In the Footsteps of Lewis and Clark (7 page)

Read In the Footsteps of Lewis and Clark Online

Authors: Wallace G. Lewis

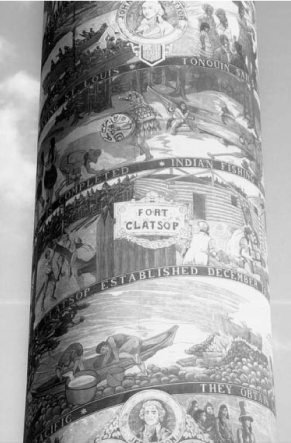

Along similar lines, the 1926 Astoria Column in Oregon incorporated a frieze depicting events of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and commemorating the explorers as major players in the conquest of the Pacific Northwest. Although not devoted entirely to Lewis and Clark (and not an example of heroic statuary), the Astoria Column stands out as the most grandiose monument to westward expansion in the Northwest and surely the most expensive historical site in the region prior to the nearby construction of a Fort Clatsop replica in the 1950s. This 123-foot-high cylinder, modeled to some extent on the second-century Trajan victory column in Rome, was erected on the crest of Coxcomb Hill, 640 feet above the Columbia River and the Astoria docks. The Great Northern Railway Company and descendants of John Jacob Astor, whose Pacific Fur Company had built the Astoria trading post in 1811, financed the structure to commemorate significant events in the history of Astoria and American expansion into Oregon country. Italian sculptor Attilio Pusterla was commissioned to create a frieze commemorating those events in a sequence of scenes spiraling from the bottom to the top of the column. Over the concrete surface, Pusterla put down layers of colored plaster depicting aspects of Chinook Indian life, Captain Robert Gray's discovery of the Columbia River, the arrival of Lewis and Clark in 1805, Wilson Price Hunt's overland expedition to help establish Fort Astoria, and other historic scenes. Visitors to the Astoria Column

could ascend an interior spiral staircase to the viewing platform at the top. The monument's dedication ceremony and the subsequent activities of dignitaries attending as participants in the Great Northern “expedition” indicate that Lewis and Clark were its principalâand heretofore largely forgottenâhonorees.

40

The dedication of the finished monument on July 22, 1926, presided over by Oregon governor Walter M. Pierce, featured speeches by historian Samuel Elliot Morrison of Harvard; Howard Elliot, chairman of the board of the Northern Pacific Railway; and Major General Hugh L. Scott of the U.S. War Departmentâ“a great authority on the American Indian.” A descendant of John Jacob Astor, Mrs. Richard Aldrich, replied. In his address, Morrison referred to Astoria as the “Plymouth Rock of the West,” having an older pedigree of European discovery even than New England.

41

General Scott spoke specifically about the exploits of the Corps of Discovery. The reputation of this “great American epic,” he said, “grows higher with time as it becomes better known and appreciated.” Scott noted that Sacagawea had been commemorated by two bronze statues but that Clark and Lewis had “been forgotten by the government they served so nobly.” Scott was unaware of any previous monuments to the two captains along the route except for a 1925 marker indicating the northernmost point Lewis reached during a probe up the Marias River in Montana. Now, through the “patriotic efforts of the Management of the Great northern Railway, which parallels their course for long distances,” that neglect was being corrected. Yet, he said, the “great Northwest . . . is itself their grandest monumentâmay it endure forever.”

42

The Columbia River Historical Expedition, headed by Ralph Budd, president of the Northern Pacific Railway, was the second of two company-sponsored “pilgrimages” to sites related to early explorationâthe Missouri Historical Expedition in the summer of 1925 and the foray the following year that climaxed with the dedication of the Astoria Column. According to Kammen, both expeditions did much to arouse public awareness of the West's historical heritageâalbeit in a triumphal vein that glorified conquestâand gave numerous historical societies along the routes “a shot in the arm.” Budd felt that far too much emphasis had been given to historical locations in the eastern United States and too little to those on the Trans-Mississippi Frontier, particularly in the northern portion and on the Lewis and Clark trail. Budd's special train carried a select group of observers, whose purpose was to study the historic areas through which the Great Northern and Northern Pacific lines ran and to dedicate various monuments and works. The 1925 expedition had visited sites in the Dakotas related to fur trade on the Missouri River, including Fort Union, near Williston, North Dakota, and the Bear Paw battleground in northern Montana where Chief Joseph's Nez Perce band surrendered to the U.S. Army in 1877. The 1926 Columbia River excursion went further, traveling west of Glacier Park through northern Idaho to Wishram, Washington, and thence along the Columbia to The Dalles, Portland, and Astoria, Oregon. There, the more than 150 “notables,” including Great Northern executives, took part in the dedication ceremony for the Astoria Column.

43

Fig 1.6

This 123-foot-high column on a hill overlooking Astoria, Oregon, and the Columbia River estuary was dedicated in 1926, with elaborate ceremony. It commemorates the arrival of Lewis and Clark and other important events in Astoria's history. Photo by Jeffrey Phillip Curry. Courtesy, Jeffrey Phillip Curry.

Fig 1.7

A close-up of the Astoria Column shows details of sculptor Attilio Pusterla's historic frieze, including the building of Fort Clatsop just a few miles west of Astoria, where the Corps of Discovery spent the winter of 1805â1806. Photo by Jeffrey Phillip Curry. Courtesy, Jeffrey Phillip Curry.

From Astoria, the group moved on to attend a ceremony dedicating a flagpole at what was believed to be the site of Fort Clatsop. An Astoria newspaper reported that “[t]hey are paricularly [

sic

] interested in [that] event and in the site of Old Fort Clatsop, wishing to tread the ground where the intrepid explorers passed their winter in the west.” From there it was on to Seaside, Oregon, “down to the end of the long, long trail of Lewis and Clark,” to dedicate improvements made around the Salt Cairn site.

44

There, during the winter of 1805â1806, a small detail had been assigned to boil seawater to obtain salt for preserving meat. The Salt Cairn site was originally marked by the Oregon Historical Society in 1900 “through the testimony of Jenny Mishel of Seaside, who was born in that vicinity in 1816 and died in 1905. Her Clatsop Indian father remembered seeing the white men boiling water at the site, and pointed out the place to her when she was a young girl.” The Great Northern paid to establish a “stonewall base, surrounded by an iron railing,” to replace the original “rustic” marker. A recreation of the actual cairn with its row of kettles was produced by the Seaside Lions Club in 1953.

45

North of the Cairn site, a sign and eventually a statue marked the end of the trail at the street turnaround in Seaside next to the Pacific Ocean beach. The designation was apparently made by the Oregon State Highway Commission.

46

Fig 1.8

In 1900 the Oregon Historical Society designated the Salt Cairn site at Seaside, Oregon, where a detachment of men from the Fort Clatsop winter quarters (1805â1806) boiled ocean water to make salt. Later, the Great Northern Railway Company provided a wall and an iron railing enclosure for the spot, now located just two blocks from the beach. In 1955 the Seaside Lions Club supplied the replica of a stone cairn and kettles. Photo by Jeffrey Phillip Curry. Courtesy, Jeffrey Phillip Curry.

Meanwhile, for decades the state of Montana unsuccessfully attempted to establish heroic statue monuments to the explorers, apparently beginning with a proposal around the time of the Portland exposition to place a statue at the site of Camp Fortunate, where the explorers met the Shoshone and bargained for horses, but nothing came of the original proposal.

47

In 1917 a bill introduced in the Montana Legislature called for heroic-sized bronze statues of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to be erected at Great Falls and at the Three Forks of the Missouri River. The measure, passed by both houses of the legislature, appropriated $5,000 but carried a stipulation that the Society of Montana Pioneers raise an additional $15,000 to help pay for the two statues.

48

The funds were not raised, and the proposal to create bronze figures lapsed.