In the Valley of the Kings

Read In the Valley of the Kings Online

Authors: Daniel Meyerson

Tags: #History, #General, #Ancient, #Egypt

ALSO BY DANIEL MEYERSON

The Linguist and the Emperor: Napoleon and

Champollion’s Quest to Decipher the Rosetta Stone

Blood and Splendor: The Lives of Five Tyrants, from

Nero to Saddam Hussein

For

PHILLIPE, (AL)CHEMIST EXTRAORDINAIRE

and

MUSTAFA KAMIL

I HAVE SEEN YESTERDAY. I KNOW TOMORROW.

—INSCRIPTION IN THE TOMB OF

PHARAOH TUTANKHAMUN, 1338 BC

CONTENTS

PART ONE

EXPENSES PAID AND NOTHING ELSE (BUT FATE)

PART TWO

NAKED UNDER AN UMBRELLA

PART THREE

THE WORLD OF NEBKHEPERURE HEKAIUNUSHEMA TUTANKHAMUN

PART FOUR

IN THE VALLEY OF THE KINGS

PART FIVE

A USEFUL MAN

PART SIX

A FINAL THROW OF THE DICE

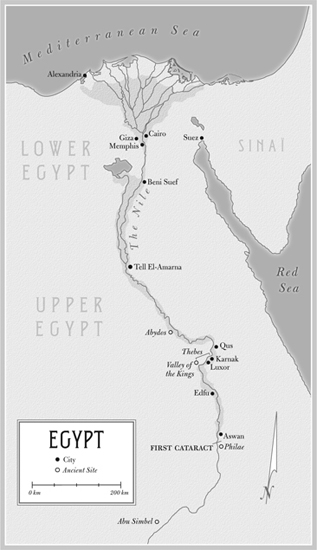

A NOTE ON THE MAP OF EGYPT

There are two sources for the Nile—one is in Uganda, the other in the Ethiopian highlands. The “two” Niles, the Blue Nile and the White Nile, join in the Sudan, at Khartoum, and begin their long journey toward the Mediterranean. When the Nile reaches Cairo, it fans out into many branches that run through a low-lying delta region to the sea. The area around Cairo and the delta is known as Lower Egypt.

Somewhat south of Cairo (120 km south, to be exact, about a subject that is not exact), we arrive at the city of Beni Suef, which is a good conventional demarcation point between Lower Egypt and Middle Egypt. Middle Egypt may be said to run to a city on the Nile called Qus, which is 20 km north of Luxor. Upper Egypt starts here and runs south, encompassing Nubia, an area that includes northern Sudan (part of Egypt in ancient times).

Ancient Egyptians thought of their country as having two parts: Upper and Lower Egypt. Their history was said to have begun with the unification of the Two Lands (one of the names for Egypt) when the king of Upper Egypt conquered the north. This duality was reflected in countless ways in Egyptian iconography, most prominently seen in the pharaoh’s Double Crown. The basketlike Red Crown, symbol of the north, would be worn inside the cone-shaped White Crown of the south.

Over time, the north/south duality became part of the multifaceted dialectic that obsessed Egyptian thought: North/south, barren desert/fertile farmland, birth/death were not merely facts of life, but inspired art, ritual, and myth for this imaginative, speculative people.

PREVIOUS PAGE: Howard Carter seated beside the coffin of

King Tutankhamun, removing the consecration oils that covered the

third, or innermost, coffin, 1926. © GRIFFITH INSTITUTE,

UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD

New Year’s Day 1901

Deir el-Bahri, Southern Egypt

EVERYONE WHO WAS ANYONE WAS IN THE DESERT THAT DAY. AN

excited crowd had gathered beneath the stark cliffs that rose dramatically behind the two ancient temples. One was dedicated to the soul of Queen Hatshepsut,

1550 BC

, and the even older one next to it, Mentuhotep I’s, had stood there in the relentless sun for four thousand years.

It was a place of great desolation and silence. Behind the temples towered the lifeless cliffs; and before them, the blinding white sand stretched endlessly to meet the empty sky.

Djeser djeseru

, the ancients called it, the holy of holies, the dwelling place of Meretsinger, the cobra goddess: She Who Loves Silence.

And it was here that the noisy crowd descended, chattering, speculating, filled with the nervous restlessness of modernity. In search of sensation, treasure, beauty—how could the goddess bear them as she watched from her barren heights?

First and foremost was the British viceroy, Lord Cromer, a man whose word was law in Egypt. He’d dropped everything, leaving Cairo in the midst of one of Egypt’s endless crises. After ordering his private train, he’d traveled five hundred miles south, then taken a boat across the Nile, and then a horse-drawn calèche out toward the desert valley. The price of Egyptian cotton had plummeted on the world market, pests were ravaging the crops, and starvation stalked the countryside. But what did that matter next to

the fact that a royal tomb had been discovered? After months of laborious excavation, the diggers had finally reached the door of a burial chamber with its clay seals still intact—and His Lordship wanted to be present at the opening.

As did an assortment of idle princes, pashas, and high-living riffraff from the international moneyed scene … along with the usual hangers-on of the very rich: practitioners of the world’s oldest profession. Which in Egypt didn’t refer to—to what it usually does, but meant grave robbers (or archaeologists, as they are more politely known).

To dig with any success (“to excavate,” in the polite lingo), one needed knowledge. And one needed money—a great deal of it.

Thus, they often came in pairs, the archaeologists and their sugar daddies. There were famous “couples”—inseparables for all their differences of temperament and background. For example, looking back on turn-of-the-century Egyptology, can one think of the American millionaire Theodore Davis apart from the young Cambridge scholar Edward Ayrton?

Together they discovered a long list of tombs and burial shafts, Pharaoh Horemheb’s, Pharaoh Siptah’s, and “the golden tomb” (KV #56)

1*

among them. As well as the mysterious Tomb Kings Valley #55—and the animal tombs (#50, #51, and #52): the mummified and bejeweled pets of Amenhotep II. The beloved creatures

had been stripped of their jewelry by ancient robbers who had even decided to create a “joke”—perhaps the oldest in existence—leaving pharaoh’s monkey and dog face-to-face. Which was how Davis and Ayrton found them some three thousand years later: locked in an eternal stand-off.

The two men, the millionaire and the scholar, made a striking picture: Davis, headstrong, determined, unwilling to be denied anything he wanted. The entrepreneur stood erect, staring down the camera in his flared riding pants and polished boots and gray side whiskers; Ayrton stood next to him, athletic, boyish, shy, a straw boater tilted at a rakish angle as he smiled absentmindedly staring out over the desert. If it wasn’t exactly a marriage made in heaven—the two had their ups and downs—still their partnership produced significant results.

Or take Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon, another such couple. Carter, irascible to the point of being rabid when the fit was on him, intense, brooding, obsessed. With almost no formal education and a humble background, he was the quintessential outsider whose artistic ability was his one saving grace. Where would he have been without his Earl of Carnarvon, the lovable “Porchy”—bon vivant heir to a thirty-six-thousand-acre estate who came to the excavations supplied with fine china, table linen, and the best wines?

Though they tried to pass themselves off as patrons of the arts and archaeology, the truth was that these high rollers were not selfless. They paid for an excavation because they stood to gain a great deal from it, more than they would have at the racetracks and roulette tables of their usual watering holes.