India: A History. Revised and Updated (84 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

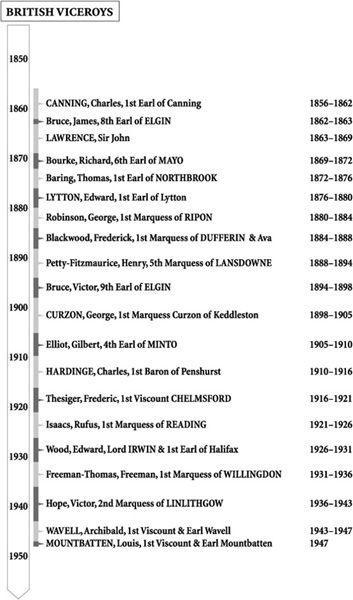

The uncompromising imperialism of a Lytton (1876–80), or the temporising of a Dufferin (1884–8), encouraged such circumventory tactics. Conversely a Liberal viceroy like Lord Ripon (1880–4) was expected to be as sympathetic to Indian demands as was Gladstone to Irish demands, and could therefore expect nationalist support. Yet Ripon, repeatedly thwarted by the caution of the India Office in London and by the opposition of his own officials in India, delivered much less than he promised. He had the pleasure of repealing Lytton’s draconian censorship of the vernacular press, and he introduced a degree of local self-government with the inauguration of municipal and rural boards whose members, partly elected, were to assume responsibility for such things as roads, schools and sewerage. Implementation proved more difficult, especially in Calcutta, Bombay and Madras, where the main deluge of suitably educated Indians met the high dam of greatest official suspicion. Moreover, highly qualified patriots who were exercised about the iniquities of Naoroji’s drain theory found it hard to get excited about actual drains. Yet they liked Ripon’s ideas, they appreciated the need for a political induction which started at the bottom of the ladder, and they eagerly awaited the invitation to climb to the next rung.

This prospect receded in 1883 when the innocuous-looking Ilbert Bill provoked a ‘white backlash’ from India’s British residents. The bill, introduced by the Calcutta government to iron out a minor legal anomaly, was found on close examination to entitle a few Indian barristers who had now risen to the level of district magistrates and session judges to preside over trials of British as well as Indian subjects. This was too much for the planters and businessmen who made up the bulk of the European community. That there had to be Indian judges was one thing, but that an Indian judge might pronounce sentence on a member of the ruling race, perhaps even a female member of the ruling race, provoked the entire community into a hysterical and undisguisedly racist uproar. Memories of Kanpur and the ‘red mutiny’ were resurrected; Ripon was threatened; and, mindful of the ‘indigo’ or ‘blue mutiny’ of 1860, irate loyalists now promised a ‘white mutiny’ which would seal the fate of such a treacherous government. Their campaign ‘gave Indians an object lesson in the arts of unprincipled, but highly organised, agitation’;

8

it was also notably successful, emasculating Ilbert’s bill and discrediting most of Ripon’s other reforms. Here was another British ‘idiom’, another form of ‘discourse’, more raucous than that of the durbar and evidently more potent; it, too, would in due course be emulated.

The histrionics over the Ilbert Bill had come mainly from Bengal, whose British planters, industrialists and traders were much the most numerous. But Bengal also fielded much the largest body of Western-educated and articulate Indians. They rallied to Ripon’s defence and, in loyal support of a cause which for once transcended creed, caste, class and locality, they were joined by fellow activists from all over India. Hailed as ‘a constitutional combination to support the policy of … Government’, this dignified and carefully orchestrated demonstration of all-India support found eloquent expression in the Bombay send-off arranged for Ripon in late 1884.

From Madras and Mysore [reported the

Times of India

], from the Panjab and Gujarat, they came as an organised voice, from the communities where caste and race had merged their differences … waving their banners, rushing along with the carriages, crowding the roofs, and even filling the trees, and cheering their hero to the very echo … in order to express their appreciation of the new principles of government.

9

In December 1885, exactly one year later, also in Bombay, and partly inspired by this demonstration of all-India action, the first Indian National Congress was convened. As yet Congress was just that – a congress, a

gathering; not a movement, let alone a party. It was not unique; another national convention was meeting simultaneously in Calcutta (they would merge in the following year). Nor was it exclusively Indian. Its acknowledged founder, Allan Octavian Hume, was an ex-Secretary for Agriculture in the Calcutta government, a distinguished ornithologist and a Scot. Like his father, a Liberal radical who had spoken ‘longer and oftener and probably worse than any other Member [of the Westminster Parliament]’ in support of every imaginable reform, repeal and abolition, A.O. Hume had long been a thorn in the side of the authority he served. He had been particularly critical of ‘the millions and millions of Indian money’ squandered by Lytton, both on the Imperial Assemblage in Delhi and then on the Second Afghan War which in 1878 climaxed another confused passage of play in the interminable ‘Great Game’ between the British and Russian empires in central Asia.

After Lytton, in the happier times of Ripon’s viceroyalty, Hume had come to see himself as a conduit between Government House and its Indian subjects. The role no doubt appealed to him, as an associate of the Theosophists who from their base in Madras energetically espoused Hindu revivalism while seeking ecstatic encounters with spiritualistic go-betweens; indeed, ‘mystical mahatmas’ seem to have figured prominently amongst Hume’s anonymous Indian informants. There was nothing discreditable in such ‘contacts’. Late Victorians relished spiritual experiments; and in India Theosophy was one of many revivalist movements which were significantly contributing to the climate of social reform and religious and cultural rehabilitation in which national regeneration would flourish.

To the British it seemed that many of these reform movements cancelled one another out. Social reformers who demanded, for instance, an end to child marriages were opposed by religious revivalists who resented any interference with existing custom; in the north, champions of the Hindi language antagonised the heirs of Urdu’s literary heritage; and Marathas invoking the memory of Shivaji to sanction acts of violence were contradicted by universalist movements like the Brahmo Samaj whose adherents stressed the humanity and non-violence of Hinduism. In Bengal, as in Maharashtra, the literary and largely Hindu renaissance often bracketed British rule with that of the Muslim emperors and nawabs which had preceded it, both being deemed equally alien. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee went even further. In his immensely influential novel

Anandamath

(1882), Hindu leaders appeared to be struggling not against the British, who had supposedly come to India as liberators, but against Muslim tyranny and misrule.

10

Needless to say, Muslims took exception to this as to much else about the predominantly Hindu character of many of these movements. In the north they responded both with a burst of fundamentalist activity which appealed to poorer Muslims and with a drive towards a more flexible and outward-looking orthodoxy which could accommodate a degree of Westernisation. The latter trend was well represented by Sir Sayyid Ahmed Khan who in 1875 founded the Anglo-Muhammadan Oriental College, later University, of Aligarh (south-east of Delhi).

All these movements and associations would endow the political struggle with strong spiritual, cultural and social undertones. In the case of Vivekananda, the first of India’s ‘gurus’ to address a world audience, they served to alert international opinion. In the case of the

Arya Samaj

, a reformist and aggressively Hindu ‘Aryan Movement’ which made spectacular advances in the Panjab, they drew on fashions in international scholarship, specifically the pan-Aryan enthusiasms of Max Muller, the Oxford Professor of Sanskrit. Additionally the high-profile Theosophists set a useful organisational example with their annual conventions. But it was the mainstream political groupings of Calcutta, Bombay and Pune, heavily influenced by Dadabhai Naoroji and his associates, which first urged the need for a national congress; the organisation for such a gathering had come into existence at the time of Ripon’s send-off demonstrations in the winter of 1884;

11

and Allan Hume was regarded by the British authorities as the prime instigator. Additionally, by the seventy-two delegates who attended the first Congress, he was seen as an able organiser and, because unaligned as to caste and community, as the most suitable secretary and spokesman.

Hume also had more time and money than most to devote to the Congress. For the next decade it existed as an annual gathering, organised by a local committee in whichever city had been chosen to host it, and presided over by a president chosen for that one occasion. ‘There were no paying members, no permanent organisation, no officials other than a general secretary [usually Hume], no central offices and no funds.’

12

It met over the Christmas break, thereby ensuring that the professional careers of the principally lawyers, journalists and civil servants who attended were not unduly disrupted. Proceedings were conducted in English, the only language shared by all delegates; and given the Congress’s pan-Indian character, resolutions focused on those national, as opposed to local or communal, issues around which delegates could be expected to unite.

Not surprisingly, the first years of Congress would therefore come to be seen as years of caution and moderation. Dufferin would sneer that it

represented only ‘a microscropic minority’. Lord Curzon (viceroy 1899–1905), though conceding that its semi-permanent committees now made it a ‘party’, insisted that it was ‘tottering towards its fall’. Frustration led even supporters to decry the Congress’s ‘mendicancy’ when in the 1890s its ritual demands for political, administrative, and economic concessions, as also its pitiful funds, were re-routed through its London subsidiary. Although Congress continued to aspire to the status of an embryonic Indian parliament, its hopes lay with the Westminster Parliament, with allies in the British Liberal Party, and with the London lobbying of the likes of Dadabhai Naoroji.

An 1892 India Councils Act was accounted a notable Congress triumph. It broadened the remit of the Legislative Councils which advised the viceroy and his provincial governors and to which Indians were already being nominated. It also increased the membership of these councils and conceded that in principle some members might be elected, albeit indirectly. This was a far cry from

swaraj

(self-rule), the avowed objective of many Congress speakers, but it did ensure more Indian representation at the political level. Access to the higher grades of the administration also looked to have been secured when in 1893 the Westminster Parliament acceded to Congress demands for entrance examinations into the elite Indian Civil Service to be held in India as well as England. In the event this measure was aborted by the government in India on the grounds that free and accessible competition would be discriminatory. It would favour, they said, the educated and mainly Hindu elite, so alienating less academic communities like the Muslims and Sikhs of the north-west on whose loyalty the Indian army, and so the British Raj, particularly relied.

Muslim attendances at Congress were already falling away. Hume had assiduously wooed Muslim support but, with his retirement to Britain in 1892, the opposition of Sir Sayyid Ahmed Khan became more pronounced. Anticipating the arguments which would eventually lead to the genesis of Pakistan, Khan insisted that representative government might work in societies ‘united by ties of race, religion, manners, customs, culture and historical traditions [but] in their absence would only injure the well-being and tranquillity of the land.’ The land in question he liked to portray as a bright-eyed bride, one eye being Hindu, the other Muslim, and each equally brilliant. Any cosmetic enhancement which had the effect of favouring one over the other would ruin the whole countenance.

Resentment of Congress, and especially the elitist, ‘mendicant’ and Anglophone tone of its leadership, came also from non-Muslims. In the late 1890s, against a background of industrial unrest, more appalling famines and an outbreak of plague, the first signs of a polarisation in the Congress ranks began to appear in Maharashtra. Moderates who favoured constitutional methods, albeit backed by trenchant economic and political critiques, became identified with Ferozeshah Mehta and Gopal Krishna Gokhale, whose power base was amongst the Bombay intelligentsia. Meanwhile radicals gravitated towards the Marathi populism and the more experimental methods urged by Bal Gangadhar Tilak from his power base around Pune.

Gokhale, a lecturer at Bombay University, and Mehta, a Parsi lawyer, accepted the need for patience and moved easily between the presidency of Congress and membership of the viceroy’s council. Tilak, on the other hand, from the same brahman community which had furnished the Maratha state with its peshwas, experimented with a variety of mass-focus appeals through his editorship of a Marathi newspaper. They included the politicisation of fairs and festivals associated with the local cult of Ganapati (Ganesh) and a patriotic crusade based on the defiance of Shivaji. Tentative boycotts and exhortations to civil disobedience were also tried. In 1897 Tilak’s exposition of Shivaji’s most famous exploit, the disembowelling of the Bijapuri general Afzal Khan with those fearsome steel talons, was taken to have incited the assassination of a British official. Sentenced to prison, Tilak, the scapegoat for this first successful act of terrorism, duly became Tilak, the martyr for the nationalist cause. A repeat performance in 1908 would galvanise all Bombay. Tilak had made the important discovery that the consequences of extremist rhetoric could transcend its appeal.