolite to ask a woman’s age.

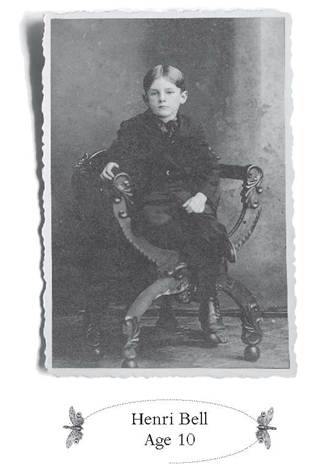

Now, many would expect an English boy with the name Henri to stand out or be remarkable in some way, but there was nothing in particular to distinguish him. He was just under five feet tall. He had brown eyes and brown hair that he parted in the middle. He didn’t have any scars, although he wished that he had because there’s always a good story that goes with a scar. Really, not very much had happened to him—just one thing: he was sent alone without his mother or father to live with ancient Great Aunt Georgie three thousand miles from home.

Prior to the long steamship voyage to America, he had lived with his mother in a small flat in London. It was just the two of them because Henri’s father had departed nearly three years before to take up a position as a superintendent on a rubber plantation with the British East India Company in Malaya. Looking in an atlas, Henri discovered that Malaya was a tropical country, south of Siam, and nearly halfway around the world! Henri had to close his eyes and concentrate very hard to picture his father’s face. It had been so long since there had been any news from him.

Henri gazed out the window and watched the raindrops hit the already-formed puddles. The fly continued to buzz in frustration at its inability to penetrate the window glass. Henri recalled happy memories of his father. His most cherished was his seventh birthday outing just before his father had left for Malaya. The family had gone to the zoo. They spent most of their time in the Asian pavilion because Henri’s father wanted to show him the animals that were native to Malaya.

Henri had admired the sleek, majestic tigers that padded about their cage, ever watchful, as if waiting to pounce. Huge saltwater crocodiles blinked their eyes from time to time, which was the only way you could tell they were alive so still did they lie. When asked what his favorite animal was, Henri responded, “Elephants.” One of the few postcards that Henri received from his father in Malaya showed a grand procession of elephants through a village.

Now he pulled a ragged stack of postcards tied with string out of his pocket. On top was a yellowed newspaper page, folded neatly, that Henri had kept because he had found an article entitled “Tiger Tales” about wildlife in the Malay jungle. He removed it from the pile and put it aside. He picked up the elephant postcard and turned it over. He didn’t need to read it—he could recite it from memory. Anyway, it didn’t say anything more than one expected from a postcard. It contained the usual sentiments such as “love you” and “wish you were here.”

Henri turned back to the window. The rain seemed to be slowing down. The fly continued to buzz against the glass, looking for a way out. From time to time it stopped and, for lack of a better word, fidgeted. If a fly had hands, it would be scrubbing them together. It was a greedy type of movement, as if it were about to swoop down upon something particularly tasty. If Henri was to do that at the dinner table in front of a meal of roast beef, potatoes, and green beans, Great Aunt Georgie would surely rap his knuckles. Great Aunt Georgie was a devoted reader of

Beadle’s Book of Etiquette

and often quoted passages she felt were relevant to Henri’s proper upbringing. Salivating and “carrying on” were definitely considered bad manners.

He watched the fly as it continued to buzz about, stopping from time to time to fidget. The constant buzzing and scrubbing was annoying.

Finally Henri said out loud, “Could you stop that?”

From below on the windowsill came a faint sound, not buzzing. Henri would later realize it was a chuckle.

He looked down and there was another fly, but this one was quiet, not buzzing, nor scrubbing…It was moving quickly back and forth across the newspaper page Henri had set on the sill. Henri moved closer. Could it be? The fly appeared to be reading the newspaper!

“You know it’s rude to read over someone’s shoulder,” said the fly.

“Sorry!” said Henri, greatly taken aback. Had he heard that right? In an effort to get the fly to speak again, he said, “Excuse me, I hope you don’t mind if I ask, but…are you actually reading?”

“Yes, I do mind,” said the fly. “Don’t you think it would be proper if we introduced ourselves first?”

“Oh, I’m sorry,” said Henri. “I am Henri Bell, and I am Great Aunt Georgie’s nephew.”

“Yes, I know. She mentioned you,” said the fly.

“She mentioned me!” exclaimed Henri. “You talk to Aunt Georgie?!”

“Yes, of course. She is the owner of this house, and I am a housefly, after all.”

“Oh, um…” How could he respond to that? “Um, you didn’t mention your name.”

“I am

Musca domestica

, but you may call me Dom,” said the fly.

“I am very pleased to meet you,” said Henri, and he actually meant it. Dom was the only person—or rather, thing—that he had spoken to since he had arrived at the house. Other than Great Aunt Georgie and her very unfriendly neighbor, the widow Black. The latter didn’t count since she had spoken the entire time, not even allowing him a word in edgewise.