In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind (45 page)

Read In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind Online

Authors: Eric R. Kandel

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Cognitive Psychology

As a first step toward solving the easy problem of consciousness, we need to ask whether the unity of consciousness—a unity thought to be achieved by neural systems that mediate selective attention—is localized in one or just a few sites, which would enable us to manipulate them biologically. The answer to this question is by no means clear. Gerald Edelman, a leading theoretician on the brain and consciousness, has argued effectively that the neural machinery for the unity of consciousness is likely to be widely distributed throughout the cortex and thalamus. As a result, Edelman asserts, it is unlikely that we will be able to find consciousness through a simple set of neural correlates. Crick and Koch, on the other hand, believe that the unity of consciousness will have direct neural correlates because they most likely involve a specific set of neurons with specific molecular or neuroanatomical signatures. The neural correlates, they argue, probably require only a small set of neurons acting as a searchlight: the spotlight of attention. The initial task, they argue, is to locate within the brain that small set of neurons whose activity correlates best with the unity of conscious experience and then to determine the neural circuits to which they belong.

How are we to find this small population of nerve cells that could mediate the unity of consciousness? What criteria must they meet? In Crick and Koch’s last paper (which Crick was still correcting on his way to the hospital a few hours before he died, on July 28, 2004), they focused on the claustrum, a sheet of brain tissue that is located below the cerebral cortex, as the site that mediates unity of experience. Little is known about the claustrum except that it connects to and exchanges information with almost all of the sensory and motor regions of the cortex as well as the amygdala, which plays an important role in emotion. Crick and Koch compare the claustrum to the conductor of an orchestra. Indeed, the neuroanatomical connections of the claustrum meet the requirements of a conductor; it can bind together and coordinate the various brain regions necessary for the unity of conscious awareness.

The idea that obsessed Crick at the end of his life—that the claustrum is the spotlight of attention, the site that binds the various components of any percept together—is the last in a series of important ideas he advanced. Crick’s enormous contributions to biology (the double helical structure of DNA, the nature of the genetic code, the discovery of messenger RNA, the mechanisms of translating messenger RNA into the amino acid sequence of a protein, and the legitimizing of the biology of consciousness) put him in a class with Copernicus, Newton, Darwin, and Einstein. Yet his intense, lifelong focus on science, on the life of mind, is something he shares with many in the scientific community, and that obsession is symbolic of science at its best. The cognitive psychologist Vilayanur Ramachandran, a friend and colleague of Crick’s, described Crick’s focus on the claustrum during his last weeks:

Three weeks prior to his death I visited him in his home in La Jolla. He was eighty-eight, had terminal cancer, was in pain, and was on chemotherapy; yet he had obviously been working away nonstop on his latest project. His very large desk—occupying half the room—was covered by articles, correspondence, envelopes, recent issues of

Nature

, a laptop (despite his dislike of computers), and recent books on neuroanatomy. During the whole two hours that I was there, there was no mention of his illness—only a flight of ideas on the neural basis of consciousness. He was especially interested in a tiny structure called the claustrum which, he felt, had been largely ignored by mainstream pundits. As I was leaving he said: “Rama, I think the secret of consciousness lies in the claustrum—don’t you? Why else would this tiny structure be connected to so many areas in the brain?”—And gave me a sly, conspiratorial wink. It was the last time I saw him.

Since so little is known about the claustrum, Crick continued, he wanted to start an institute to focus on its function. In particular, he wanted to determine whether the claustrum is switched on when unconscious, subliminal perception of a given stimulus by a person’s sensory organs turns into a conscious percept.

ONE EXAMPLE OF SUCH SWITCHING THAT INTRIGUED CRICK AND

Koch is binocular rivalry. Here, two different images—say, vertical stripes and horizontal stripes—are presented to a person simultaneously in such a way that each eye sees only one set of stripes. The person may combine the two images and report seeing a plaid, but more commonly the person will see first one image, then the next, with horizontal and vertical stripes alternating back and forth spontaneously.

Using MRI, Eric Lumer and his colleagues at University College, London have identified the frontal and parietal areas of the cortex as the regions of the brain that become active when a person’s conscious attention switches from one image to another. These two regions have a special role in focusing conscious attention on objects in space. In turn, the prefrontal and posterior parietal regions of the cortex seem to relay the decision regarding which image is to be enhanced to the visual system, which then brings the image into consciousness. Indeed, people with damage to the prefrontal cortex have difficulty switching from one image to the other in situations of binocular rivalry. Crick and Koch might argue that the frontal and parietal areas of the cortex are recruited by the claustrum, which switches attention from one eye to the other and unifies the image presented to conscious awareness by each eye.

As these arguments make clear, consciousness remains an enormous problem. But through the efforts of Edelman on the one hand, and Crick and Koch on the other, we now have two specific and testable theories worthy of exploration.

AS SOMEONE INTERESTED IN PSYCHOANALYSIS, I WANTED TO TAKE

the Crick-Koch paradigm of comparing unconscious and conscious perception of the same stimulus to the next step: determining how visual perception becomes endowed with emotion. Unlike simple visual perception, emotionally charged visual perception is likely to differ between individuals. Therefore, a further question is, How and where are unconscious emotional perceptions processed?

Amit Etkin, a bold and creative M.D.-Ph.D. student, and I undertook a study in collaboration with Joy Hirsch, a brain imager at Columbia, in which we induced conscious and unconscious perceptions of emotional stimuli. Our approach paralleled in the emotional sphere that of Crick and Koch in the cognitive sphere. We explored how normal people respond consciously and unconsciously to pictures of people with a clearly neutral expression or an expression of fear on their faces. The pictures were provided by Peter Ekman at the University of California, San Francisco.

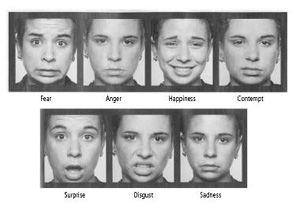

Ekman, who has cataloged more than 100,000 human expressions, was able to show, as did Charles Darwin before him, that irrespective of sex or culture, conscious perceptions of seven facial expressions—happiness, fear, disgust, contempt, anger, surprise, and sadness—have virtually the same meaning to everyone (figure 28–1). We therefore argued that fearful faces should elicit a similar response from the healthy young medical and graduate student volunteers in our study, regardless of whether they perceived the stimulus consciously or unconsciously. We produced a conscious perception of fear by presenting the fearful faces for a long period, so people had time to reflect on them. We produced unconscious perception of fear by presenting the same faces so rapidly that the volunteers were unable to report which type of expression they had seen. Indeed, they were not even sure they had seen a face!

28–1

Ekman’s seven universal facial expressions. (Courtesy of Paul Ekman.)

Since even normal people differ in their sensitivity to a threat, we gave all of the volunteers a questionnaire designed to measure background anxiety. In contrast to the momentary anxiety most people feel in a new situation, background anxiety reflects an enduring baseline trait.

Not surprisingly, when we showed the volunteers pictures of faces with fearful expressions, we found prominent activity in the amygdala, the structure deep in the brain that mediates fear. What was surprising was that conscious and unconscious stimuli affected different regions of the amygdala, and they did so to differing degrees in different people, depending on their baseline anxiety.

Unconscious perception of fearful faces activated the basolateral nucleus. In people, as in mice, this area of the amygdala receives most of the incoming sensory information and is the primary means by which the amygdala communicates with the cortex. Activation of the basolateral nucleus by unconscious perception of fearful faces occurred in direct proportion to a person’s background anxiety: the higher the measure of background anxiety, the greater the person’s response. People with low background anxiety had no response at all. Conscious perception of fearful faces, in contrast, activated the dorsal region of the amygdala, which contains the central nucleus, and it did so regardless of a person’s background anxiety. The central nucleus of the amygdala sends information to regions of the brain that are part of the autonomic nervous system—concerned with arousal and defensive responses. In sum, unconsciously perceived threats disproportionately affect people with high background anxiety, whereas consciously perceived threats activate the fight-or-flight response in all volunteers.

We also found that unconscious and conscious perception of fearful faces activates different neural networks outside the amygdala. Here again, the networks activated by unconsciously perceived threats were recruited only by the anxious volunteers. Surprisingly, even unconscious perception recruits participation of regions within the cerebral cortex.

Thus viewing frightening stimuli activates two different brain systems, one that involves conscious, presumably top-down attention and one that involves unconscious, bottom-up attention, or vigilance, much as a signal of salience does in explicit and implicit memory in

Aplysia

and in the mouse.

These are fascinating results. First, they show that in the realm of emotion, as in the realm of perception, a stimulus can be perceived both unconsciously and consciously. They also support Crick and Koch’s idea that in perception, distinct areas of the brain are correlated with conscious and unconscious awareness of a stimulus. Second, these studies confirm biologically the importance of the psychoanalytic idea of unconscious emotion. They suggest that the effects of anxiety are exerted most dramatically in the brain when the stimulus is left to the imagination rather than when it is perceived consciously. Once the image of a frightened face is confronted consciously, even anxious people can accurately appraise whether it truly poses a threat.

A century after Freud suggested that psychopathology arises from conflict occurring on an unconscious level and that it can be regulated if the source of the conflict is confronted consciously, our imaging studies suggest ways in which such conflicting processes may be mediated in the brain. Moreover, the discovery of a correlation between volunteers’ background anxiety and their unconscious neural processes validates biologically the Freudian idea that unconscious mental processes are part of the brain’s system of information processing. While Freud’s ideas have existed for more than one hundred years, no previous brain-imaging study had tried to account for how differences in people’s behavior and interpretations of the world arise from differences in how they unconsciously process emotion. The finding that unconscious perception of fear lights up the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala in direct proportion to a person’s baseline anxiety provides a biological marker for diagnosing an anxiety state and for evaluating the efficacy of various drugs and forms of psychotherapy.

In discerning a correlation between the activity of a neural circuit and the unconscious and conscious perception of a threat, we are beginning to delineate the neural correlate of an emotion—fear. That description might well lead us to a scientific explanation of consciously perceived fear. It might give us an approximation of how neural events give rise to a mental event that enters our awareness. Thus, a half century after I left psychoanalysis for the biology of mind, the new biology of mind is getting ready to tackle some of the issues central to psychoanalysis and consciousness.

One such issue is the nature of free will. Given Freud’s discovery of psychic determinism—the fact that much of our cognitive and affective life is unconscious—what is left for personal choice, for freedom of action?

A critical set of experiments on this question was carried out in 1983 by Benjamin Libet at the University of California, San Francisco. Libet used as his starting point a discovery made by the German neuroscientist Hans Kornhuber. In his study, Kornhuber asked volunteers to move their right index finger. He then measured this voluntary movement with a strain gauge while at the same time recording the electrical activity of the brain by means of an electrode on the skull. After hundreds of trials, Kornhuber found that, invariably, each movement was preceded by a little blip in the electrical record from the brain, a spark of free will! He called this potential in the brain the “readiness potential” and found that it occurred 1 second before the voluntary movement.