In the Night of Time (86 page)

Read In the Night of Time Online

Authors: Antonio Munoz Molina

Â

IT GAVE ME A LITTLE START

of pleasure to see that face in the middle of a hostile city, a face tied to the sweetest memories of my hometown and childhood. When I was a boy, my mother often sent me to the door of Mateo Zapatón, who without knowing anything at all about me used to pat my cheek and call me Sacristan. “Mercy, Sacristan, this pair of half soles didn't last very long this time!” “Tell your mother I don't have change, Sacristan. She can pay me when she comes by.” The shop was very narrow and high-ceilinged, almost like a closet, and it opened directly onto the street by way of a glass door, which Mateo closed only on the most severe winter days. All the available space, including the sides of the chest he used as a worktable and counter, was covered with posters of bullfights and of Holy Week, the two passions of this master cobbler, glued-on posters, yellowed by the years, some pasted over others, announcements of corridas celebrated at the beginning of the century or at last year's fair, all in a confusion of names, places, and dates that fed Mateo's chatty erudition. He was almost always surrounded by his troop of friends, with a cigarette or tack between his lips, or both at once, a tireless narrator of historic anecdotes from the world of bulls and famous taurine maneuvers, which he knew at first hand because the presidents of the corridas often asked him to act as an official adviser. His voice would break and his eyes ill with tears when he was recalling the doleful afternoon when he watched from a row of seats on the sunny side of the bullring in Linares as the bull Islero charged Manolete. “He's going to hook you, don't get so close,” he had shouted from his seat, and he bent forward as if he were in the plaza and cupped his hands to make a megaphone, his face tragic with anticipation, living once again the instant when Manolete could still have saved himself from the fatal goring, “the fateful goring,” as Godino always said when he imitated the madly waving arms of the impassioned cobbler as he told that tale. Godino always promised some great and mysterious story about Mateo, a secret about which only he knew the most delicious details.

Â

I WENT UP TO MATEO

there in Chueca Plaza, and he looked at me with the same broad, benevolent smile he had worn when he welcomed the shoppers and the circle of friends who gathered at his cobbler's shop. I was moved to think that he recognized me despite how much I'd changed since the last time we saw each other. Just then another coincidence came to mind that linked him to my oldest memories and, without his knowing, made him a part of my childhood. In the space next to Mateo Zapatón's was the barbershop my father used to take me to, the one where my grandfather always got his haircut and shave, Pepe Morillo's shop, which was doing less and less business as his oldest customers died off and young people were letting their hair grow. Now his door was closed as tightly as Mateo Zapatón's and the Judas-face tailor's, like so many of the shops on Calle Real that once had been busy, before people gradually forgot to go by there, turning it, especially at night and on rainy days, into a ghostly, abandoned street. But in those days Pepe Morillo's barbershop was as animated as Mateo Zapatón's shoe repair, and often, on mild April and May afternoons, the clients of both shops would take chairs out on the sidewalk and smoke and talk in one single gathering, which was observed from the other side of the street, from the darkness of his empty shop, by the brooding tailor, who would wring his hands behind the counter and sink his head deeper between his shoulders, ever more closely resembling the Judas of the Last Supper, the misanthrope with the green face and hooked nose slowly pushed toward bankruptcy by the unremitting advance of mass-produced clothing.

My father, holding my hand, used to take me to Pepe Morillo's barbershop (back then “hair salon” was a woman's word), and I was so small that the barber had to put a little stool on the seat in order for me to see myself in the mirror and for him to be comfortable as he cut my hair. His face smelled of cologne and his breath of tobacco when he bent close with the comb and scissors, and he shaved my neck with a little electrical machine. I could hear his strong, fast breathing and feel the touch of capable adult fingers on the nape of my neck and on my cheeks, the rare pressure of hands that weren't those of my mother or father, familiar yet strange hands, suddenly brusque when he doubled my ears forward or made me bend way over by pushing the back of my head. Every time he trimmed my hair, almost at the end, Pepe Morillo would say, “Close your eyes tight,” and I knew he was going to trim the bangs to just above my eyebrows, cutting toward the middle of my forehead. Damp hair would fall on my eyelids, tickle my plump cheeks and tip of my nose, and the cold blades of the scissors would brush my eyebrows. When Pepe Morillo told me I could open my eyes now, I would be surprised by the round, unfamiliar face in the mirror, with protruding ears and straight bangs above the eyes, and also by my father's smile as he looked approvingly at my reflection.

I remembered all this as if I were reliving it when I unexpectedly ran into Mateo Zapatón in Chueca Plaza ... and something else that until that moment I hadn't known was in my memory. Once, as I was waiting my turn and reading a comic book my father had just bought for me, I felt thirsty and asked Pepe Morillo's permission to get a drink. He pointed to a small, dark interior patio at the rear of the barbershop, through a glass door and down a dark corridor. When you're a boy, the farthest places can be reached in only a few steps. As I pushed open the door, I think I was a little dizzy; maybe I was getting a fever and that was why I was so thirsty. The paving tiles were white and gray, with reddish flowers in the center, and they echoed as I walked across them. In a corner of the tiny patio, where a number of plants with large leaves added to the humidity, there was a pitcher on a shelf covered with a crocheted cloth, one of those clay water pitchers they had back then, a brightly colored, glazed jug in the shape of a rooster, made, I remember precisely, by potters on Calle Valencia. I took a drink, and the water had the consistency of broth and the taste of fever. I went back down the hallway, and suddenly I was lost. I wasn't at the barbershop but in a place it took some time to identify as the cobbler's shop, and the person I saw was the flesh-and-blood apostle Saint Matthew, although he was wearing a leather apron and not the tunic of a saint or a member of the brotherhood, and he was beardless, with the stub of an unlit cigarette in one corner of his mouth and a tack in the other. “Mercy, Sacristan, what in the world are you doing here? You gave me quite a turn.”

Â

JUST AS I HAD THEN,

I looked at Mateo and didn't know what to say. Up close he seemed much older, he no longer resembled the eternal Saint Matthew of the Last Supper. Neither his gaze nor his smile was directed at me: they stayed absolutely the same when I spoke his name and held out my hand to greet him, and when I clumsily and hastily told him who I was and tried to remind him of my parents' names and the nickname my family had back then. Limply holding my hand, he nodded and looked at me, although he didn't give the impression that he was focusing his eyes, which until a moment before had seemed observant and lively. His hat, more than tilted to one side, was skewed on his head, as if he had jammed it on at the last moment as he left the house or put it on with the carelessness of someone who can't see himself well in the mirror. I reminded him that my mother had always been a customer in his shopâthen shops had patrons, not customersâand that my father, who like him was also a great fan of the bulls, had often been present at his gatherings, and at those in Pepe Morillo's barbershop next door, which communicated with his via an interior patio. Mateo listened to those names of persons and places with the look of one who doesn't completely connect with things so far in the past. He bowed his head and smiled, although I also thought I noticed an expression of suspicion or alarm or disbelief in his face. Maybe he was afraid that I was going to cheat him, or assault him, like many of the thugs who hung around that areaâyou saw them all the time, kneeling in clusters beside the entrance to the metro and dealing in God knows what. I had to go, I was very late for an appointment that was probably futile in the first place, I hadn't had breakfast, my car was double-parked, and Mateo Zapatón was still holding my hand with distracted cordiality and smiling, his mouth half-open, his lower jaw dropped a little, with the gleam of saliva at the corners of his lips.

“You don't remember, maestro?” I asked him. “You always called me Sacristan.”

“Of course I do, man, yes,” he winked and stepped a little closer, and it was then I realized that now I was the taller. He put his other hand on my shoulder, as if in a benevolent attempt not to disappoint me. “Sacristan.”

But the word didn't seem to mean anything to him, though he kept repeating it, still holding the hand that now I wanted to get free, feeling trapped and nervous about continuing on my way. I pulled back but he didn't move, the hand with the soft, moist palm that had clutched mine still slightly raised, the hat with the tiny green feather twisted around on his forehead, standing there alone like a blind man, in the middle of the plaza, supported on the great pedestal of his large black shoes.

Visit

www.hmhco.com

or your favorite retailer to purchase the book in its entirety.

Â

Â

A

NTONIO

M

UÃOZ

M

OLINA

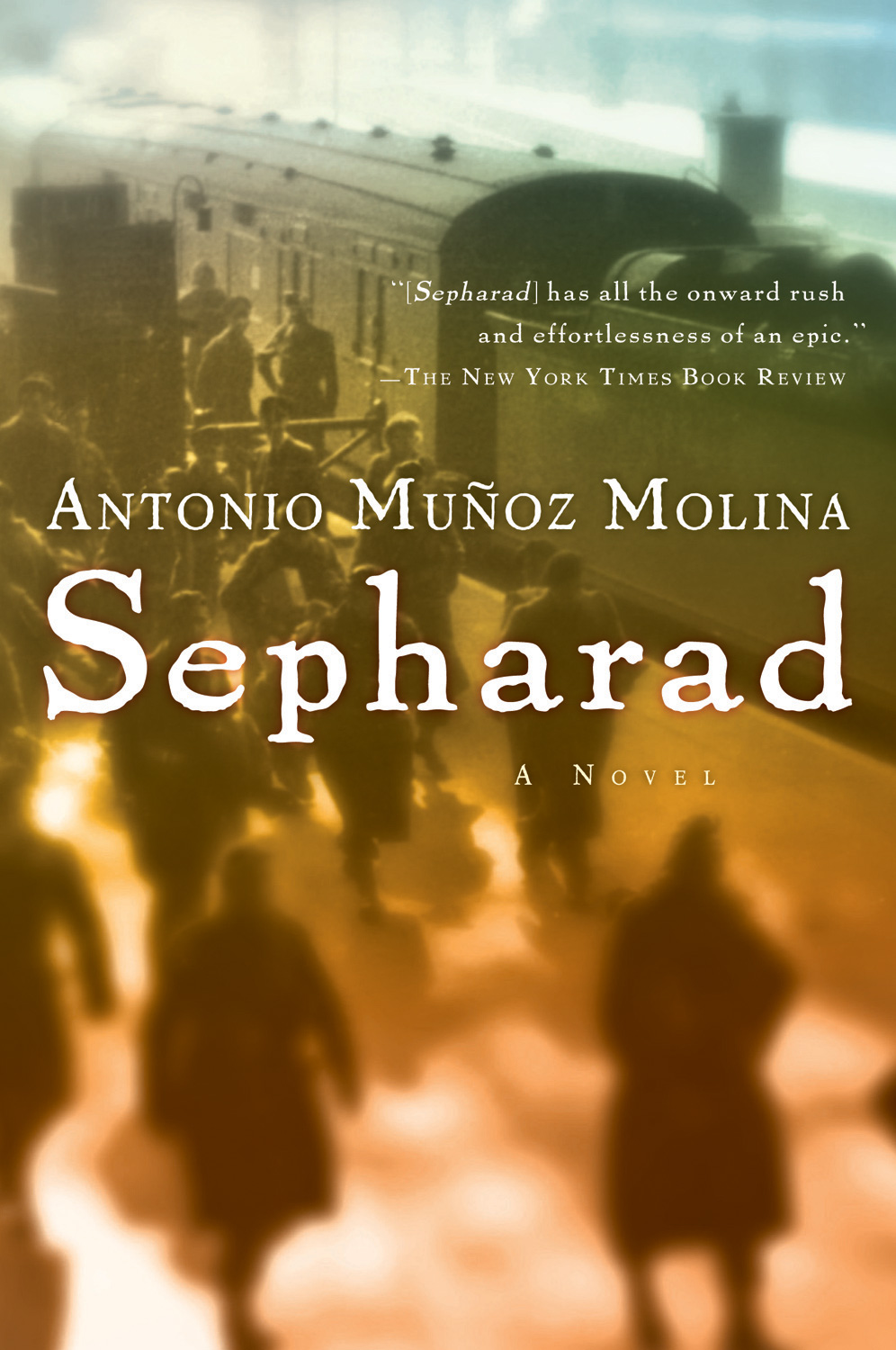

is the author of more than a dozen novels, among them

Sepharad, A Manuscript of Ashes,

and

In Her Absence.

He has also been awarded the Jerusalem Prize and the PrÃncipe de Asturias Prize, among many others. He lives in Madrid and New York City.

E

DITH

G

ROSSMAN

is the acclaimed translator of major Spanish-language authors, including Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez and Mario Vargas Llosa. She has received the PEN / Ralph Manheim Medal for translation and other honors.