India Discovered (16 page)

Hidden in the jungle, the great temple complex of Khajuraho (tenth – eleventh centuries AD) was rediscovered in 1838; but not greatly publicized. ‘The sculptor had at times allowed his subject to grow a little warmer than there was any absolute necessity for his doing,’ wrote the first visitor with masterly understatement. Many and ingenious are the explanations which have been advanced for the

mithunas

(love-making groups) and

apsaras

(dancing girls: which cover the walls of almost all the Khajuraho temples.

In attempting the monumental task of classifying India’s architecture, James Fergusson dubbed as ‘Indo-Aryan’ those, mainly north Indian, temples with a curvilinear

sikhara

(tower). The

sikhara

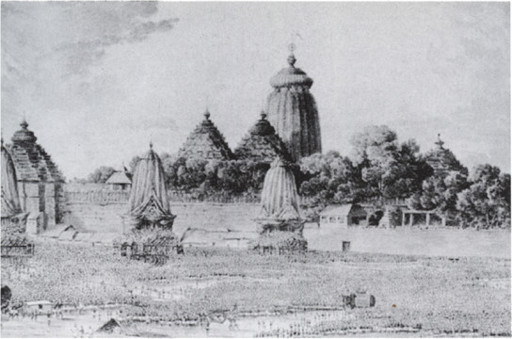

took many forms, his favourite being this pineapple shape typical of Orissa. The festival of Jagannath at Puri was reckoned one of India’s greatest sights. (Drawing by one of Mackenzie’s draughtsmen.)

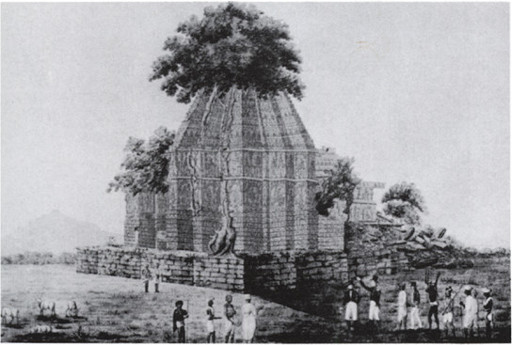

Much of India’s architectural heritage was first brought to notice as a result of the travels of surveyors and map-makers. Colin Mackenzie, India’s first Surveyor-General, encouraged antiquarian research and expected his surveyors, as here, to measure and sketch all buildings of note. (Drawing, possibly a temple at Vijayanagar, by one of Mackenzie’s draughtsmen.)

After spending twenty years

over Taxila, Marshall could hardly be expected to embrace Havell’s damning aesthetic indictment. In Gandhara, as in every other school of art, there was good and bad; there was development, maturity and decline; there was experimentation and imitation. In the panel reliefs the compositions were often exceptional and the figures charming. Craftsmanship was sometimes of the highest order; the Boddhisattva

bust (from Mardan and now in the Peshawar Museum) was superb, ‘the beauty of the chiselling as clear-cut and precise as could be found in any school of sculpture, East or West’. But there was also much that was inferior and insipid. The nice clear expressions and the noble features which so appealed to the previous generation smacked too much of a ‘smarmy prettiness’. Besides, it was now acknowledged

that India had an art of its own that was infinitely more intriguing.

CHAPTER EIGHT

A Little Warmer than Necessary

Included in the list of places Alexander Cunningham submitted to Lord Canning in 1861 as worthy of immediate investigation by the Archaeological Survey, were two sites of outstanding importance for the study of Indian sculpture. The first was Khajuraho, of which notorious place a solitary report had appeared in the Asiatic Society’s journal for 1839.

It had actually been discovered twenty years earlier. Cornet James Franklin, a military surveyor and the brother of the great Arctic explorer, spotted the temples in what was then dense jungle and duly recorded them as ‘ruins’. Unfortunately, Franklin’s handwriting was none too clear: the map makers misread his ‘ruins’ as ‘mines’ and Khajuraho was thought to contain nothing more exciting than old

tin workings. The truth was left for Captain T. S. Burt, one of Prinsep’s roving engineers and the man who had procured the first true facsimiles of the Allahabad column inscriptions. While touring in central India in 1838 he heard tell, from one of the men hired to shoulder his palanquin, ‘of the wonders of this place – Khajroa near Chatpore he called it’. By double marches, or rather rides (the

palanquin bearer must have been regretting his indiscretion), Burt made up the few hours that he thought would suffice for an inspection, and arrived, all unsuspecting, just as the sun was rising above the jungle.

I was much delighted at the venerable and picturesque appearance these several old temples presented as I got within view of them. They reared their sunburnt tops above the trees with all the pride of superior height and age&. My first enquiry, after taking breakfast, was for ancient inscriptions and a temple close by was immediately pointed out as the possessor of one. I went there and sure enough there was an inscription in the No. 3 Sanskrit character of the Allahabad pillar [Kutila]&. It was the largest, the finest, the most legible inscription of any I had yet met with and it was with absolute delight that I set to work to transfer its contents to paper.

A dedicated antiquarian, Burt bent to his task with printer’s ink and wet towels. Like the sportsman who stoops to study a pug mark while, unseen above him, the leopard looks on, he was still blissfully oblivious of what lay in store. He wanted a date and he found it — 1123 in the Samvat era, which meant

AD

1067.

Having done this, I took a look round & and could not help expressing a feeling of wonder at these splendid monuments of antiquity having been erected by a people who have continued to live in such a state of barbarous ignorance. It is a proof that some of these men must then have been of a more superior caste of human being than the rest.

In a moment he was going to regret these words.

Like many of his contemporaries he subscribed to the idea that for centuries Indian culture had been steadily degenerating. At first he thought that in Khajuraho he had found an example of the heights to which it had once aspired. But as he innocently paused to examine the sculptures, he had second thoughts: 1067 must have been well into the period of decline.

I found & seven Hindoo temples, most beautifully and exquisitely carved as to workmanship, but the sculptor had at times allowed his subject to grow a little warmer than there was any absolute necessity for his doing; indeed some of the sculptures here were extremely indecent and offensive, which I was at first much surprised to find in temples that are professed to be erected for good purposes, and on account of religion. But the religion of the ancient Hindoos can not have been very chaste if it induced people under the cloak of religion, to design the most disgraceful representations to desecrate their ecclesiastical erections. The palki [palanquin] bearers, however, appeared to take great delight at those, to them, very agreeable novelties, which they took good care to point out to all present.

Burt must have

been unusually innocent if he was really surprised by the famous

apsaras –

seductive nymphs – and the

mithunas

— the love-making couples (and sometimes quadruples) – of the Khajuraho sculptures. Since the seventeenth century the British had been familiar with the so-called Black Temple of Konarak in Orissa, which boasts similar figures – albeit more blurred by erosion. Near the shore of the Bay

of Bengal, the Black Temple was commonly a landfall for ships making for the Hughli river and Calcutta. As it hove into sight the old India hands would take the young ‘griffins’ aside for whispered innuendos about the sexual mores of the Hindu.

Burt, though, seems to have been genuinely scandalized. Turning in acute embarrassment from his sleeve-tugging bearers, he tried to concentrate on the

architecture. In the Khandariya Mahadeo temple, the noblest of the ‘architectural erections’, he determined to get on the roof to inspect the construction of the soaring pinnacles. The only access was from inside, by shinning up the sacred, and not-so-sacred, images.

From the side wall which was perpendicular I first sent up one of the bearers and then, by laying hold of the leg of one god, and the arm of another, the head of a third and so on, I was luckly enabled, not however without inconvenience, to attain the top of the wall where, on the roof, I found an aperture just large enough for me to creep in at. On entering upon the roof I found that my sole predecessors there for several years before had evidently been the bat and the monkey, and the place for that reason was not the most odoriferous of all places in the world.

Still wary of the

mithunas,

but warming to his subject, Burt toured the whole complex. ‘I shall state my opinion that they are most probably the finest aggregate number of temples congregated together in one place to be met with in all India.’ He described in detail the great bull, Nandi, outside the Visvanatha temple and the even bigger image of Vishnu

in his incarnation as a boar. By his own calculations this statue, a monolith, weighed sixty-eight tons. The female figure representing mankind, and usually borne aloft on the boar’s tusks, was missing. Considering that Burt was surrounded by female figures, his distress at this discovery is surprising. ‘I would willingly have given a hundred rupees [£10] to have had a good sight of her.’

As

he wandered round, penning his thoughts as he went, his style grew increasingly jaunty; he was on the verge of attempting a description of the

mithunas.

But in the end he shied away, contenting himself, before climbing back into his palanquin, with a lively account of another ‘ecclesiastical erection’.

Let us now look at the little Mahadeo, or lingam [the phallus symbol of the god Siva] which is to be seen in another temple. In order to arrive at it, it is necessary to ascend a considerable number of steps, at the top of which is situated the representation of the vital principle. Let us now measure the height of the gentleman. The natives objected to my going inside without taking off my boots, which would have been inconvenient; so standing at the doorway, I saw a bearer measure the height with my walking stick; it amounted to 2⅓ of its height or eight feet and its diameter to 1⅓ or four feet. Its weight will be about 7½ tons & and it is considered by far the biggest lingam in India.

The next account of Khajuraho seems to be Cunningham’s. The General finally arrived there in 1865 and, if rather less naive than Burt, he was certainly not going to be any more explicit; ‘all

of these [the sculptures] are highly indecent and most of them disgustingly obscene’. He must, though, have paid them a bit more attention. On the Khandariya Mahadeo he counted and measured 872 sculptures, mostly two and a half to three feet high. ‘The general effect of this great luxury of embellishment is extremely pleasing although the eye is often distracted by the multiplicity of detail.’

He also agreed with Burt about the date. Studying the script of every visible inscription, he came to the conclusion that all the temples dated from the tenth and eleventh centuries, ‘a date which I should otherwise be inclined to adopt on account of the gross indelicacy of the principal sculptures’. He also ascribed them to the patronage of the Chandel Rajputs of Chatterpore, who were one of the

many rajput clans who so valiantly resisted the Mohammedan invaders.

To Cunningham’s mind it was the fact that Khajuraho had been miraculously preserved from the iconoclastic Mohammedans that constituted its real importance. ‘The remains are more numerous and in better preservation than those of any other ancient city I have seen.’ Hidden away in an extremely remote tract of country, the site

had been deserted by the Chandel rajahs before the Mohammedans advanced; then the jungle quickly smothered it as effectively as did the volcanic lava Pompeii. Though never an especially ancient or sacred site, the magnificence and profusion of its temples, their scarcely credible riot of sculpture and relief, and above all the pristine perfection of every detail, gave some idea of the splendour of

older and holier cities before the Mohammedan conquest.

In the whole of north India there is scarcely a statue that was not defaced by the Islamic invaders, scarcely a temple that was not ravaged. In Delhi the desecration and destruction were total. And the same was true of Mathura, the other site on Cunningham’s list which is of particular relevance to Indian sculpture. Since the discovery of

Stacy’s ‘Silenus’, more carvings had come to light there. ‘In one of the ancient mounds outside the city the remains of a large monastery have lately been discovered. Numerous statues, sculptured pillars and inscribed bases of columns have been brought to light.’ According to Fa Hsien, Mathura had been a thriving Buddhist and Jain centre, and, as the scene of Krishna’s youthful exploits, an important

place of Hindu pilgrimage. Indeed, the latter it still is. But today not a single building in the Mathura area dates back beyond the seventeenth century.

The stupas,

the monasteries, the temples were all razed to the ground by the invaders.