In the Footsteps of Lewis and Clark (14 page)

Read In the Footsteps of Lewis and Clark Online

Authors: Wallace G. Lewis

Because of the nearly constant rainfall, everyone in Fort Clatsop became eager to leave the coastal range, even though they knew the high country of the Bitterroots would be impossible to cross before June because of the snowpack. On March 22, 1806, the expedition departed anyway, retracing its path up the Columbia. Moving past St. Helens, Oregon, and parallel to the route of Interstate 5, the party came upon a large river flowing from the south and entering the Columbia 142 miles upstream from its mouth, by Clark's reckoning. [VII, 66] They had missed the mouth of the Multnomah River on the outward journey because it was screened by a long island. From this point, on April 2 Clark reported that he was able to view the snowcapped volcanic peaks of Mount Rainier, Mount St. Helens, and Mount Adams in Washington and Mount Hood in Oregon. While

Lewis and the main body set up camp near present-day Washougal, Washington, Clark led six men to take a look at the Multnomah River. They encountered several villages of Chinookian-speaking people within the environs of Portland before returning to the main camp on the Columbia. For most of the rest of April the expedition repeated the portages of the previous fall around the Cascades and The Dalles. Tempers grew short as they dealt with the demands of, and thefts by, the Indian bands that controlled them. The captains were determined to cover much of the return route to the Nez Perce by land, but a dwindling supply of trade goods made it difficult to obtain horses.

On April 29, rather than continue up the Snake River, the Corps of Discovery struck out overland at the juncture of the Columbia and Walla Walla rivers, about thirty miles west of Walla Walla, Washington, to the Touchet River and through the sites of Prescott, Waitsburg, and Dayton, Washington. Lewis described the Touchet as “a bold Creek 10 yds. Wide,” its fertile bottom thick with cottonwood, birch, wild roses, and various berries, but the “surrounding plains,” he wrote, “are poor and sandy. The hills of the creek are generally abrupt and rocky.” [VII, 186â187] The nearly bare plain cut by tributaries flowing from the Blue Mountains to the south is now used primarily for dryland wheat farming. On May 3 they crossed the Tucannon River and proceeded along the valley of Pataha Creek to Pomeroy and down a steep gulch to the Snake River and its tributary, the Clearwater, west of Clarkston, Washington, and Lewiston, Idaho. They marched up the north bank of the stream they had floated down the previous fall, crossed it at the mouth of Potlatch (“Colter's”) Creek, then climbed up the south wall of the canyon downstream from the Canoe Camp site, on a rolling plateau called the Camas Prairie. This area south and west of the Clearwater River breaks is much like the Weippe Prairie from which the expedition had emerged the previous fall following the harrowing crossing of the Lolo Trail. Paralleling the main stem of the Clearwater, the party descended into the canyon by way of Lawyer Creek.

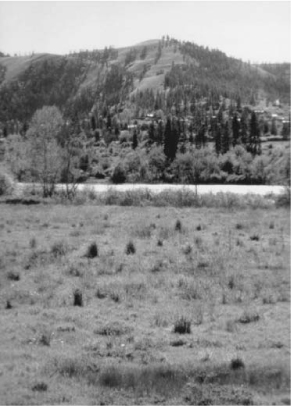

Just across the Clearwater from Kamiah, Idaho, they set up Long Camp, where they would stay while they rounded up the horses they had left with the Nez Perce and waited for the snow level to drop

in the towering Bitterroot Mountains to the east. In the meantime, Sergeant John Ordway led a small scouting expedition back west across the middle of the Camas Prairie to search for “Lewis's River,” the Snake River south of Lewiston, and to bring back salmon for provisions. Ordway's group left Long Camp on May 27 and crossed the route of Highway 95 between Craigmont and Ferdinand through Lawyer Creek Canyon, en route to Wild Goose Rapids on the Snake. On their return they skirted the Salmon River, which joins the Snake just a few miles south of Wild Goose Rapids. This was the river on which Clark had ventured downstream while looking for a way across Idaho from the Shoshone village near Salmon, Idaho. Ordway's men had taken just three days to reach the Snake River, but they needed another week to complete the reconnaissance and return to Kamiah by way of Cottonwood. They generally followed Cottonwood Creek, north of Grangeville, down to the South Fork (Clearwater) Canyon to Stites, then north to Kooskia and Long Camp across the Clearwater River from Kamiah.

In mid-June the Corps of Discovery, outfitted with supplies and horses, moved up out of Clearwater Canyon to the Weippe Prairie and the path the group had taken across the mountains in 1805. But on June 17 they had to turn back from “Hungery Creek” because snow banks still obscured the Lolo Trail. After obtaining the services of Nez Perce scouts, the group set out again. This time they easily made it along the ridges to Lolo Pass and down to the hot springs on Lolo Creek (“Traveler's Rest Creek”), where they bathed and relaxed on June 29. A day later they emerged from the shadows of the Bitterroot Range and rejoined the Bitterroot River at Traveler's Rest, where they split into two groups. Clark led the main body southward over Chief Joseph Pass into the Big Hole Valley and back down to Camp Fortunate, where the dugouts had been cached after the journey up the Missouri. Then the group retraced the outward-bound route down the Beaverhead and Jefferson rivers to the Three Forks.

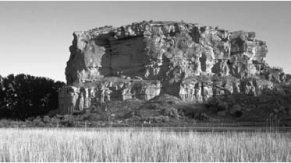

At the Three Forks Clark divided the men once again. Sergeant Ordway took one party down the Missouri River, northward, with the canoes. Clark and the remainder, including Sacagawea and her infant son, Jean Baptiste, went up the Gallatin River past the site of Bozeman, Montana, and over Bozeman Pass to the Yellowstone River at Livingston. At that point the Yellowstone River, flowing north from Yellowstone National Park, bends to the northeast. With difficulty, because they had insufficient horses and could find no adequate cottonwood trunks to make into dugouts, Clark's group worked its way down the Yellowstone past Big Timber and Columbus. On July 20, 1806, near Laurel, Montana, just east of Billings, they finally found trees suitable for canoes. A few days later the group came to an unusual and noticeable sandstone tower, upon which Clark carved his name and the date. He named it Pompey's Pillar, after the nickname he had bestowed on Jean Baptisteâ“Little Pomp.” They continued on in late July and early August past the future sites of Miles City, Fallon, and Glendive, Montana. On August 3 Clark's party camped at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers, where they planned to reunite with Lewis's group, which would be coming down the Missouri.

20

Fig 2.10

Vicinity of Long Camp, looking west across the Clearwater River to Kamiah, Idaho. Photo by Peg Owens. Courtesy, Idaho Department of Commerce.

Fig 2.11

William Clark's party, returning by way of the Yellowstone River in July 1806, came upon this monolith. Photo by Donnie Sexton. Courtesy, Travel Montana.

Back at Traveler's Rest, Meriwether Lewisâaccompanied by Drouillard, the brothers Joseph and Reuben Field, Sergeant Patrick Gass, and Privates William Werner and Robert Frazerâhad proceeded north a dozen or so miles along the Bitterroot River to the point where it empties into the Clark Fork River at Missoula, Montana. The men then turned east, passing through “Hellgate” gap from which the Clark Fork emerges. The Nez Perce scouts, who had left them at the confluence of the Blackfoot and Clark Fork rivers, had told the explorers that an easy overland shortcut would take them back to the

Great Falls of the Missouri along a long-used route to buffalo hunting grounds. The route was so widely traveled that they could not miss the path. Following the Blackfoot River Canyon northeast from Bonner, Montana, the party emerged into the broad Blackfoot Valley on June 7. A few miles east of Lincoln, the buffalo road cut north to Alice Creek, which headed on the Continental Divide. North of Rogers Pass, where Highway 200 crosses the Divide, Lewis's party reached a narrow saddle. Today it is known as Lewis and Clark Pass, although no roadway crosses over it. From the 7,452-foot elevation, the men could look out upon the prairies beyond the Great Falls. On the east side of the Divide they proceeded north to the Sun (“Medicine”) River near Augusta, which they followed due east to the White Island Camp south of Great Falls, the terminus of their portage route the previous July.

In the first of two strokes of good timing, Sergeant Gass's party, bringing the dugout canoes up the Missouri River, arrived at the same time. The second stroke of good timing occurred following a side trip Lewis, Drouillard, and the Field brothers made to explore the Marias River, which entered the Missouri downstream from Fort Benton. On July 16 the four men set out from the camp at the Great Falls north to the Marias River, which they followed upstream to Cut Bank Creek, passing the site of Cut Bank, Montana. On July 26 they stopped following the tributary at the location Lewis dubbed “Camp Disappointment,” since it was clear that the Marias River headwaters were not far to the north but rather in the near rampart of mountains, now part of Glacier National Park. After proceeding southwest to Two Medicine River (the Marias south fork), they encountered a group of Piegan Blackfoot warriors, who spent the night with them. In the morning Lewis and his men scuffled with the Piegans over a rifle and the horses. Two of the Blackfeet were killed. For the rest of the day and through the night, Lewis's party fled toward the Missouri River, knowing the Piegans would return in force. En route, they passed the site of Conrad, Montana. On July 28 the four men were enormously relieved to reach the bank of the Missouri just in time to meet Sergeant Gass's canoe party and be taken onboard.

On August 7, 1806, Lewis, Gass, and their men arrived at the junction of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers, just inside the present

North Dakota border. A message there told them that William Clark and the rest of the expedition had moved downstream after waiting a week. Lewis followed, hampered by discomfort from an accidental gunshot wound in the buttocks.

21

They caught up with Clark about thirty miles before reaching the mouth of the Little Missouri. The final leg of the journey, from Fort Mandan to St. Louis, went relatively quickly. What had taken the initial expedition party the entire summer of 1804, traveling upstream, passed by at a clip of nearly eighty miles per day when they were going downstream. By September 23 they were back in St. Louis.